Eight firms are accused of selling authorships of so-called design registrations issued in the UK in what the study says is likely an attempt to exploit intellectual property to manipulate researchers’ academic standing.

While the UK doesn’t issue design patents like the US, it does offer other similar forms of intellectual property called research design registrations, which provide legal protection to the appearance of products such as their decorations, shape or patterns. Obtaining a design registration gives the owner exclusive rights to produce, import, export and sell products with these distinct features. However, obtaining a patent is a more rigorous process than securing a design registration, as they are not assessed for novelty or innovation.

The sale of UK-registered design registrations is mostly to academics based in India, according to a new study outlining the phenomenon.

Under a scheme introduced by India’s University Grants Commission (UGC) — a department under the country’s education ministry — researchers can earn 10 points for every patent they file under their name outside India towards their ‘research score’. The UGC recommends that an academic have a minimum research score of 120 to be promoted from an associate professor to a full professor. The number of patents a researcher has also contributes to an institute’s National Institutional Ranking Framework score, making it lucrative for India’s researchers.

Study author Reese Richardson, a biologist at Northwestern University, US, says he and his co-authors had been monitoring social media accounts of paper mills, which sell authorship slots on studies already accepted for publication at journals, as well as citations in exchange for a fee. Paper mills often advertise various services, including writing theses, textbook chapters, editorship of textbooks, or being named on awards on WhatsApp, Facebook and Telegram groups, Richardson says. ‘Basically anything that can be used to pad your CV.’

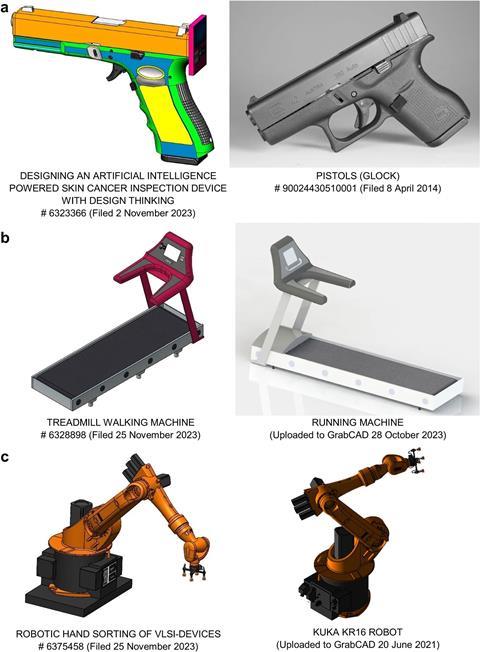

In late 2022, Richardson and his colleagues noticed that the online groups started posting advertisements for what they were describing as patents. ‘What they were selling as inventorship was not actually inventorship at all,’ Richardson says, ‘but they were being issued actual intellectual property rights in countries like Canada, India and the UK and Australia.’

While the design patents and registrations were being issued by countries around the world, the clientele is in India, Richardson says. ‘They make explicit reference to patents being useful for all of these different individual and institutional rankings and accreditation procedures,’ Richardson says, referring to the advertisements.

The Indian authorities should stop incentivising the filing of patents, says Achal Agrawal, a data scientist who founded the India Research Watchdog. ‘Perhaps they can look at the value generated by the patents, but even that is prone to gaming,’ he notes.

According to a 2024 analysis, an estimated 23% of universities worldwide explicitly cite patents and other forms of commercialisation in promotion and tenure criteria at universities. Richardson, however, thinks universities should ditch all quantitative metrics. ‘I think, especially in resource-poor settings, they are only bound to be abused and manipulated,’ he says. ‘They encourage bad behaviour and lead to the rise and influence of these sorts of parascientific organisations that sell authorship slots and inventorship slots on fake patents, sell awards and put together fake conferences.’

References

RAK Richardson et al, Int. J. Educ. Integr., 2025, 21, 15 (DOI: 10.1007/s40979-025-00185-8)

No comments yet