Payal Joshi draws inspiration for organic mechanisms from graceful avian poses

My fascination with bird photography started when I came across stunning bird pictures shared by expert photographers on Twitter (now X). Inspired by this, I started photographing birds to share them on social media. At first, I began noticing the eye detailing, species differences and their unique behaviour in the natural habitat. However, the pursuit of photographing birds deepened when I visualised birds as not just enigmatic creatures, but as living metaphors of organic chemistry.

It all began with a typical day in my lab planning organic reactions and following industry protocols. I was troubleshooting a difficult step in a reaction that refused to work – numerous trials failed and I returned home in frustration.

Stepping away from the problem, I headed to the terrace to photograph birds. As I watched, I saw a sudden flash of a pristine white winged bird – an egret glided past me and rested on a tree to collect raw materials for building a nest. Observing the egret’s movements as it bent twigs and broke them off the tree struck me with an idea that these movements are like the Diels–Alder reaction mechanism. The egret’s neck and calculated wing movements echoed the smooth, concerted mechanism of a Diels-Alder reaction.

I photographed the bird movements and returned to my desk to draw reaction schemes; only to realise that the answer to my problem was trialling the Diels–Alder reaction. From that day on, my perspective shifted: bird watching, photography and organic reactions connected with each other like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

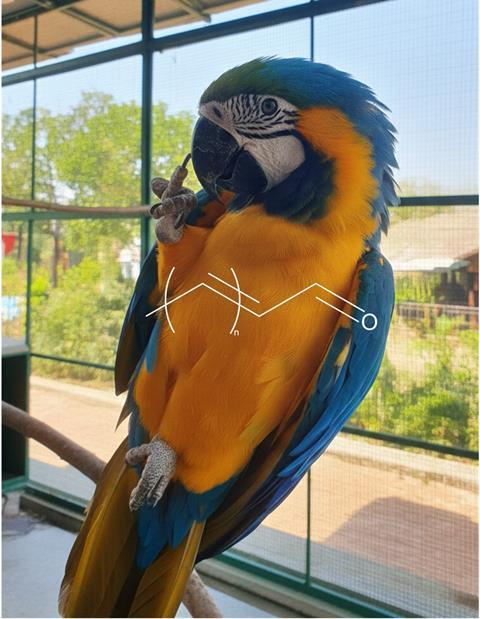

I started visualising organic reactions and molecules in the behaviour and physical attributes of birds. With their aerodynamic efficiencies and majestic flight, birds became more than muses – for me, they became metaphors for molecular behaviour. The sweeping curvature of an egret’s neck was synonymous with rearrangement reactions. The Javan Myna’s crest looked synonymous with chiral centres in a molecule. A wild idea in my head became clearer as I combined my bird photos with organic structures in ChemSketch to bring my vision to life.

As my mind adapted to see organic reactions in bird behaviour, my wildest imagination made me look at the white occipital plumes of the black-crowned night heron, which I related to functional group substitution effects exerted on aromatic rings – decorative but influential. Just as those specific feathers or plumes play a role in species identification or mating displays, functional groups such as OH, NH2, NO2 and COOH alter the electron distribution, reactivities and regioselectivity in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. Going further, the vibrant colourful plumage of blue-and-yellow macaws reminds me of conjugated π-systems, like those found in carotenoids, organic pigments and azo dyes.

The most profound effect of bird photography was how it enhanced my visual perception in my daily lab work. Birding taught me to look carefully and analyse spectral pattern details that are often hidden in the subtleties. This attentiveness to visual detailing sharpened my ability to read spectral patterns, especially in complex NMR or mass spectrometry data, where minor peaks or shifts hint at crucial structural information.

Observing birds and photographing them is both a meditative reprieve and a reminder that chemistry is essentially an abstract concept that needs visual representation beyond textbooks. I am no Jane Goodall, but in my own small way, photographing different birds taught me that quiet observation can reveal hidden patterns in chemical reactions and data. Bird photography honed my visual discipline, patience and systems-level observation skills, deepened my understanding of complex concepts of organic chemistry and made me a better chemist.

Whether I am adjusting exposure on my camera to take best advantage of natural light, or optimising a synthesis route in the lab, I work with the same posture: quietly alert, scientifically grounded, and ready for that fleeting moment when everything aligns; be it a bird in-flight or a molecule finding its perfect form.

No comments yet