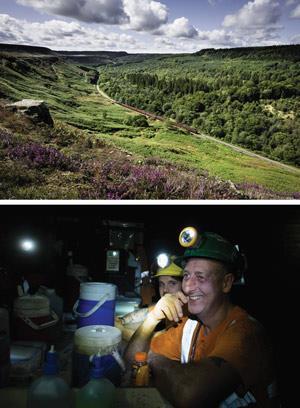

A new mine could produce up to 20 million tonnes of potash each year and provide 1000 jobs – but it’s in a national park. Michael Freemantle reports

Export of polyhalite, a high grade form of potash, mined from a deposit beneath the North York Moors National Park could reduce the United Kingdom’s trade deficit by 4%. That is according to studies conducted for Sirius Minerals, the UK-based fertiliser development company planning to construct the mine. The company predicts that when the mine is fully operational it will contribute £1 billion annually to the country’s gross domestic product. In addition, the York Potash Project, as it is known, will create over 1000 jobs and many more in the supply chain. The company envisages that the project will ‘secure a supply of high value potash for generations to come’.

The project will involve the construction of a 37.5km underground mineral transport system to convey the potash extracted from the mine near Whitby to a materials handling facility located on Teesside at the Wilton International site in Redcar. The facility will crush and granulate the potash and a conveyer system will link it to a new quay adjacent to Teesport.

The harbour facilities will lie next to the Redcar iron and steel works formerly owned by Sahaviriya Steel Industries (SSI). The development of the new potash facilities on Teesside should be good news to some of SSI’s employees: last September, SSI announced that it was winding up its UK business and laying off its 2000-strong workforce owing to the deterioration of steel prices throughout the world during 2015.

In October last year, Sirius Minerals received final decision notices formally granting planning permission to develop the mine, mineral transport system, and materials handling facility. ‘The only outstanding permission is for the development of the harbour facilities at Teesside,’ says Gareth Edmunds, Director of External Affairs at Sirius Minerals.

The development of these facilities is regarded as a nationally significant infrastructure project. York Potash was therefore required to apply to the Planning Inspectorate for England and Wales to get consent to develop the facilities. The company submitted their application in March 2015. A decision is due to be made in the summer this year.

Existing mines

At present, the only potash mine in the UK is run by Cleveland Potash, a subsidiary of ICL Fertilizers which in turn is a division of Israel Chemicals Limited, headquartered in Tel Aviv. The British mine is located near the village of Boulby on the north-east coast of the North York Moors. ICL Fertilizers also produces potash in Israel at its Dead Sea Works and from two mines in Catalonia, Spain, operated by Iberpotash, another of the division’s subsidiaries. Overall, ICL Fertilizers, through its subsidiaries, accounts for over 10% of global potash production.

Boulby Mine has a seam of sylvinite ore averaging seven metres in thickness at depths between 1100 metres and 1400 metres. The ore was deposited more than 225 million years ago when ancient seas evaporated. Some of the mined ore, after crushing and sieving, is sold as a soil fertilizer for crops – such as sugar beet, spinach, and carrots – that benefit from the application of sodium as well as potassium.

The sylvinite ore consists of 45% to 55% halite (salt), 35% to 45% sylvite (potash), and small amounts of impurities such as traces of iron oxide that colour the ore red. A refinery on the site separates the salt from the potash and removes the impurities. The salt is sold primarily for de-icing British roads in the winter.

Cleveland Potash produces various grades of potash for use as fertilisers or for industrial applications (see box). The fertiliser industry usually expresses the potassium content of potash notionally as potassium oxide, K2O, which is somewhat strange as potassium chloride, the most common form of potash, does not contain oxygen. For example, Cleveland Potash supplies standard grade potash (KCl) with a nutrient composition of 61% K2O and 46% chloride (Cl). The company also produces a range of compound fertilisers, notably NPK fertilisers that contain all three primary macronutrients: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Potash’s many guises

Potash is defined in various ways. The name originally referred to wood ash or plant ash collected in pots. Potassium carbonate was leached from the ash by soaking it in water. The alkaline solution was then separated from the ash and the water boiled off in cast-iron cauldrons to produce dry potassium carbonate. The solid was used to make soap, glass, and other products.

Nowadays, the term potash refers not only to potassium carbonate but also to any chemical compound, mineral or ore containing potassium in a water-soluble form. The compounds include potassium chloride, potassium sulfate, potassium nitrate and caustic potash (potassium hydroxide).

Before the start of the 20th century, Germany was the only country in the world to practise potash mining. In the 1850s, deposits of minerals and ores containing potassium salts were discovered in a rock salt basin at Stassfurt, a small town near Magdeburg. Two of the most important minerals were the hydrated double salts carnallite, KCl·MgCl2·6H2O, and kainite, MgSO4·KCl·3H2O. The most important ore was sylvinite, a mixture of sylvite and halite. These are the natural mineral forms of potassium chloride, KCl, and sodium chloride, NaCl, respectively.

In 1861, a factory was erected in Stassfurt to produce potash salts from these deposits. The factory produced almost 20,000 tonnes of the salts the following year. By 1909, annual production in Germany had soared to more than seven million tonnes. Some of the crude potash minerals were refined in ‘potassium chloride factories’ that produced a range of potassium compounds, including caustic potash for making soap; potassium chlorate, KClO3, an ingredient of explosives used in firearm percussion caps and the heads of safety matches; and potassium dichromate, K2Cr2O7, a bright orange–red compound using for tanning leather and dyeing textiles.

But well over half of the crude potash mined in Germany was sold as fertiliser. Potassium is one of three primary macronutrients that plants absorb from the soil in relatively large quantities. The element helps plants to grow, regulate their use of water, and combat diseases and hungry insects. The other two primary macronutrients are nitrogen and phosphorus.

The increased use of potash as fertiliser during the second half of 19th century and early 20th century was spurred by the work of German chemist Justus von Liebig. Regarded as the ‘father of the fertiliser industry’, he advocated the application of artificial fertilisers containing the primary macronutrients to boost soil productivity. Before the 1850s, natural materials such as manure, bone meal and limestone (calcium carbonate, CaCO3) were the principal soil additives used by farmers to improve productivity. Calcium is a secondary macronutrient that strengthens plants, stabilises their roots, and protects them against bad weather conditions.

Nowadays potash is mined throughout the world. While Germany still produces significant quantities of potash, Canada and Russia are by far the leading producers. Belarus and China also produce more than Germany. More than 90% of global potash production is used for plant nutrition. The rest is used industrially for the manufacture of soaps, glass, pharmaceuticals, plastics and other products.

The major fertiliser products are potassium sulfate and potassium chloride. They are known in the fertiliser industry as ‘sulfate of potash’ (SOP) and ‘muriate of potash’ (MOP). Sulfur, like calcium, is classified as a secondary macronutrient. Plants need the element to make proteins and for photosynthesis. The chlorine in MOP is a micronutrient that promotes growth in plants. However, chlorine tolerance levels varies across crops. ‘It’s why SOP, which is chloride-free, trades at such a premium to MOP,’ says Edmunds. ‘MOP is the dominant source of potash in the world, but only because it’s the most readily available, not because it is the most preferred. If cost wasn’t an issue, farmers would choose SOP over MOP.’

Many salts

Boulby Mine has the capacity to produce one million tonnes of potash (KCl) annually. The company exports over half of its production and also supplies the British market with 200,000 to 250,000 tonnes each year.

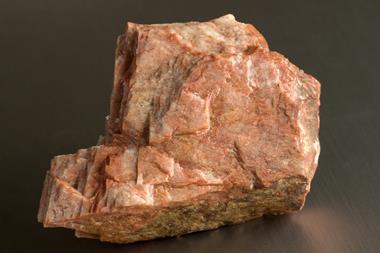

In September 2010, Cleveland Potash extracted samples of a layer of polyhalite rock found 170 metres below the main potash seam. Polyhalite, like sylvinite, is an evaporate mineral deposited from an evaporated sea over 200 million years ago. One might expect a mineral with ‘halite’ in its name to contain an element from group 17 of the periodic table, for example chlorine. Polyhalite, however, when pure, is a halogen-free form of potash. The mineral has the formula K2SO4·MgSO4·2CaSO4·2H2O. The triple sulfate salt mineral derives its name from the Greek words poly and hals meaning ‘many’ and ‘salt’ respectively.

The Sirius Minerals mine will be the largest polyhalite mine in the world with a capacity of up to 20 million tonnes per annum

ICL Fertilizers market the polyhalite under the trade name Polysulphate. Unlike MOP, which provides just one plant macronutrient, polyhalite provides four: potassium, a primary macronutrient, and three secondary macronutrients – magnesium, calcium, and sulfur. The magnesium ion is the central constituent of chlorophyll molecules and therefore is essential for photosynthesis. The nutrient composition of polyhalites varies naturally to a certain extent. The York Potash deposit typically has the following specification: 14% K2O, 6% MgO, 17% CaO, and 19% S. Like SOP, it can be used for crops that do not tolerate chloride at the levels found in MOP. Polyhalite, SOP, and sylvinite are all classified as permitted materials for organic farming whereas MOP is prohibited.

The polyhalite seam at the Boulby Mine runs east from Yorkshire underneath the North Sea for about a mile. Resources in the deposit are estimated at more than a billion tonnes. Cleveland Potash started commercial polyhalite mining in April 2011 and currently produces around 130,000 tonnes per year. With the support of the UK government’s Regional Growth Fund, the company is now planning to increase annual production of the mineral to 600,000 tonnes by 2018 and one million tonnes by 2020.

The York Potash Project will initially target the production of polyhalite from a seam 1500 metres below the surface. Sirius Minerals will market the product as Poly4 – a four in one macronutrient fertiliser – that can be directly applied to the soil or alternatively provide a source of potassium for NPK fertilisers. In the long term, it is possible the company will produce SOP from the polyhalite and also MOP from the large quantities of sylvite present in a seam above the polyhalite seam.

‘The Sirius Minerals mine will be the largest polyhalite mine in the world,’ says Edmunds. ‘It will have a capacity of up to 20 million tonnes per annum when the mine is in full operation.’

The polyhalite deposit provides the largest and highest grade polyhalite resource in the world, according to Sirius Minerals. The deposit has a reserve of 250 million tonnes and a resource of 2.66 billion tonnes. In mining terminology, mineral reserves are classified as deposits that are ‘valuable and legally and economically and technically feasible to extract,’ whereas mineral resources are deposits that are ‘potentially valuable, and for which reasonable prospects exist for eventual economic extraction.’

Consultation and opposition

York Potash submitted planning applications for the new mine, the mineral transport system and the materials handling facility at the end of September 2014. Prior to the submissions, the company invited local communities, businesses and the general public who might be affected by the development to comment on the plans. The company also put on public exhibitions of the plans at locations around Scarborough, Whitby and Redcar.

Many were enthusiastic about the proposals. The York, North Yorkshire & East Riding Enterprise Partnership, for example, expressed delight when the plans were approved last year. Barry Dodds, chair of the partnership, commented in a press release that investment in the potash mine would boost North Yorkshire’s economy by 6% and create around 1000 new jobs for local people. ‘The mine will offer work on a large scale to one of our region’s most deprived areas and these jobs will be available for future generations and will have a wider economic benefit for the area,’ he noted.

But others were not so happy. By June last year, some 29 environmental and other organisations had got together to urge the North York Moors National Park Authority to reject the proposals. The organisations, spearheaded by the Campaign for National Parks (CNP), expressed concern about the impact of the mine on the park and damage to the local tourism economy. They also highlighted the ‘huge disruption’ to residents and visitors during the five-year construction period when movements of heavy goods vehicles on local roads would increase significantly.

‘We remain convinced that the project is completely incompatible with National Park purposes and that the promised economic benefits for the surrounding area do not justify the huge damage to the National Park’s landscape, wildlife and local tourism economy,’ CNP commented in October last year when planning permission was granted.

Sirius Minerals state that the new mine and mineral transport system will both be state-of-the-art. ‘We are extremely mindful of the location of the deposit beneath the North York Moors National Park and take our responsibility for minimising our potential impact on the area very seriously,’ Edmunds says. ‘Our world-leading designs and operational philosophy will set a new benchmark for sustainable economic development in a sensitive landscape.’

He points out that the company will provide funding to local planning authorities to mitigate and offset any potential impacts associated with the project’s development. A total of £68 million will be allocated to tree planting, £60 million for enhancing and protecting the national park and £35 million for safeguarding and promoting local tourism.

Planning approval

Immediately after the final decision notices approving the plans were issued last October, interested parties had the opportunity to challenge the validity of the decision on legal grounds during a six week judicial review period. Although ‘hugely disappointed’ with the approval, CNP decided, on legal advice, not to seek a legal challenge. ‘We will now focus our efforts on making sure this type of major development cannot be approved in National Parks in the future,’ observed CNP chief executive Fiona Howie. ‘These landscapes are meant to be given the highest level of protection by our planning system. But this case makes it clear that these protections are simply not strong enough.’

We will now focus our efforts on making sure this type of major development cannot be approved in National Parks in the future

By the beginning of December 2015, all key planning approvals for the York Potash Project had passed through their respective judicial review windows. ‘We are pleased to be able to put the majority of the approvals work behind us and focus on the implementation of this world class project,’ the managing director and chief executive officer of Sirius Minerals, Chris Fraser, said in a statement.

At the time of writing, York Potash is finalising a definitive feasibility study for the project. The company is confident of announcing positive findings. Construction of the new mine near Whitby is expected to start later this year and take five years to complete. Underground mining is targeted to commence at 10 million tonnes per annum with potential to expand up to 20 million tonnes per annum over several years.

The tender process for the major contracts and various discussions on financing are ongoing, Edmunds explains. Sirius Minerals’s shares are traded on AIM (Alternative Investment Market), a London Stock Exchange sub-market catering for smaller companies that are looking for capital to grow.

The fertiliser company already has a significant number of sales agreements with customers in North and South America, Europe, China and South East Asia. Total sales commitments are in place for almost eight million tonnes per annum, according to the company. Sirius Minerals is confident of its ability to build an even bigger market around the world for their polyhalite fertiliser. But that will be a significant challenge in the long term.

Michael Freemantle is a science writer based in Basingstoke, UK

No comments yet