At the end of May, Jolanda Spadavecchia, a nanomedicine and biosensor researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), was banned from conducting research for two years by her institution after multiple research integrity breaches.

As Chemistry World reported at the time, the ban was a result of the second investigation into Spadavecchia’s work by the CNRS after scientific integrity experts penned a letter to the institution asking it to ‘adequately investigate’ allegations of malpractice in Spadavecchia’s lab.

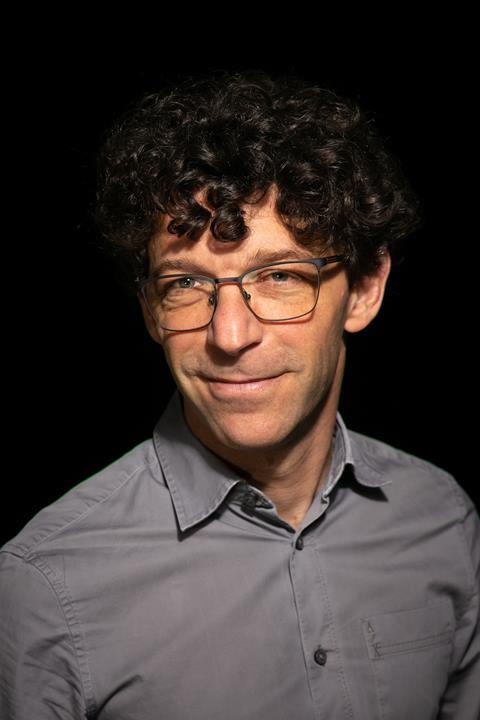

What wasn’t covered extensively in the media, however, was how Raphaël Lévy, a physicist at Sorbonne Paris North University in France – who also received legal threats from a high-profile scientist recently in another unrelated case – blew the whistle. Chemistry World spoke to Lévy to find out more.

How did you first come across Jolanda Spadavecchia?

I spent 18 years at the University of Liverpool, UK. After Brexit, I started to look for positions in France. There are very few professor-level positions, so in 2020, when I came across the announcement for a position at the Université Sorbonne Paris Nord with all the keywords that matched my CV, I had to apply. This is when I first came across Jolanda Spadavecchia. I did take a look at her papers, but not in great detail. I was looking for ideas that would help me write my application and I quickly saw that I would not find them in these articles.

When did you blow the whistle on Spadavecchia’s papers?

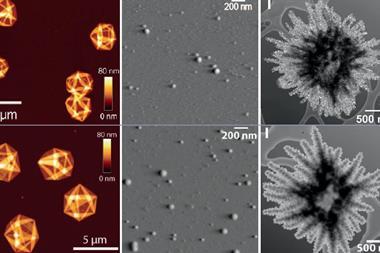

I blew the whistle in February 2021 (with additional observations in April 2021). This was about six months after joining the university. My report mentioned 23 problematic articles. What had happened was that I looked at one article and realised that the same histogram had been reused three times in the same figure, with just changes made to the x-axis range. When I looked at other articles from the same author, I found that the same histogram (or in some cases variants with very minor modifications) was published 15 times spread between eight articles. Some other histograms and other curves had also been reused, as well as some electron microscopy images.

Who did you report the questionable studies to?

I reported the affected studies to the CNRS integrity officer and to the president of the university (who forwarded it to the university’s integrity officer). The response was a first investigation that concluded more than a year later, in May 2022, that many papers needed to be corrected but that no retractions were necessary. I was not too impressed with this decision: how is it possible to correct articles when the data have been made up? In the summer of 2022, Jolanda Spadavecchia started to publish corrections to her articles. The IOP journal Nanotechnology and Dove Press’s International Journal of Nanomedicine rejected the corrections and instead retracted the articles. The other journals and publishers either did nothing or accepted corrections of fabricated data. I started posting on PubPeer at that time and I also informed publishers of the wider context of these requests for correction.

In December 2022, French newspaper Le Monde reported on this story. Shortly after that, an international group of experts on research integrity, coordinated by Dorothy Bishop, wrote an open letter to CNRS affirming the ‘need for transparent and robust response when research misconduct is found’. Eventually, a second complaint against Jolanda Spadavecchia was made to CNRS by an anonymous whistleblower who considered the same articles as me, some more, as well as the problematic corrections. The disciplinary decision and recommendation for 17 new retractions that we have seen recently are the outcome of the investigation that followed that second complaint.

What was the cost to you financially, professionally and personally for blowing the whistle?

I did receive significant backlash for reporting the papers in the first place, but also for commenting on PubPeer, contacting the editors, in short, for insisting that the scientific record should be corrected and that fabrications and falsifications should not be left untouched. The backlash and retaliations took various forms, from general hostility to exclusions from various tasks (including, ironically, teaching PhD students about research integrity).

Eventually, I was even the target of several formal complaints, including one for harassment, for which I had to hire a lawyer. I am a professor with job security who had just landed a big grant (ERC Synergy NanoBubbles), and I was also already well prepared for this kind of thing as I have plenty of experience on research integrity. The important point is that if a student or a more junior researcher had faced such a backlash it is unlikely that they would have been able to stand up to it.

How do you face researchers who are Spadavecchia’s co-authors?

Many mistakes have been made in how this affair has been handled. Maybe one of the more serious ones has been from the start to insist on confidentiality and put the co-authors aside. If, instead, they had been encouraged to look critically at the articles they are co-authors on, they could have already, years ago, become actors of the correction of science instead of collateral victims of unwanted retractions. It would have been better four years ago, but there is still time now.

Are you satisfied with how this case has gone?

Of course not. There was no attempt to protect me, and even institutional complicity in some of the retaliation. This is in spite of the scale and simplicity of the case, and in spite of my track record on research integrity and privileged position. I hope that this case will help improve the situation for future whistleblowers in France.

Would you blow the whistle again on research fraud?

Of course, yes. This is nothing extraordinary. It is what every scientist should do. Not doing it would be committing misconduct (see the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity).

How can whistleblowers be protected?

The protection of scientists who report misconduct must be an obligation for employers. The form it takes will depend on the exact circumstances and the vulnerability of the person. The investigations should be quicker, with more transparency and with visible consequences, in particular in terms of corrections or retractions of articles (and the reasons for those). This is essential for maintaining the accuracy of the scientific record, but also for the protection of the whistleblower. In that sense, the publication by CNRS on their website of the document that lists the articles that should be retracted, together with the reason for those retractions, is a significant step in the right direction.

How can we weed out false positives when it comes to research misconduct?

Focus on the data.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

No comments yet