The ancient tradition of bread baking depends on a cascade of chemical reactions. Scientists have found myriad ways to modify the process, say Bryan Reuben and Tom Coultate

The usually quiet world of bread has been disturbed recently by both economic and technological changes. Wild fluctuations in the price of wheat in the past two years have made life difficult for the milling and baking industries and, at one point, the percentage increase in price of bread in the UK was greater than at any time since deregulation in the 1950s. The credit crunch has pushed people towards bread as a replacement for more expensive foods - in the UK, the annual quantity of bread sold up to April 2009 showed the first increase for 35 years.

The traditional English preference for white bread has led to at least two centuries of the use of additives, or adulterants, depending on your point of view. Initially this was to cheapen bread, enabling it to appear white in spite of the inclusion of potatoes, oats or worse. In more recent decades, the goal has been a soft, springy and open crumb structure, even with the non-ideal, protein-poor wheat that is grown in Europe.

Protein is a key constituent of the wheat flour used for bread production. An essential component of the baked bread’s final structure, it is a favourite target for scientists looking to intervene in the baking process. Flour used for most modern bread-making in the UK contains at least 12 per cent protein, almost all of this the so-called gluten proteins that would provide nitrogen for the growth of the germinating wheat seedling.

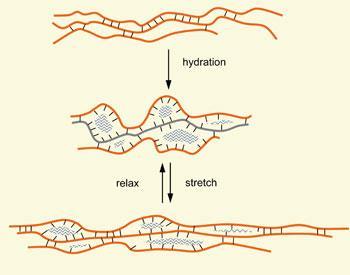

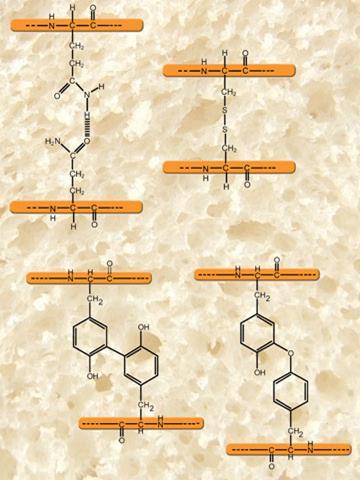

As the baker mixes flour with water at the start of the bread-making process, these proteins hydrate to form gluten, a viscoelastic matrix holding the starch granules that constitute the bulk of flour. Gluten is not a single molecular protein species but a mixture of water-insoluble proteins falling into two broad classes, the gliadins and the glutenins.1,2 A typical wheat variety may have as many as 40 different gliadins, whose molecular weights fall between 28,000 and 55,000. In contrast, the glutenins are multi-protein macro-polymers whose overall molecular weights may exceed 2 million. As their insolubility suggests, all the gluten proteins are dominated by hydrophobic amino acids, particularly glutamine. This amide-bearing amino acid has a strong tendency to form hydrogen bonds between protein strands - a major factor in the physical structure and behaviour of gluten. In addition, the glutenin protein chains of the subunits contain thiol groups from the amino acid cysteine, which form disulfide bridges that hold the glutenin macro-polymer and the gluten complex together.2 Recent research suggests that cross links are also formed between the tyrosine residues in the gluten. Like the disulfide bridges, their formation is catalysed by oxidising agents.3,4,5

Dough in no time

The hydration of flour to give dough is not just a simple mixing process; much mechanical work is also needed, initially applied by the mixer and then by expanding CO2 bubbles within the dough. These bubbles form as yeast ferment the sugars liberated from hydrated starch granules by the flour’s natural complement of amylase enzymes. Mechanical work stretches the gluten into sheets that trap the CO2 - as the dough expands, the gluten molecules uncoil and reveal far more inter-molecular hydrogen bonding opportunities, and the dough becomes stronger.

For the dough to stretch, the disulfide bridges holding the glutenin components together must repeatedly cleave and reform as the protein chains slide over each other. These exchange reactions require the participation of oxidising-reducing systems, whose components occur naturally in flour. This is the point at which the chemists have, wittingly or unwittingly, often intervened.

The traditional breadmaking process has a serious drawback. After mixing, the dough must be left to prove for at least three hours for the bubble expansion to develop the gluten. The dough is then ’knocked back’ to remove most of the CO2 - a process usually combined with scaling (ie getting the dough into the right size chunks) and moulding to fit the tin - before being allowed to prove a second time before it goes into the oven. Although this long fermentation develops flavour, it is costly in time, with bakers having to rise early in the morning to produce fresh bread for the day. In addition, the mounds of fermenting dough take up expensive floor space and present hygiene problems. Research efforts were therefore directed to developing a ’no time’ dough: by increasing the amount of yeast; by mixing vigorously to increase the rate of bubble formation; and by adding oxidising agents to promote disulfide bond formation.

Azodicarbonamide, potassium iodate and potassium bromate have been used as oxidising agents, bromate being the most cost-effective. It was preferred in the Do-Maker process (developed in the US) and in early versions of the Chorleywood bread process (CBP), which was developed in the UK by the Flour Milling and Baking Research Association in the early 1960s and which featured powerful mechanical stirring to incorporate bubbles. Even though bromate was permitted at the time, and was in any case decomposed to bromide at baking temperatures, it was under suspicion as a carcinogen and was banned in the UK in 1990, although not in the US. Bromate’s ban was facilitated by the development of bread-making processes dependant on the use of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). Ascorbic acid is, of course, a reducing agent but, during dough mixing, the enzyme ascorbic acid oxidase, naturally present in flour, catalyses its conversion to its oxidising form, dehydroascorbic acid (DHAA). In a reaction catalysed by another flour enzyme, DHAA converts glutathione (GSH), a tripeptide naturally found in wheat flour, to its dimer (GSSG). GSH, but not GSSG, can form disulfide bonds - so removing GSH prevents it from disrupting the disulfide crosslinking that otherwise form between gluten proteins.

The CBP, which still dominates the UK bread market and has also been adopted in other countries including South Africa and Australia, required large, powerful and expensive mixers, and the smaller bakers required something less elaborate, leading to the development of the activated dough development (ADD) process. This still used potassium bromate and ascorbic acid as the oxidising agents, but l-cysteine was added as a rapid-acting reducing agent, which aided the fission and reformation of disulfide linkages, easing the expansion of the dough. Extra water was added to compensate for lack of natural softening, plus extra yeast to maintain normal proving times, and the resulting process could be used by small bakers with inexpensive mixers. Bizarrely, until Japanese food company Ajinomoto commercialised a chemical route in 2001, l-cysteine was still manufactured from human hair. The ADD process provided 18 years of baking happiness until the banning of bromate in the UK in 1990 sent the industry back to the drawing board.

Enzyme assistance

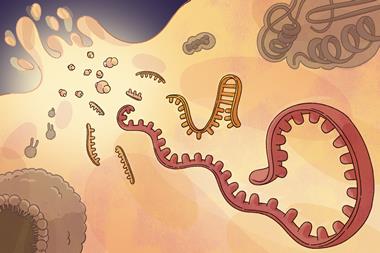

The difficulties with chemical additives reawakened interest in the use of enzyme supplements.6 Flour naturally contains both alpha- and beta-amylases, which between them break down some of the starch in the dough to the fermentable sugars, maltose and glucose. By artificially increasing the level of amylases in the dough, the quantities of these sugars available for the yeast fermentation can be enhanced, accelerating the production of CO2 - and of ethanol, the other glucose fermentation product, which is a major contributor to the aroma of baking bread. Choice of amylases is crucial. The bacterial amylases widely used in the manufacture of glucose syrups are unsuitable as they are heat stable - they would survive the baking temperatures and go on to generate sticky dextrins that would, in a few hours, reduce the centre of a loaf to a glutinous mess.

The added enzymes have similar properties to those naturally occurring in dough and are destroyed in the baking process. Consequently, in 1996, the use of enzymes in bread was totally deregulated, to the horror of the anti-additive lobby. Their use has proved an attractive alternative to the CBP.

Proteases are enzymes that cleave the peptide bond in proteins. In bread making, they decrease mixing times by increasing the speed of water absorption, increasing dough extensibility and reducing dough consistency. They also produce small quantities of amino acids from the proteins in gluten, which interact via a Maillard reaction with glucose, to give flavour components and crust colour. These processes are slow and are the reason why artisan bread has more flavour then ’no-time’ breads. More than 300 flavour compounds have been identified.7

On the shelf

As most people will have inadvertently discovered, bread kept too long goes stale. This process can be slowed by adding fats to the dough. Initially the linear amylose polymers in flour - about one fifth of the total starch - are aligned, side by side, in a microcrystalline structure. This structure is destroyed during baking, but subsequently crystallisation recommences, to a crystal form which contains lots of water of hydration. This reduces the amount of ’free’ water in the bread, and it loses ’springiness’ and appears to dry out. Adding fats to the dough, which are hydrophobic, slows the migration of water during the crystallisation, keeping the bread moist. They also improve loaf volume and crumb softness.

Animal fats and fish oils were used in the past, but modern baking processes demand a solid fat - HPKO (hardened or partly hydrogenated palm kernel oil) is currently widely used, but palm oil cultivation is destroying the habitat of the orang-utan, and palm oil is increasingly sought after as a potential source of biofuel. One possible alternative is to use the higher melting compounds from vegetable oils, which are extracted by cooling the oil until they crystallise out.

Polar lipids with hydrophobic side chains are also used as anti-staling agents.7 Their polar components interact with the surface of amylopectin molecules but, in so doing, their non-polar fatty acid chains provide a degree of ’waterproofing’. They act, apparently, by binding to gluten proteins. Modern wholemeal bread depends crucially on anti-staling agents for its palatability.

Salt is always added to dough - and not just for the taste. Its ions shield gluten’s charges from one another and enable the protein molecules to approach more closely, giving a stronger and more stable dough.7 Governments are often anxious to reduce salt levels in the diet, but there is a limit as to how far this can be carried with bread. In

the absence of salt, dough is sticky, and the resulting bread is unpalatable.

There is little doubt that slowly fermented dough gives a more flavoursome bread than no-time doughs. Nonetheless, CBP bread has many advantages for consumers. It is soft, stales only slowly, and makes good toast and sandwiches. It can use low protein European flour and, indeed, this was the spur to the development of CBP in the first place. It is also cheap compared with the sophisticated ethnic breads and so-called morning goods (such as rolls and croissants) currently occupying the top end of the market. It has gained at their expense during the past year.

Bryan Reuben is the co-author of Bread: a slice of history. Stroud, UK: The History Press, 2009

Tom Coultate is the author of Food: the chemistry of its components. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing, 2009

Both authors are associated with London South Bank University.

References

1 M Donovan, Domestic economy, 1830, London, UK: Longman

2 H Wieser, Food Microbiol., 2007, 24, 115 (DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.004)

3 K A Tilley et al, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2001, 49, 2627 (DOI: 10.1021/jf010113h)

4 E Peña et al, J. Cereal Sci., 2006, 44, 144 (DOI: 10.1016/j.jcs.2006.05.003)

5 A Rodriguez-Mateos et al, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2006, 54, 2761 (DOI: 10.1021/jf052933q)

6 H Goesaert et al, in Bakery products, ed. Y H Hui. 2006, Oxford, UK: Blackwell

7 E Buehler, Bread science, 2006, Carrboro NC, US: Two Blue Books

No comments yet