Suppliers are stepping up production to meet demand as UK targets mass testing

The UK has partly blamed a delay on ramping up testing to confirm Covid-19 cases on a shortage of ‘chemical reagents’. However, there is some mystery surrounding the precise reagents that the government claims are in short supply.

Trade bodies representing the life sciences sector said that inevitably with ‘unprecedented demand for the new [virus] tests across the world, demand is outstripping supply’. But there does not appear to be an outright shortage of reagents. The Chemical Industries Association says that ‘while there is of course an escalating demand, there are reagents being manufactured and delivered to the NHS. Every business here in the UK and globally is looking at what it can do to help meet the demand as a matter of urgency.’

A lot of ingredients make up the test for Covid-19. The virus sample obtained from a patient is deactivated, and virus RNA extracted. The main ingredient in the extraction buffer is guanidinium isothiocyanate, although proprietary buffers contain other reagents such as Triton surfactants, says Matthias Trost at Newcastle University. He is leading efforts to expand local testing facilities.

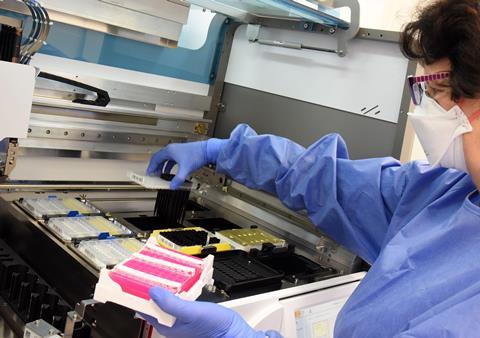

His lab has plenty of the kits, but Trost suggests that many NHS labs – which use liquid handling robots for RNA extraction – will all use the same systems, so it’s possible that delays are caused by supplies of the required buffer running out. ‘Because it’s a proprietary system, it’s not straightforward to change buffers and any replacement needs to be validated.’

The test itself – which makes hundreds of thousands of copies of the virus’s genetic material – is carried out using real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It requires two enzymes – reverse transcriptase to synthesise a strand of complementary cDNA from the virus RNA; and a heat-stable DNA polymerase such as Taq polymerase to amplify the DNA, so it can be detected. Enzyme supply doesn’t seem to be an issue. Identifying the virus genetic materials requires primers and probes. These are lab-made fragments of DNA that attach themselves to target sections of the virus-derived cDNA. Marker labels or probes attach to the new copies of the cDNA strands that are made with each cycle of the PCR machine. The probes’ fluorescence can be detected and used to quantify the original amount of viral RNA.

In Newcastle, the university’s labs are validating different kits – including primers and probes – so that if one source dries up there are viable backups for the NHS. The World Health Organization lists over 200 available Covid-19 tests, although not all of them have regulatory approval.

End to end systems, which cover the whole process including sample swabbing and preparation, are now coming online: Swiss pharma giant Roche recently got approval for its test, and has confirmed that it is working with the UK government on supply. US group Merck & Co is supplying various raw materials and test components for customers working on diagnostics. It reports minimal impact on its supply chain, and says it working closely with customers ‘to ensure a continued supply of products or raw material.’

Writing in the Financial Times, Julian Peto, a cancer epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, suggested the UK has enough PCR machines to test everyone in the country, if every lab in the country were recruited to do tests. Most universities can also make the primers the test requires. Public Health England had been centralising testing – requisitioning machines from university labs. But it is now enlisting help. The Francis Crick Institute in London has repurposed its labs and expects to be able to do 500 tests a day, starting around 6–10 April. The Institute says its testing method has been verified against national standards. The methodology is flexible, allowing for variations in technique that should help protect it against global shortages of reagents and equipment. The methods will be shared with other labs across the country.

Whether the UK can reach its target of 100,000 tests a day for both virus and antibodies by the end of April remains to be seen, says Trost. ‘It is not only reagents shortages [that need to be overcome], it is more instruments, better logistics, more people (who need training) and additional non qPCR assays which will allow other platforms to be used.’

No comments yet