Robin Rogers, and his team at the University of Alabama in the US, had long been interested in using ionic liquids to process cellulose but the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 encouraged them to try something similar with chitin, the structural biopolymer that makes up the shells of various crustaceans. ‘We started working with the Gulf Coast Agricultural and Seafood Co-Op in Bayou La Batre, looking at uses for their shrimp shell waste, about the same time as the moratoriums on shrimping. It was quite clear that new products and profits were needed.’

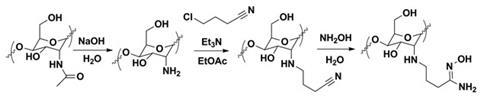

Rogers’ team used ionic liquids to extract long chitin fibres directly from shrimp shells. Chitin is insoluble in most solvents, including water, which allows for the functionalisation of just the surface of the fibres without degrading the bulk strength of the chitin fibre. They converted the surface chitin molecules to a more active form called chitosan and then functionalised it with amidoxime, a functional group with a very high affinity for uranyl ions, and showed the fibre would recover these ions from a dilute aqueous solution.

Nearly all of the uranium in seawater is natural in origin, coming from soluble uranium in the earth’s crust. ‘Imagine the positive environmental potential of reducing or eliminating the need to mine uranium on land, simply by recovering it from the ocean,’ Rogers says.

Jason Love, an extractive metallurgy expert at the University of Edinburgh, in the UK, says the recovery of uranium from seawater, in which it is present in ppb concentrations, would be a valuable alternative to mining for this critical element. ‘While not yet commercialisable due to their brittle nature, the development of these materials is ingenious and represents a significant advance in the use of sustainable chemistry methods to help solve an important global challenge,’ he adds.

Ideally the fibres could be recycled and re-used in the ocean. Another possibility would be to incinerate them to generate energy and leave the metals behind as ash, an idea that could save money and energy by simplifying the recovery process.

Jaime Lizardi Mendoza, who uses chitin in his research at the Center for Food Research and Development in Mexico, says the study will increase the availability of ecologically compatible materials. ‘Chitin is the essential compound that nature has chosen to make many of the most remarkable materials; it is light enough for flying structures, strong enough to be part of the toughest armours, flexible enough to be part of energy release mechanisms, it is also biocompatible and biodegradable. We continue to learn how to use biological polymers, like chitin, to produce innovative materials that help to fulfil our needs whilst respecting the environment.’

References

This paper is free to access until 9th April 2014. Download it here:

P S Barber et al, Green Chem., 2014, DOI: 10.1039/c4gc00092g

No comments yet