Frances Arnold’s masterful retraction highlights the problems with publication-driven science

Retracting a paper, especially if you are a high-profile researcher, is never going to be painless. But the biggest fear may be that it will blemish your reputation, invite accusations of hubris, and create wariness about other claims you have made or will make.

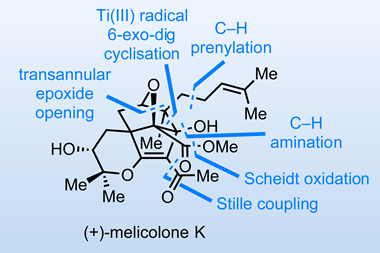

Yet the response to a retraction by Caltech chemical engineer Frances Arnold, whose profile as 2018 chemistry Nobel laureate could hardly be higher, has been very different: it has been universally, and rightly, praised as a model of integrity and responsibility. In a tweet following up on the announcement of the retraction of her group’s paper in Science in May of last year on the enzymatic synthesis of beta-lactams, she said: ‘I apologize to all. I was a bit busy when this was submitted, and did not do my job well.’

It is painful to admit, but important to do so. I apologize to all. I was a bit busy when this was submitted, and did not do my job well. https://t.co/gJDU0pzlN8

— Frances Arnold (@francesarnold) January 2, 2020

What’s so admirable in this statement is precisely what is too often lacking now in public apologies – in science, yes, but even more so in public life generally. The apology is simple and direct, and explains without making excuses. It would be nice, though forlorn, to think that politicians might take a lesson here: saying sorry well enhances rather than diminishes your reputation and credibility.

Yet the response to a retraction by Caltech chemical engineer Frances Arnold, whose profile as 2018 chemistry Nobel laureate could hardly be higher, has been very different: it has been universally, and rightly, praised as a model of integrity and responsibility. In a tweet following up on the announcement of the retraction of her group’s paper in Science in May of last year on the enzymatic synthesis of beta-lactams, she said: ‘I apologize to all. I was a bit busy when this was submitted, and did not do my job well.’

What’s so admirable in this statement is precisely what is too often lacking now in public apologies – in science, yes, but even more so in public life generally. The apology is simple and direct, and explains without making excuses. It would be nice, though forlorn, to think that politicians might take a lesson here: saying sorry well enhances rather than diminishes your reputation and credibility.

Too much to wait?

There is another lesson to be learnt, however. The demands of running an ambitious research group while acting as a spokesperson for science – and, in Arnold’s case, also being on the board of directors of Alphabet, Google’s parent company – must be fearsome. But as Arnold’s statement implies, problems like this often arise because we are trying to do too much too quickly. The problems with this work came to light when the group was unable to reproduce the published results, leading to the discovery that key details and data were missing from the lab notebook of the first author. There is nothing unusual about such follow-up studies being deferred until after publication – but wouldn’t it be better if the norm was to wait until findings have been thoroughly checked and replicated before announcing them?

The obvious response is: better for whom? Any researcher who delays publication until every wrinkle has been smoothed and every claim triple-checked is never going to come first in a competitive field. Is it fair to expect them to sacrifice priority for the public good of publishing work that has been verified beyond all reasonable doubt? They might then forego the chance of a high-impact paper, with consequences for their own performance metrics.

In short, the problem is systemic: science is often in too much of a hurry, for reasons that are understandable but not beneficial to science itself. With this in mind, developmental psychologist Uta Frith of University College London, inspired by the Slow Food initiative, recently called for a Slow Science movement. ‘For me the key concept in both Slow Food and Slow Science is not slowing down the fast pace of life for its own sake, but quality,’ she says.

Slow but sure

As she discovered, it’s not a new idea. A manifesto was presented by the Berlin-based Slow Science Academy in 2010 that said: ‘Science needs time to think. Science needs time to read, and time to fail.’ As that document pointed out, pretty much all science used to be ‘slow science’, because there was little alternative. Famously, Isaac Newton, Henry Cavendish and Charles Darwin had to be positively begged or cajoled to publish their immensely important work. (In the cases of Newton and Darwin, an element of competition did the trick – honourably so with Darwin, who didn’t want to lose priority to Alfred Russel Wallace but didn’t try to beat him into print either. The impetus behind Newton’s Principia was instead the bitter wish to trump Robert Hooke’s rash claims about planetary orbits.)

Frith points out the familiar perils of a rush to publish: quantity becomes more important than quality; papers are judged by journal impact factors, not actual citations; retractions become necessary because not enough checks were applied; and so on. A demand for fast science, she says, may also penalise those (such as young researchers and women) who take time out for good reason, and people with disabilities such as visual impairment or dyslexia, who may need to take more time over their work. Ultimately, retractions and irreproducibility undermine the public credibility of science itself.

The factors driving fast science are well known too: the publish-or-perish culture, perverse incentives created by current metrics and output-based assessment, the squeezing of funding opportunities, the increasing commercial interests in science (and focus on patent priority), the way email has speeded up working life… All this is often lamented, but creating a unified banner of Slow Science under which resistance might be coordinated could be a way forward.

Many researchers will doubtless have read Arnold’s statement with a feeling of ‘there but for the grace of God…’ But it’s not God’s decision; it’s yours.

No comments yet