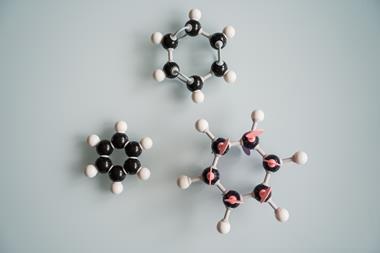

Readers continue celebrating benzene and debating the use of glyphosate

Benzene’s links to dyes and petrol

I loved the benzene issue.

I am old enough to remember UK National Benzole petrol stations. Coal tar benzole was largely a mixture of benzene and toluene, which had a far higher antiknock (octane number) rating than petroleum gasoline, so a 50/50 mixture gave a super fuel. The proportion was reduced as gasoline improved, but it was taken out because of concerns about the health effects of aromatics in about 1960, the antiknock being made up by tetraethyl lead, whose cumulative poisoning had been suppressed by the industry.

William Perkin’s mauve dye actually required p- and o-toluidine as well as aniline. As his aniline was made by nitrating then reducing benzole, the unrecognised minor component toluene was essential, and accounts for its 5% yield based on aniline.

Martin Pitt FRSC

Leeds

Delocalisation differences

In ‘Benzene at 200’, it is claimed that ‘graphene is essentially a sheet of fused benzene rings’. Although I agree that if you were to fuse benzene rings the geometry would be the same as that of graphene, and that both structures would share delocalised π electrons, the delocalisation pattern is different and therefore, it is factually incorrect to claim that.

Mar Jimenez Quesada

Via email

An ode to benzene

I loved Philip Ball’s piece on benzene.

Reminds me of a poem, Benzene, Benzene! Burning bright! (a parody of William Blake’s The Tyger). I wrote it a couple of decades ago, and posted it up online, when it seemed to take on a life of its own, being used as teaching material in the US and India. Indeed, I was even sandwiched between essays of Archimedes and Nehru in the Indian undergraduate textbook Moments from History and Philosophy of Science.

The full poem may now be found in the RSC publication Elementary. It begins:

Benzene! Benzene! Burning bright

Belching engines day and night

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame Kekulé’s symmetry?

Who’d have thought your Carbon Six

Could have produced such toxic tricks

Or provide the building blocks

For a plastic world (and cure the pox)?

Paul Board CChem FRSC

Via email

Continuing the glyphosate debate

I read the article on glyphosate recently. I use glyphosate regularly at home and on the evidence I have seen I intend to continue doing so. The European Chemicals Agency ruled it is safe with no scientific basis for a ban and that is good enough for me.

I think the concerns that have been raised around glyphosate result from the amount of scrutiny it has received. If you do enough studies you will find something just by chance. I also wonder how many of the studies on both humans and the environment reflect real world exposure.

The question then is why has glyphosate received this level of scrutiny? It is very widely used of course but the answer, in my view, is when genetically modified (GM) crops are bred to be herbicide resistant, the herbicide they are bred to be resistant to is usually glyphosate. I suspect much of the pressure to restrict glyphosate originates from anti-GM activism. A complete picture of the issues surrounding glyphosate needs to address this.

Anti-GM activism has little scientific justification and is a purely political issue. In my view, some of the efforts to restrict glyphosate are influenced by this. Tobacco and asbestos were not restricted for a long time despite the evidence being overwhelming that they both caused cancer and other health problems. Is the same thing happening with glyphosate? Not on the basis of the evidence summarised in Chemistry World’s article as far as I can see.

I intend to continue using the product. There are plenty of other total weed killers marketed as glyphosate free available for very little (if any) extra money, but I see no reason to switch.

Does glyphosate affect the wider environment? It might, but the main reason farming affects the environment is it replaces natural ecosystems with a monoculture; it isn’t any chemical input. Organic farming, by requiring more land and consequently more energy to grow the same amount is, if anything, worse. We would be better off producing our food intensively and returning the unused farmland to nature.

Andy Mather MRSC

Leicestershire, UK

Correction

Coal tar is the byproduct of coal distillation, not of gas extraction from crude oil as we incorrectly stated (Chemistry World, July 2025, p24). Thank you to Peter Borrows for bringing this to our attention.

Additional information

No comments yet