Speciality metals like lithium, neodymium and indium could become restricted unless recycling rates improve, say reports

Supplies of speciality metals like lithium, neodymium and indium could become restricted unless recycling rates improve. That’s the message from the first two of six reports prepared to assess metal supply sustainability for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

’Scientists should anticipate the possibility that they may not have the whole periodic table to work with in future,’ says Thomas Graedel, who led the Global Metal Flows Working Group that compiled the studies.

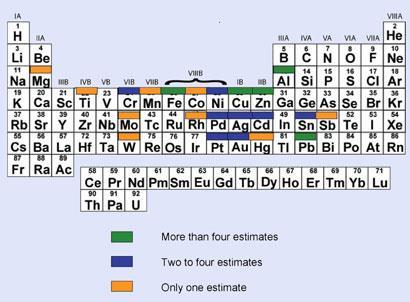

The report series won’t deliver overall supply and demand projections until nearer to the 2012 Rio Earth Summit. Nevertheless Graedel, who is also director of Yale University’s Center for Industrial Ecology in the US, thinks recycling will be pivotal if metal supplies are shown to be limited. ’Except for the major base metals and a couple of the most valuable metals, rates of recycling for almost all metals in the periodic table are low,’ he notes. ’That means that they will be used one time and discarded, and that’s a non-sustainable approach.’

Graedel recommends redesigning products as an interim option for tackling these challenges. Mobile phones and computers can use as many as forty elements in milligram to gram amounts, he explains. ’We use a lot of material in highly complex structures,’ he says. ’We are making it difficult for recycling to deal with, and product designers and materials scientists are not giving this any thought as they roll their designs out.’

The UNEP identifies indium as an example where demand is provisionally predicted to grow strongly, with the 1,200 tonnes needed in 2010 increasing to 2,600 tonnes by 2020. Used in producing light emitting diodes and transparent electrodes for flat screen displays, the UNEP says that under one per cent of indium demand is currently recycled. Claire Mikolajczak, director of metals and chemicals at materials supplier Indium Corporation, concedes that flat screens aren’t being recycled, but argues that 65 per cent of indium supply currently comes from recycling ’spent’ indium material used in manufacturing. ’This recycling ratio will stay constant or improve, so virgin production will need to be increased, but not by such high numbers,’ she says.

Andy Extance

No comments yet