A group of research integrity experts has launched a series of guidelines on how to be an effective sleuth.

Unveiled on 4 June, the Collection of Open Science Integrity Guides (Cosig) contains 27 handbooks that collectively explain how to carry out various research integrity-related activities.

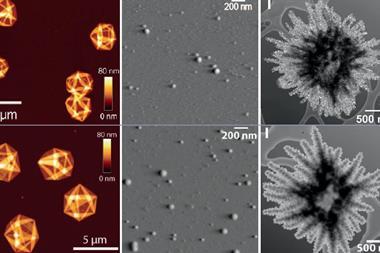

These include best practices for posting comments about studies on the post-publication peer review platform PubPeer, how to spot image-related problems within studies, as well as issues with citations, ethics approval and plagiarism.

The guides also contain some subject-specific suggestions such as antibody verification and non-verifiable cell lines in biology and medicine, identifying problems with x-ray diffraction and x-ray spectroscopy in materials science and engineering, as well as issues in computer science, mathematics and statistics.

‘We wanted to affirm that anyone can do post-publication peer review, especially working scientists,’ says Reese Richardson, a biologist at Northwestern University, US, who is one of Cosig’s creators. ‘I became an active post-publication peer reviewer by acquiring these tidbits piecemeal over the last few years. We thought it would be great to centralise this know-how and distribute it freely.’

Richardson and his colleagues believe that all scientists should be doing post-publication peer review (PPPR) and the practice should be incorporated within scientific practice and training. He believes that only a fraction of problem papers are reported on sites like PubPeer or to journals directly. Moving forward, Richardson and his team are welcoming revisions to existing guides as well as ideas for new ones.

‘Our detection of problematic papers is bottlenecked by how many people are doing post-publication peer review,’ Richardson says. ‘I should also note that PPPR is important for enriching the scientific literature not just for finding problematic papers, but for recontextualising research and updating findings according to our best current understanding.’

‘The Cosig guidelines should help amateurs and experts alike, and reduce unfounded accusations, including those that might arise from personal conflicts or grudges,’ adds Jennifer Byrne, a molecular oncologist at the University of Sydney in Australia who helped create a few of the guides. She also thinks these guidelines could help scientists read the literature more critically.

Days after Cosig went live, a different site – dubbed Retraction Bounty Hunter (RBH) – that links to the guidelines also surfaced, offering to pay researchers to report problematic papers. ‘If the article is retracted within six months as a result of your report, a bounty of $50 (US) will be paid via PayPal or Venmo,’ the site reads.

’I’ve reported clear errors and likely fraud on multiple occasions and have been ignored,’ says Kurt Leininger — who founded Retraction Bounty Hunter, as well as the site publishing services site mstracker. ’RBH will provide a collective voice and professional advocacy to those who report shoddy and fraudulent publications.’

While a few opportunities do exist for full-time paid sleuthing work, Richardson hopes more scientists will take it on as a part-time activity alongside their research. ‘While these guidelines can’t buy the time required for doing PPPR in addition to being a working scientist, they do significantly lower the barrier for entry, providing a comprehensive starting point,’ he says.

‘We definitely need more sleuths,’ Byrne says. ‘We also need journals and publishers to take their concerns seriously. Most sleuths have long lists of seriously flawed papers that they’ve described to journals and publishers, that have never been corrected.’

‘Failing to correct known flawed papers only encourages bad actors, such as paper mills, who typically experience no meaningful consequences for polluting the literature. We need to match our capacity to detect serious errors with an equivalent capacity to correct flawed papers.’

No comments yet