An innovation that launched a family empire

The new millennium has been a strange time for those of us who live in the west. The limitless future at the end of the cold war has been replaced by a sense of middle-aged vulnerability, an uncertainty that many see as a harbinger of a day when other nations will come to dominate the globe in ways that we cannot yet grasp. There is, of course, nothing new under the sun. Some golden ages – think Rome, Constantinople, or Tenochtitlan – have ended abruptly. Other empires – the Spanish, Portuguese and British – have faded gently, but always making way for new life.

The same is true of families, which rise and fall through the generations. One such family were the Wülfing-Lüers, whose members left an indelible mark on the sciences far beyond just chemistry.

The scion of the family, Amatus Lüer, was born in Brunswick in Germany. Apprenticed to a cutler, he showed unusual promise, and set off across Europe to seek his fortune. He eventually landed in Paris in 1834 where he apprenticed brilliantly, but briefly, with the leading Swiss-born surgical instrument maker Joseph-Frédéric-Benoît Charrière. Three years later, Amatus opened the Maison Lüer, on the Place de l’École de Médecine, a few doors down from his mentor.

Medicine was making rapid strides and the increasingly wealthy middle class in Paris was demanding improved and more personal medical treatment.

A superb craftsman, Lüer flourished. He married and his daughter Jeanne joined the business. In 1867 she married Hermann Wülfing, a good prospect who hailed from Barmen in Westphalia. They proved a good team, with Hermann looking after the business side and Jeanne in the workshop, developing new ideas.

Syringes were a growth area. The spectacular effects of snake bites were clear pointers to the fact that direct injection under the skin would be an effective method of drug delivery. Initially, this was done by incision using a scalpel, followed by injection using trocars, or even quills. But soon every manufacturer was developing their own hypodermic syringes, with screw-on needles, and plungers made from leather, metal, or vulcanite – driven by a screw action to deliver precise volumes.

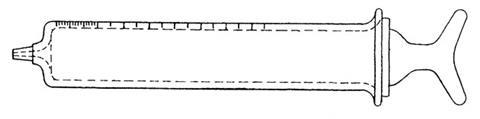

In the late 1860s, the Lüers brought out a calibrated glass and metal syringe, the plunger driven directly rather than by screw action and, crucially, a conical nozzle ground for detachable push-fit needles. But a key issue was sterilisation, essential to prevent infection. According to family legend, it was Jeanne – helped by a glassblower named Fournier – who developed a two piece graduated, all-glass syringe with a tight-fitting ground glass barrel. A minimalist masterpiece, Hermann filed multiple patents to protect the invention.

In a twist of fate, in 1897, the Lüers were visited by two American businessmen, Maxwell Becton and Fairleigh Dickinson, who were travelling in Europe looking for equipment to market. The pair’s first sale back home was a Lüer syringe, which they sold for $2.50 (£1.60). It made their reputation. The following year, they bought exclusive rights to the syringe in North America. The Lüer name was destined for greatness.

The syringe was a huge success. Dickinson, concerned by the dangers of the needles slipping off the nozzle, designed and patented a steel fitting that included the tapered tube at its centre, the needle being locked in place securely by a twist. His Luer-lok would spawn countless additions and variants, including small valves, T-connectors, and vacuum attachments. The Luer-lok and Luer-slip are universal and the original 6° taper now has its own ISO, DIN and EN standards, an astonishing tribute to the reach of such a simple idea.

For the Wülfing-Lüers, business was booming, and they moved to handsome premises on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. The business passed to their son, Guillaume, and then to grandson Paul Roussel. But times were changing.

Becton-Dickinson was only one of a number of big international companies selling mass-produced equipment at competitive prices. It became ever more difficult for the old firm to compete, retreating back to making bespoke devices and eventually acting as a brokerage for imported apparatus. The arrival of internet sales was a death sentence and the firm closed its doors in 1995.

In labs and hospitals across the world, however, the Lüer name lives on. A few days ago I found a small tray laden with forgotten syringes – a little gold mine – at the back of a cupboard, every one of them sporting a Lüer taper. It was a bittersweet find, reminding me of the rise and fall of families. And of empires too.

Andrea Sella (@SellaTheChemist) teaches chemistry at University College London, UK

Thanks to Marie-France Wülfing-Lüer for sharing family photographs and information, and to Philippe Lepine for sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm

References

- H A Wülfing-Lüer, patents: FR242646 (1894) GB3524 (1896); Austrian patent Reg. vol. 45, No. 4186 (1895); US583382 (1897); FR331463 (1903); US772450 (1904)

- F Dickinson, US1742497 (1930); US1793068 (1930)

No comments yet