For Frank Leibfarth, focussing on reactivity and selectivity helps him bridge the gap between fundamental and applied research

‘There’s a lot of groups who develop new chemistry, who struggle to know exactly what application it will be best for. And there’s a lot of groups working on important problems without fundamental innovations on the reactivity or selectivity front,’ says Frank Leibfarth. But he thrives on both fronts.

Leibfarth’s philosophy is to use and develop synthetic chemistry to tackle societal challenges with simplicity. This approach has resulted in new ways to upcycle plastics and remove PFAS from drinking water.

He credits a slightly unconventional training route for helping him operate at the intersection of fundamental and applied polymer chemistry so effectively. He earned a PhD in polymer chemistry, then moved – against his PhD advisor’s recommendation – into an organic chemistry postdoc. ‘Organic chemistry, as you may know, is a very intimidating field full of traditionally very big personalities. To step in as an outsider was a big leap.’

Today he runs a group of around 20 people at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a clear mission: ‘We want to be one of the best polymer chemistry groups internationally.’ Supporting that mission is what Leibfarth calls the lab’s ‘special sauce’: the way they pursue reactivity. ‘We look at reactivity, usually in medicinal chemistry or older physical organic literature, and think how that could make an impact in polymer science,’ he says.

That approach works because the group is intentionally interdisciplinary. It develops new catalysts but is also ‘darn good’ at characterising new materials. ‘If a material has a certain property, we know the application it fits, what matters in that application, and how to tune the material to get there,’ he explains.

From trash to treasure

A key focus of the Leibfarth group’s research is polymer upcycling. For example, they’ve developed a general strategy to functionalise aliphatic C(sp³)–H bonds, which can create elastomers with the tensile properties of polyolefin ionomers from postconsumer plastic waste.

The process was inspired by the way medicinal chemists apply late-stage functionalisation to drug-like molecules and uses a shelf-stable O-alkenylhydroxamate reagent that, under mild heating or visible light, generates nitrogen-centred radicals.1 These radicals abstract hydrogen from aliphatic C–H bonds to form carbon radicals that then react with an external trapping agent, allowing diverse functional groups to be installed, such as carboxylates to make polyolefin ionomers or enamines to make reprocessable polymer networks. The team demonstrated this approach by converting postconsumer polyethylene foam into polyolefin ionomers. Notably, the process works in a reactive extruder without any solvent – a technique widely used to manufacture other polymers.

We want to be one of the best polymer chemistry groups internationally

‘I think that’s a very clear example of upcycling … it’s a direct way to turn something without value into something considerably more valuable,’ says Leibfarth.

But while the reagent can successfully introduce new functional groups without degrading the parent polymer, which has previously been a limitation in the field, Leibfarth is upfront that it’s currently too costly and required at impractically high loadings. ‘Those are things we’re definitely working on,’ he says.

Another strand of the group’s upcycling work focuses on turning waste polyolefins into vitrimers – materials that combine the durability of crosslinked polymers with the reprocessability of thermoplastics.2 Traditionally, vitrimers are made by mixing and curing specialty monomers, but Leibfarth’s group can make them by using C–H functionalisation to add crosslinking groups to polyethylene and polypropylene. Unlike conventional vitrimers, which often creep over time, these materials resist deformation thanks to crosslinks organised into discrete domains separated by crystalline regions.

Targeting PFAS

Leibfarth is also known for his work developing adsorbents to remove PFAS from drinking water. That began after a representative from the state government attended a faculty meeting, ‘which rarely happens, as you can imagine’, to say PFAS levels 70 times above new regulatory limits had been detected in the Cape Fear River – a major local drinking water source. They asked for ideas to remove these forever chemicals and Leibfarth had one.3 It combined two concepts – ion exchange and fluorophilicity – to give a resin that could selectively pull PFAS out of water. It led to him and his colleague, environmental engineer Orlando Coronell, being allocated $10 million from the state to fund a centre to scale up and test new materials at real treatment plants.

But scaling up meant rethinking everything. The original resin cost up to $1000 (£743) per kilogram and was made from fluorinated compounds that raised environmental concerns of their own. So Leibfarth and Coronell pivoted to common, inexpensive monomers – though the details remain proprietary information.

In year-long pilot tests at four municipal water treatment plants, the new resin removed short-chain PFAS for three times longer than activated carbon and 40% longer than the best commercial ion-exchange resins without releasing trapped PFAS back into the water, which is a flaw in existing systems.

To bring this technology to market, Leibfarth co-founded Sorbenta with Coronell, which licensed the IP and is scaling production from kilograms to tonnes while working with utility companies to test real-world water sources.

Science that serves

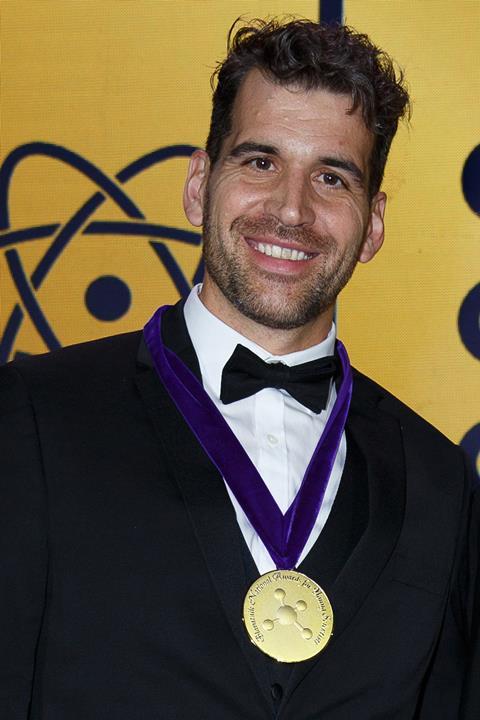

Leibfarth’s PFAS removal and plastic upcycling work saw him named the chemical science laureate at the 2025 Blavatnik National Awards for Young Scientists in the US. He describes his journey to this point as surreal. ‘My mom was a nurse, my dad drove a semi … But luckily through education I was offered lots of wonderful opportunities, and I feel like I took advantage of them. When I got this job, I was so excited to have a thing I got to do every day that I also enjoyed.’

‘I am proud to have done this at a public university, especially with my PFAS work. I recognise our obligation to the people of the state who give us a lot of our funding and to do research that has a direct impact on my community, but also be recognised internationally for it, is something that I’m really proud of.’

References

1 T J Fazekas et al, Science, 2022, 375, 545 (DOI: 10.1126/science.abh4308)

2 E K Neidhart et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2023, 145, 27450 (DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c08682)

3 E Kumarasamy et al, ACS Cent. Sci., 2020, 6, 487 (DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b01224)

No comments yet