Despite hailing from the same pnictogen family, the properties of phosphorus and nitrogen couldn’t be more different. As one of the most ubiquitous gases in nature, nitrogen can readily be isolated as a series of oxides. Diphosphorus (P2), on the other hand, is transient and its oxide relative of N2O4 is highly reactive. Until now this has meant that studying diphosphorus tetroxide was limited to cryogenic temperatures making it an extremely elusive compound.

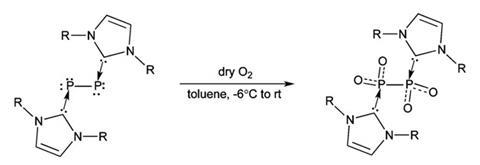

Explaining how they were able to isolate P2O4, team leader Gregory Robinson described their ‘back-door’ approach based on earlier work on carbene-stabilisation of small, highly reactive, main group molecules. Using the organic base N-heterocyclic carbene, the team managed to stabilise the diphosphorus molecule. ‘With carbene-stabilised diphosphorus in hand, we simply utilise molecular oxygen as an oxidant,’ he explains. ‘Stabilised diphosphorus simply splits molecular oxygen yielding a stable molecule containing diphosphorus tetroxide.’

Moreover, on characterising the compound, the results turned out to be something of a surprise. While computation predicts the most energetically favourable structure is an oxo-bridged O2POPO structure, the team found that they had stabilised the less favourable O2P–PO2 isomer instead.

More importantly, they also found the carbene-stabilised diphosphorus tetroxide represents the first example of a phosphorus oxide exhibiting Lewis acid behaviour. ‘The fact that diphosphorus tetroxide can be induced to behave as a Lewis acid further confirms that Lewis bases, such as N-heterocyclic carbenes, are versatile tools that may help chemists access the largely unexplored chemistry of phosphorus oxides, and possibly other main group oxides,’ Robinson adds.

Stephen Liddle, at the University of Nottingham, UK, believes this demonstrates a universal lesson when working with reacting species, as it overturns preconceptions about the possibility of such molecular fractions simply by careful selection of the stabilising species. ‘This is an elegant kinetic trapping technique in which they have made a species that can be isolated under ambient conditions. This means that the synthetic chemist can put it in a jar and do chemistry with it,’ he adds. ‘By inverting the Lewis character, it demonstrates that you never know what new chemistry can come out of it’.

While the question of potential applications remains unanswered, Robinson and his team are continuing to study the reactivity of the molecule. ‘The fact that we have stabilised diphosphorus tetroxide presents interesting synthetic and catalytic possibilities,’ he concludes.

No comments yet