Whoever said optical microscopy is not for chemists?

Do you ever regret something you’ve written? Every so often, I write something so inane in this column that later my toes just curl. In last month’s column, devoted to Ernst Ruska’s development of the electron microscope, I made an off-hand remark about how little optical microscopes penetrate into the lives of most chemists. It was only after I’d signed off on the text that I began to realise the silliness of my dismissal. Sure, atoms and molecules, even nanoparticles, are too small to see optically. But microscopes have nevertheless played a central role in the development of chemistry.

The demand for optical equipment after Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s first reports of microscopic ‘animalcules’ resulted in rapid advances in lens technology and in the improvement of the microscope itself. In the winter of 1738–39, the German doctor Nathaniel Lieberkühn presented a couple of microscope designs at meetings of the Royal Society in London. The instrument maker John Cuff, whose workshop was just a few doors away, saw these demonstrations and decided that he could do better. In his design the single lens was mounted on an arm that also held a circular stage onto which samples could be placed. Below this was a circular mirror that could be tilted to reflect light onto the stage itself. The lens could be moved in three dimensions, allowing microorganisms to followed as they swam along.

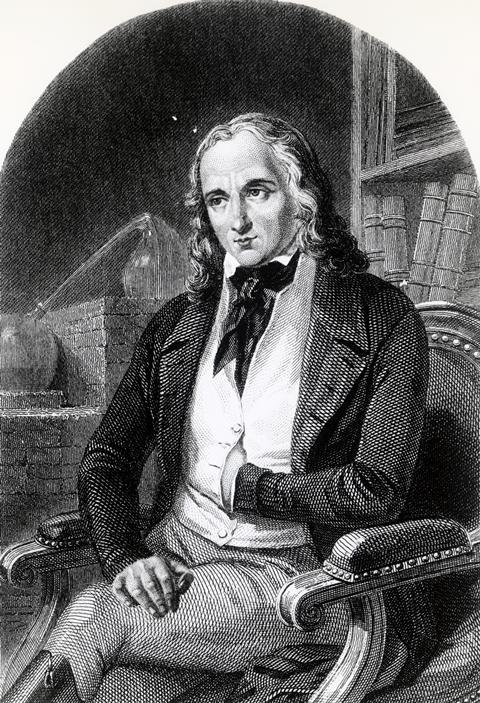

It was Francois-Vincent Raspail who began to use Cuff’s microscope for chemical investigations. Born into a family of pious, royalist innkeepers, he was destined by his parents for the church. Educated first by the local priest who schooled him in various dead languages and a smattering of natural history, he continued his education at the seminary in Avignon only to quit to become the librarian at the school in his home town of Carpentras.

While writing inflammatory pamphlets he began to write about his scientific investigations

In 1815, after the fall of Napoleon, royalist reprisals against suspected supporters of Bonaparte led him to flee to Paris where he had a succession of teaching jobs, which allowed him to study law. It also gave him time to read and think. His interest in politics intensified; he became increasingly republican and joined the carbonari, a secret revolutionary society connected with the freemasons. In this way he met several scientists such as François Arago; while writing inflammatory pamphlets he began to write about his scientific investigations.

For these he commissioned a microscope from the instrument maker Louis-Joseph Deleuil. The pair made significant improvements to Cuff’s design. First, the microscope was housed in a box containing the central brass stand and several accessories, including additional lenses. Once mounted onto the box, the microscope could be focused by means of a rack and pinion movement. The stage could be positioned precisely into position by means of a worm screw. Raspail used lenses made of clear tourmaline, a material with a higher refractive index and lower dispersion than ordinary glass, which reduced the chromatic aberration.

Raspail made an extensive study of grasses, describing over 150 separate species. And he combined his studies of plants with chemistry. He began to use chemical reagents to identify different components of plant tissue. For example, he used iodine to show that starch is confined in specific parts of a plant. Then came methods to identify oils, sugars, crystalline materials and acids and bases within the plant. His investigations made it clear that cells were the fundamental unit of biology and that they showed clear organisation.

Peu de préceptes, beaucoup d’éxemples

His 1830 book on chemical microscopy can be summed up by the quotation at the start: ‘peu de préceptes, beaucoup d’éxemples’ (few rules, many examples). It is a remarkable book: page follows page filled with experiments and observations; the six plates show what a meticulous observer he was. But the introduction hints heavily at his insecurity and his mistrust of authority. The opening pages describe how a young man, ‘victim of the slings and arrows of fortune … seeking to forget men, either to pardon them or to escape the torments of boredom’ might be drawn to science. After fawningly thanking Pierre-Simon Laplace and Claude Louis Berthollet for their influence, he inveighs against older scientists for their conservatism and refusal to accept his discoveries.

The book is all the more remarkable for having been written in prison, his seditious views having finally caught up with him. For the rest of his life he would move between radical republican politics and prison, while touting increasingly cranky tonics, almanacs and miracle cures.

But Raspail’s microscopy and his chemical methods would endure, laying the foundation for histology and the microscale analytical chemistry of Fritz Pregl and Friedrich Emich, as well as for optical mineralogy, crystallography and the study of liquid crystals. And reading between the lines of his book, I don’t suppose that, even in prison, he ever regretted a single word he had written.

No comments yet