Most animals left in -30°C temperatures wouldn't last very long. Not only would they get hypothermia, but the water in their bodies would start to freeze. Some animals and plants, however, use antifreeze proteins to keep ice at bay. It had been thought that these antifreeze proteins just interact with nano-sized ice crystals, binding to them and preventing the crystals from growing any bigger. Research from Ruhr University in Germany, in collaboration with US scientists, now suggests a second way that these proteins protect against freezing, by

affecting the organisation of water molecules up to seven layers away from the ice-binding site.

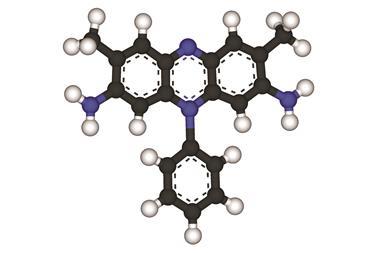

Martina Havenith and her colleagues examined an antifreeze protein from the fire-coloured beetle Dendroides canadensi as it is much more potent than similar proteins found in fish. After dissolving the protein in water, the group used terahertz spectroscopy and computer simulations to watch the long-distance action of the protein on the water molecules.

No comments yet