Revisiting Darwin's evolutionary insight in the context of modern genetics

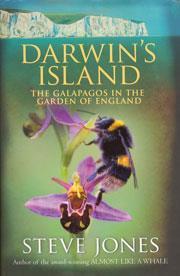

Darwin’s island: the Galapagos in the garden of England

Steve Jones

London, UK: Little, Brown 2009 | 307pp | ?20.00 (HB)

ISBN 978-1408700006

Reviewed by Richard Corfield

In Darwin’s island, Steve Jones builds on his existing reputation for reinterpreting Darwin’s work as he did a few years ago in Almost like a whale: the origin of species updated. It is a clever idea because it enables him to marry genetics - a subject about which Darwin knew nothing - with evolutionary theory, a subject about which Darwin knew rather a lot.

It was the work of the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel that established genetics and provided an explanation of the underlying mechanism by which Darwin’s theory of natural selection could operate.

Although Darwin himself was not aware of Mendel’s work, the 20th century certainly saw an explosion in the importance of genetics as evidenced by Watson and Crick’s epochal discovery of the structure of DNA in 1952 through to the discovery of lateral gene transfer (acquisition of genetic material laterally through ’infection’ rather than vertically through reproduction) only a few years ago. So it is certainly appropriate to revisit the many aspects of Darwin’s original insight as well as his later work in the context of modern genetics.

In Darwin’s island Jones reiterates the point that Darwin’s achievement was not solely confined to what he did during his much celebrated voyage aboard HMS Beagle. When he got home to Down House in Kent he spent the rest of his life working on the implications of his theory and writing a whole host of other books which founded many other biological disciplines. The other books are important because they show how Darwin was working out the ramifications of his insight; that more organisms are born than can possibly survive and these - by definition the ’fittest’ - will live to pass on their genetic material.

In Darwin’s island Jones’ point is that Darwin himself was aware of the way his theory of evolution by natural selection sits at the very heart of biology. The book also illustrates that Darwin had no need to go back to the Galapagos to perform more fieldwork to flesh out his theory. If natural selection is correct then the principles apply just as soundly in the Garden of England as they do on a cluster of remote Pacific atolls. Darwin knew that.

Jones’ book is a delight and will be of value to all those interested in the history of science.

No comments yet