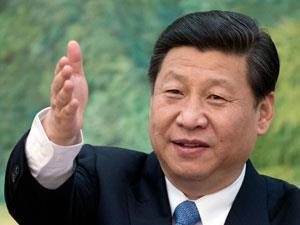

Xi Jinping, China’s president-in-waiting, will need to deal with public anger over industrialisation and pollution

When the new general secretary of China’s Communist party central committee, Xi Jinping, gave his first address to the Chinese people in November, the head of the world’s largest political organisation acknowledged that they yearned for ‘a more beautiful environment’, and that the party would fight for it. This recognition of recent environmental protests by the man expected to become China’s next president marks a shift in thinking that could affect how the country deals with large industrial projects.

Xi is set to take over a society which has changed profoundly in the past decade and this is reflected by increasing dissatisfaction over the state of the environment. ‘A silent revolution has happened,’ says Sun Liping, a professor of sociology at Tsinghua University, adding that the government cannot control people as it once did. ‘This is the true driving force that will make China change.’

However the government explains, the people just do not believe!

Earlier, a report delivered by the current president, Hu Jintao, at the 18th National Congress of the Communist party, admitted that China faces ‘increasing resource constraints, severe environmental pollution and a deteriorating ecosystem’. Hu concluded that the party should be ‘putting prevention first and placing emphasis on serious environmental problems that pose health hazards to the people’.

Under the last administration of Hu and Premier Wen Jiabo, China’s economy quickly rose to become the second-largest in the world. However, political and social reforms have stagnated, income inequality has widened and social mobility has gone into reverse. Many sociologists point to these problems as having engendered a feeling of dissatisfaction in China and this has created animosity between the government and the people.

Tackling the environmental problems and social unrest, which sometimes break out into large-scale environmental protests, Xi faces the difficult task of improving law enforcement, regulation, transparency and participation in decision-making.

The year of the protest

With at least three mass protests, 2012 became the year of environmental action in China. People worried by potential environmental and health effects of huge industrial projects took to the streets, in Shifang in Sichuan province over a molybdenum-copper alloy refinery; in Qidong in Jiangsu province to protest against a planned sewage discharge pipeline project; and in Ningbo in Zhejiang province protests scuppered a planned expansion of a paraxylene (PX) plant.

Since 1996, the number of environmental protests in China has been growing at a rate of 29% per year, according to an official at China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). In November 2012, Zhou Shengxian, the MEP minister, described the situation as ‘a sensitive period for China’s environmental issues’.

Mass protests against large industrial developments are a relatively new phenomenon. One of the first is thought to have been in 2007, with a paraxylene (PX) plant in Xiamen, Fujian province on the receiving end. The protest quickly forced the local government to halt the project. Xiamen’s PX case provided a template for residents in other Chinese cities. PX projects have since been targeted by two other mass protests in Dalian in 2011 and Ningbo in 2012. Zhou says that with stricter regulation, an informed and engaged populace and an assessment of threats to social stability, China’s environmental protests will decline over time.

A lose-lose situation

The protests all tend to share the same features and have a clear demand: ‘not in my backyard’. But there is more to them than simple NIMBYism. A wide range of different interests and issues are involved, including land requisition, relocations and the impact on real estate prices.

Because the environmental issues are apolitical and only involve local governments, mass protest can be used as a politically safe tool for citizens to achieve their goals. For local authorities, maintaining stability is the primary task. When residents’ dissatisfaction erupts, local officials rush to halt the projects and end the protests as quickly as possible.

In these cases, a pattern has been established where citizens have to make some noise to get heard - and the fiercer and more massive the protests are, the greater the chance that the local authorities will bow to public demand. Many observers say that the absence of a strong rule of law, public oversight and participation, means that these unconventional means of controlling industrial planning maybe have unpredictable consequences.

These clashes between local and business interests can often result in a lose-lose situation. For instance, cancelling Qidong’s pipeline project, which had undergone years of scientific assessment, was a victory for the locals. But polluted water from nearby paper mills continues to be discharged into the Yangtze river, which provides drinking water for a large population. The environmental problems that Shifang and Ningbo face have not been resolved by the protests either.

Where is the resolution?

Local governments in China are eager to attract foreign investment to promote economic growth. German chemical giant BASF’s planned methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI) plant in the Three Gorges region is one such example of large-scale foreign investment. When it opens in 2014, it will be the world’s largest MDI plant. However, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and environmentalists are opposing this project as the plant may adversely affect the water security of millions. This follows concerns about the firm’s environmental record in China after a phosgene leakage at BASF’s plant in Shanghai in 2007.

Responding to these concerns, BASF China launched a community advisory panel in 2011 to provide extensive information on the construction and implementation of BASF’s MDI project. The panel is made up of 16 volunteers drawn from specialists, NGOs, the Chinese authorities and the public and will attempt to address concerns about the construction of the MDI plant.

Mu Guangfeng, former director of the department of environmental impact assessment at the MEP, says that the contract between the public and the central and local governments has been broken. ‘However the government explains, the people just do not believe!’ he adds.

Mu says that the 18th National Congress has now ‘denied the model of the past’ where economic development came at any cost. He says that he expects the new leadership will place the emphasis on paying for environmental protection squarely on the shoulders of industry. However, he notes that ‘without changing the political system, nothing can be resolved’.

Additional reporting by Yifei Tan

No comments yet