Contributing to water security through citizen science

Together with his colleagues, Fred Lee is on a mission to involve the Hong Kong public in water research.

‘We want to show people that there is actually a great potential to perform citizen science projects in Hong Kong,’ says Lee, who is a professor and head of science at the School of Science and Technology at the Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK). ‘I think it is very challenging [to do citizen science here] because Hong Kong is very small and crowded and people in Hong Kong are very busy.’

Investing in citizen science

For a number of years, Lee and colleagues have been part of FreshWater Watch, a programme sponsored by HSBC. More than 20 publications have resulted from data gathered by over 8000 of the company’s employees across 36 countries – an interesting experiment in and of itself when considering the reach and impact enabled by corporate sponsorship of engagement programmes.

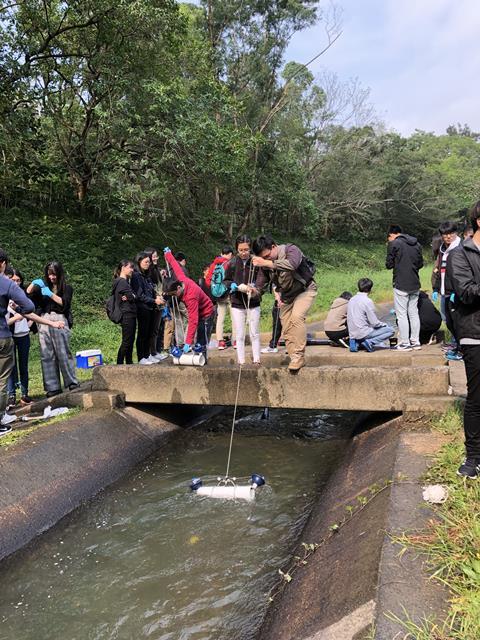

The team recently published data from two years of water sampling and analysis across seven of Hong Kong’s streams and rivers. Each of the sampling sites were in public locations no further than 5.5km from official government sampling locations, meaning that the citizen data could be compared with official measurements and provide additional information from diverse locations along each of the waterways.

‘The citizen scientists do the on-site measuring of the water quality parameters, for example pH, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, temperature and turbidity,’ explains Steven Xu, an associate professor at the School of Science and Technology at OUHK. Citizen scientists borrow the necessary equipment in advance of their fieldwork, measure each of the parameters and collect water and microalgae samples that are returned to the OUHK laboratories for analysis.

As Xu explains, initial training for each of the 250 volunteers was key to the success of the project. ‘They have the chance to practise how to do the water sampling and on-site measurement, so that you make sure that they know what is the background and the whole picture of the project, and what they need to do on site and after that.’

Each small team also has a ‘citizen science leader’, a volunteer who attended lectures and practical workshops to ensure they were experienced in sampling and data collection and confident enough to train team members to perform tasks competently. ‘They have a level of passion to get involved in this project; they are passionate and make us have a passion to share our knowledge,’ says Xu.

Data reliability

Xu and Lee were keen to investigate the reliability of the citizen-generated data by comparison with official data collected from the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) of Hong Kong. The data for water temperature and conductivity was found to strongly correlate with official results, with moderate to strong correlations between the two sets of results for water pH, turbidity and dissolved oxygen levels.

In addition to training volunteers, the research team tried to minimise any errors in the citizen-generated data by sending more than one collection team to each sampling site.

‘If there is some very abnormal data, we cannot rule out that some of them did not perform the measurements – they just took the equipment and had some fun,’ explains Lee.

Both Xu and Lee are convinced of the validity of citizen science as a tool to measure water quality, particularly for the hundreds of rivers and streams in Hong Kong that aren’t regularly analysed by the EPD.

‘It’s very difficult for us to analyse many rivers at the same time … but when we have the help of the citizen scientists, then we can do it,’ Lee explains. ‘We can theoretically analyse all the rivers in Hong Kong at the same time.’

Water Buddies

Xu and Lee also believe that citizen science projects are an important way to improve formal and informal science education. They work as part of the Water Buddy programme that was initiated three years ago to work with younger scientists and have engaged with more than 100 schools in Hong Kong.

Reaching Hong Kongers of all ages is important for Xu. He worries about the large numbers of people who are ‘living beside a river but they know nothing about it’.

For Lee, the changing in attitudes and understanding of participants is clearly evident. ‘Through the programme, I think they [the public] learn something, and also they know why it’s important to perform the water research and conservation, and how it’s important to protect our environment,’ he explains. ‘This is why I really love to work on the citizen science projects.’

No comments yet