Compound could drastically reduce toxic side effects associated with a widely used cancer drug by inhibiting bacterial enzyme in the gut

US researchers have identified a compound that could drastically reduce toxic side effects associated with a widely used cancer drug. The research could improve anticancer treatment and drug tolerance among cancer patients.

Matthew Redinbo from the University of North Carolina had worked on cancer drug irinotecan, or CPT-11, for years, but when a colleague started undergoing treatment with the drug he became motivated to address the side effects. Now his lab, in collaboration with clinicians at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, has four candidates that could prevent the debilitating diarrhoea that CPT-11 causes.

Irinotecan is mainly used against colon cancer, but the severe diarrhoea that can be a major side effect of treatment can lead to hospitalisation. This side effect often restricts the dose that can be given to patients and that can limit the drug’s efficacy. ’The difference between reading about what the side effect is and then hearing about it from a friend is a big difference,’ Redinbo says, explaining why he decided to tackle the side effects of irinotecan directly.

The intravenous treatment is a prodrug, meaning it remains inactive until metabolised in the body to give an active drug that prevents DNA unwinding and being replicated in cells. Some of this drug attacks tumour cells but much is deactivated in the liver and transferred to the intestines for excretion. The severe diarrhoea is thought to be caused by reactivation of the drug by bacteria in the patient’s intestines, which then kills the intestinal cells.

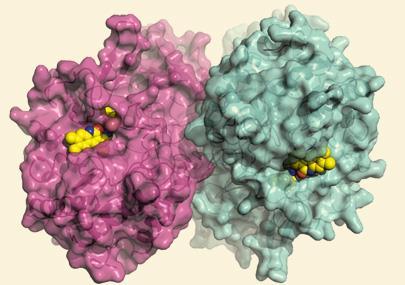

The researchers screened 10,000 compounds and found four potential inhibitors of bacterial beta-glucuronidase, the enzyme thought to be responsible for reactivating irinotecan in the gut. These inhibit the bacterial enzyme, but do not affect other intestinal enzymes because the inhibitor interacts with a small loop in the enzyme not present in its mammalian counterparts.

Redinbo’s collaborators from New York have also shown that mice that received regular oral dose of one of the inhibitors along with irinotecan suffered much less diarrhoea, and had healthier colon tissue, than mice that were just treated with irinotecan.

’The investigators deserve congratulations for an elegant application of science towards the understanding and management of a clinical problem,’ say Leonard Saltz, a doctor who specialises in treating colon cancer at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, US. However, he urges caution, adding ’How to utilise this new evidence in the clinical arena will require a lot of additional investigation.’

This is something that Redinbo agrees with completely. Having shown one cause of irinotecan related diarrhoea and a potential answer to the problem, the team is now set to do what Redinbo describes as the ’real work’ of checking that the compounds are safe. ’If all that looks OK then you can start thinking about clinical trials,’ he says.

Laura Howes

References

B D Wallace et al, Science, 2010, DOI: 10.1126/science.1191175

No comments yet