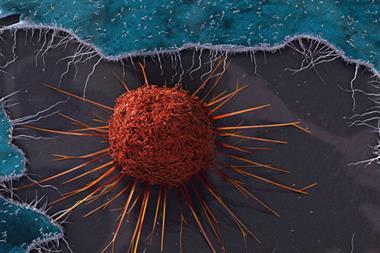

Immuno-oncological drugs look set to earn billions and significantly lengthen patients’ lives

Drug firms are investing heavily in clinical trials and collaborations as they seek to capitalise on the potential of cancer therapies that enlist or enhance our immune systems’ ability to fight tumours. The most optimistic estimates say immuno-oncology drugs could be worth up to $35 billion (£21 billion) a year over the next decade. A host of companies are chasing this prize, and unleashed a flood of clinical trial data at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting held in Chicago in early June.

Checkpoint inhibitors are a subset of immuno-oncological drugs garnering a lot of attention. The name refers to the way some tumour cells activate ‘checkpoint receptors’ that allow them to evade detection and destruction by our immune systems. The tumour cells produce proteins that healthy tissues normally use to tell T-cell lymphocytes to back off, leaving them free to continue multiplying and spreading.

Several pharmaceutical companies are trying to intervene in this stand-off with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Some target checkpoint receptors – specifically the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 (PD1) receptors. An early sign of the approach’s potential came in 2011, when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS)’s CTLA-4 inhibitor Yervoy (ipilimumab) metastatic melanoma treatment.

Since then Merck & Co’s anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab has become the star of its new drug pipeline, also focusing initially on melanoma. At ASCO, Merck revealed that in its Phase Ib trial of pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma, 69% of patients were still alive after one year. The FDA has given pembrolizumab its ‘breakthrough’ label, reserved for drugs for serious or life-threatening diseases that promise substantial improvements over existing therapies. While that means the FDA must decide whether to approve its use in advanced melanoma by 28 October, Merck now also has studies ongoing in more than 30 cancers.

But BMS is also racing to be the first to market with its own anti-PD1 antibody, nivolumab, which has delivered impressive early results in combination with Yervoy. In another Phase Ib trial whose results were announced at ASCO, 94% of advanced melanoma patients taking the drugs survived for a year, and 88% survived for two years. On a conference call with investors, Michael Giordano (head of development in oncology and immunology at BMS) compared that situation against what advanced melanoma patients could have expected before Yervoy. ‘If we were lucky, one in 10 [was] alive at the end of one or two years,’ he said. BMS’ nivolumab has FDA breakthrough status for Hodgkin lymphoma, and slightly lower priority ‘fast track’ status on melanoma and two other cancers.

Stripping cancer bare

Roche and AstraZeneca (AZ), meanwhile, are targeting the PD-L1 ligand protein that sends the ‘back off’ signal to its PD1 partner. At ASCO Roche unveiled phase I results for its anti-PD-L1 mAb, MPDL3280A, in bladder cancer, which have enabled it to gain breakthrough status for this disease. And not only is AZ accelerating its anti-PD-L1 mAb MEDI4736 into Phase III trials, it’s combining it with its pipeline anti-CTLA-4 mAb tremelimumab, which it has licensed from Pfizer. Because the company thinks such combinations will be especially powerful, it is also developing an anti-PD1 antibody, explained Ed Bradley, head of innovative medicines oncology at AZ subsidiary MedImmune.

‘Monotherapy is great, but all of the preclinical biology shows that combinations are much more likely to be effective,’ Bradley told a briefing for analyst and investors. ‘You’ll see enormous progress and activity in moving to combinations that take advantage of these components of the immune system. This is where we think the major advances are going to come in cancer therapy.’

This philosophy has seen Merck, AZ and BMS all set up clinical trial collaborations pairing their anti-PD-L1/PD1 antibodies with Incyte’s indoleamine dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) inhibitor INCB24360. IDO-1 is an enzyme that gives tumour cells another way to dampen our immune system, and Incyte says pre-clinical tests show inhibiting it is ‘synergistic’ with checkpoint inhibition. Significantly, BMS also partnered with monoclonal antibody developer CytomX in late May to work on four immuno-oncology targets, including CTLA-4. After a $50 million up-front payment, CytomX could earn up to $298 million in milestone payments for each target.

T-cell engineering is an earlier-stage immuno-oncological technology, in which patients’ own immune cells are extracted, enhanced and then given back to them. Though GSK recently sold its cancer drugs portfolio to Novartis, on 2 June it announced a $350 million deal to take Adaptimmune’s T-cell receptor (TCR) engineering technology through clinical trials. Adaptimmune’s approach differs from existing antigen receptor transplant methods, exploited by Novartis and several smaller firms, which add chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) antibody fragments to the surface of T-cells extracted from patients. Instead, Adaptimmune introduces a gene encoding new TCRs to patients’ T-cells, which it says means it can target a wider range of proteins.

No comments yet