Alwyn Davies recounts how five Japanese students and their chemist mentor changed Japanese society forever

Chemists will be familiar with Alexander Williamson’s contribution to chemistry in discovering the Williamson reaction and thereby elucidating the structures of simple organic molecules. Few, however, will be aware of his major contribution to society: playing a leading role in Japan’s conversion from an isolated, industrially backward country to an open one that could join the industrial revolution. It is a remarkable story, and one which deserves to be better known.

In the middle of the 19th century, Japan had lived under the Edo regime for over 200 years. It was a closed, feudal society, where reading foreign literature was a crime, and travel abroad a capital offence. Some enlightened Japanese were aware of the industrial revolution in Europe and realised Japan had to become a more open society and to learn western technology, economics and governance.

In 1863, the Jardine Matheson trading company smuggled five young Samurai students of the Choshu clan – Bunta Inoue, Shunsuke Ito, Yasuke Nomura, Yozo Yamao and Kinsuke Endo – out of Japan, disguised as British sailors, and carried them to England. These young men spoke little or no English and were completely unfamiliar with western ways but wanted to learn enough in just a few years to go back and transform Japanese society. It sounds impossible, yet this is what they did.

A new beginning

At the time, University College London (UCL) was the only university in the UK that accepted applicants irrespective of race, religion, political opinion or background. On the advice of Augustus Prevost, a member of the Council of UCL, Hugh Matheson (of Jardine Matheson) put the group into the care of Williamson, then head of UCL’s chemistry department. Williamson was well suited – his father worked for the East India Company and had connections in the far east, and Williamson had a cosmopolitan background having studied in France and Germany. But above all, Williamson and his wife Catherine were an extremely welcoming couple and they cared for three of the students in their own home.

The group registered on Williamson’s course in analytical chemistry and Catherine Williamson taught them English and helped them to adapt to British society. As well as their studies, Williamson arranged visits to industries such as iron foundries, mines, railways, farms and shipbuilding.

The feelings of these young men are difficult to imagine, coming from a completely different, insular society. It is a great credit to them and to professor and Mrs Williamson that the experiment was so successful.

After the Edo regime was overthrown in 1868 and replaced by the Meiji Restoration, Ito eventually became the first Prime Minister in 1885. He established a cabinet system for government and wrote the constitution. The other students contributed similarly to the restoration of Japan, between them developing finance and commerce, mining, the railways and a system of technical education.

Two years after the original five, a further 15 students followed and were again put in the Williamsons’ charge. They too went on to hold major positions in Japanese government and industry.

Living legacy

The Choshu five created a new era for Japanese society, but their story is also the beginning of Japanese science. When the new, more open Meiji government chose to import western science and technology into the Japanese economy, Williamson was asked to advise on sending teachers from the UK. Those who went included the chemists Robert William Atkinson (who was a pupil of Williamson) and Edward Divers.

Divers became the first professor of natural philosophy at Japan’s Imperial College of Engineering, later principal of the college and professor of inorganic chemistry when the college was incorporated into the University of Tokyo.

Atkinson became the founding professor of chemistry at Daguka Nanko, the forerunner of the University of Tokyo, and published a book on sake production. One of his students, Joji Sakurai, came to work with Williamson in 1876, returning to Japan in 1881 to be a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Tokyo. The next year, at the age of 24, he was appointed professor of chemistry and became the founder of scientific chemistry in Japan, establishing a major school of chemical research. He was several times the president of the Tokyo Chemical Society and established the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research and the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Scientific Research.

In remembrance

Alas, not all members of the original two groups returned safely home. One was claimed by tuberculosis, then rampant in England, with Mrs Williamson nursing him until he died. He was buried in a Buddhist plot in Brookwood cemetery, south of London. Later, two other Japanese students were also buried here. At their request, Alexander and Catherine Williamson were buried in Brookwood when they died, close to their Japanese students.

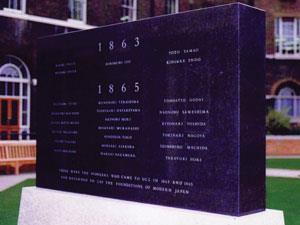

A monument to the Japanese students stands today on the Terrace behind the UCL South Cloisters, and a monument to the Williamsons is being unveiled at Brookwood in July, to mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the Choshu five. It carries the inscription:

Out of the silence

their voices still speak to us

if we but listen

Alwyn Davies is professor emeritus at University College London, UK

No comments yet