Coating fertilisers with a biodegradable material to slow the rate at which nutrients are released is an established practice. But Xin Jia and colleagues at Shihezi University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have gone one step further by adding another polymer layer with water retentive properties.

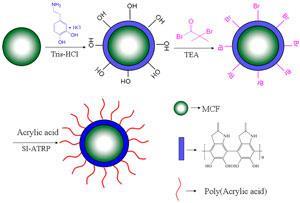

They started out with a multi-element fertiliser containing nitrogen, copper, potassium and phosphorus. They coated the granules with polydopamine – a natural polymer based on the sticky glue secreted by mussels – to make a controlled-release version. Dopamine will polymerise directly onto the granules easily, says Jia, and the speed of nutrient release is determined by the thickness of this layer. They then grafted polyacrylic acid (PAA) chains onto the polydopamine layer using atom transfer radical polymerisation to make an absorbent brush-like coating. The resulting fertiliser is both slow-release and water retentive. In vitro tests showed that the coated fertiliser released nutrients significantly slower than the original, and was around 50 times more absorbent.

The PAA coating also responds to pH changes, which means different nutrients are released under different conditions. This is another very useful property, says Jia. ‘Nutrients could be released selectively in different soils with different pH values,’ he explains.

The team say widespread use of this technique could minimise the environmental burden of fertilisers, reducing the need for irrigation and preventing excess nitrates leaching into waterways. They are now working on similar coatings for commonly used agricultural fertilisers that are vulnerable to leaching, such as urea and ammonium nitrate.

But Keith Goulding, an expert in soil science at Rothamsted Research, says this technology, if commercialised, is most likely to be adopted for high value horticultural crops. ‘Controlled-release fertilisers generally cost more and so are not usually economical in UK broad acre agriculture,’ he says.

William Herz from the Fertiliser Institute in Washington, DC, US, welcomed the new technique, but stresses it would need to undergo safety testing to satisfy regulators. ‘As well as the efficacy of the fertiliser you have to look at the toxicity surrounding it,’ he says, ‘including a detailed look at what the breakdown products are and whether they are taken up in the plant.’

No comments yet