Competition to build battery supply chains means supercharging support to attract investment

Doing something new always comes with an element of risk. And our appetite for risk varies widely, depending on how much is at stake, as well as what the potential rewards or outcomes are. So it is with the burgeoning battery market – particularly for larger batteries aimed at electric vehicles or larger storage projects.

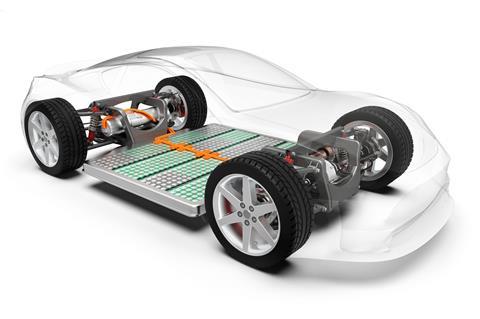

The potential rewards are enormous, as decarbonising transport, grid balancing and other activities will drive massive demand for batteries. But there are risks, not least because of the vast amount of capital required to build a battery gigafactory. Sometimes those risks will outgrow investors’ appetites, as UK battery startup Britishvolt recently discovered to its cost. The holders of the purse strings must balance those risks and decide where and how to commit their resources.

Many aspects will play into those decisions: Should they back established, proven operators, or look for the emerging technology that will supersede them? Is there access to the appropriate workforce, supply chain and infrastructure? Is there an established local market (batteries are heavy and costly to transport, and there are increasingly political measures in place to discourage exports and encourage local production)? What support is available from local and national governments?

With vast numbers of plants being proposed worldwide, the companies and governments hoping to attract investment to their projects can make choices that either exacerbate or mitigate the risks. Companies must demonstrate that they will use investors’ funds judiciously and provide a likely return on the investment. Governments for their part can assuage risk by providing a stable regulatory and policy environment for companies to operate in: uncertainty will always hamper commitment – regardless of the level of any direct investment or subsidy that may be promised.

For years, China has poured resources into creating a world-leading battery industry, while recent and forthcoming US and EU policies offer huge incentives to domestic production. Others will undoubtedly follow.

Such support, naturally, also needs to be affordable. Done well, it can establish a thriving industry with huge growth potential that will pay dividends to domestic economies – regardless of whether the companies involved are home-grown or foreign multinationals. But done badly, without strategy and coordination, it risks wasting resources and even prompting further damage as the associated industries – such as vehicle manufacture – dwindle and relocate.

No comments yet