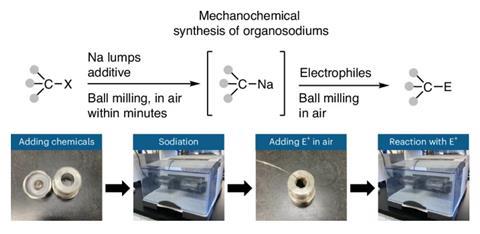

The sodium analogue to ubiquitous organolithium reagents is now easily accessible thanks to a simple ball-milling procedure. The solventless mechanochemical synthesis combines sodium metal directly with an organic halide, providing a sustainable alternative to conventional organometallic chemistry and an intriguing extension to the scope of these reagents.

Organometallic reagents are one of the most fundamental tools in organic chemistry – these carbon nucleophiles are a staple across both industry and synthesis. To date, this chemistry has been dominated by organolithiums which combine versatile reactivity with straightforward preparation and relatively high stability. But, rising demand for lithium-ion batteries has both reduced the availability and increased the cost of this metal for other applications, making alternative organometallics of interest.

Sitting beneath lithium in group one, sodium shares many of lithium’s properties and can likewise form reactive nucleophilic reagents with organic halides. However, their more potent reactivity – organosodium reagents rapidly consume typical solvents such as tetrahydrofuran and diethyl ether – combined with their poor solubility in inert solvents such as hexane, have limited the practical application of this chemistry.

But now, by employing a straightforward mechanochemical procedure, researchers at Newcastle, Birmingham and Hokkaido universities have negated the need for any problematic solvent, producing air-stable organosodium reagents directly from the metal.

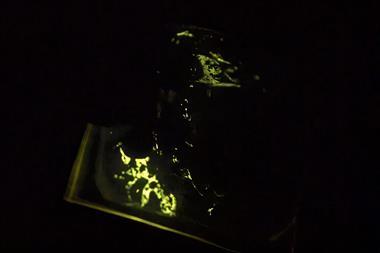

They agitated an organic halide and sodium metal, with a trace of hexane to lubricate the mixture, in a ball mill for as little as 5 minutes under an air atmosphere. The resulting organosodium then immediately reacted with a variety of in situ or added electrophiles, including imines, amides, aldehydes, ketones and esters. The reaction worked for a variety of aryl and alkyl halide substrates (including examples previously inaccessible in solution) and, unlike in solvent-based methods, the team did not observe the homocoupling product, formed when the newly-generated reagent combines with any unreacted halide.

The researchers also demonstrated the approach’s potential for more complex transformations, employing the reagent in a nickel-mediated cross-coupling, the synthesis of antispasmodic drug orphenadrine and the preparation of a second organic reagent, sodium tetramethylpiperidide – a non-nucleophilic base.

The sodium reagent unexpectedly diverged from its lithium analogue in its behaviour towards carbon–fluorine bonds. ‘Fluorine is an ortho directing group, so if you were to take an aryl fluoride with an organolithium, it would actually lithiate ortho to the fluorine,’ explains Peter O’Brien, a synthetic chemist at the University of York. ‘What the authors found was that they could insert the sodium between the carbon–fluorine bond, and that’s a different type of reactivity.’

The simplicity of the team’s method, coupled with the broad scope and good yields, impressed organic chemist Michael James from the University of Manchester who believes that the solvent-free aspect could particularly appeal to industry as they expand their mechanochemical capabilities over the next decade. ‘It’s a huge inspiration for things to come. There’s a big appetite for people to embrace and use technology to enhance synthesis,’ he says. ‘The challenge going forward is how scalable can you make these technologies? As soon as the technology is developed that unlocks that, this starts to become a really, really attractive process.’

For O’Brien, though, this lack of solvent is a mixed blessing: while the solid-state process is undoubtedly more sustainable and likely contributes to the pseudo-stability of the resulting reagent, it could also prove practically restrictive. ‘For a lot of chemistry, you would want to get these reagents into solution to do normal reactions. I think one of the limitations is going to be, having created the organosodium, how do you get it into more conventional reactions?’ he explains.

That being said, he is excited to see where this methodology will ultimately carve out its niche. ‘It’s great to see alternatives like this being developed and it would be interesting to see whether this reagent can transmetallate other metals to allow you to do other types of cross-coupling,’ he says.

References

K Kondo et al, Nat. Synth., 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s44160-025-00949-7

No comments yet