What’s next for chemistry outreach after International Year of the Periodic Table?

This year, all over the world, a spotlight has shone briefly but brightly on the periodic table, opening up conversations about chemistry. 150 years since the discovery of periodicity, 2019 was a perfect candidate for a year-long celebration of the most iconic diagram in our discipline.

Children have memorised it and sung songs of the elements; arrays of cupcakes have been baked, iced with element symbols and then devoured; and countless science outreach events have explored the origins, history and future of the building blocks of our universe. But what comes next?

As chemists we don’t need to be convinced of the importance of the elements and our subject for society, but sadly some members of the public still seem to feel detached from both.

Staying in the spotlight

In their recent Nature Chemistry article, ‘Finding the Central Science’, Renée Webster and Margaret Hardy explored chemistry’s ‘lack of visibility in relation to other disciplines’.1

In their recent Nature Chemistry article, ‘Finding the central science’, Renée Webster and Margaret Hardy explored chemistry’s ‘lack of visibility in relation to other disciplines’.

One of the issues explored by Webster and Hardy is the challenge of translating chemistry ‘beyond its own borders’, outside of discipline-specific publications (such as this very magazine) and into the popular press. For example, the pair highlight that the number of Google searches for chemistry spike at the time of the year that the Nobel prizes are announced. To keep chemistry in the spotlight, we need to tell stories that cause spikes year-round.

So how do we do that? Well, one way is to try to find ways to connect chemistry to important events that have already captured the attention of the public. We need to bring chemistry to where people already are and to what they’re already reading, watching or listening to. Mirroring the excellent work of the infographics by Compound Interest, we should pitch mainstream media stories that link chemistry to sporting competitions, cultural or religious festivals and news stories, and remind people that chemistry touches all of our lives.

I think it’s also high time for some prime-time chemistry TV shows, or rather a new series on one of the streaming giants. And of course, we need to get even better at making our breakthroughs more relatable.

Chemistry is undoubtedly tricky to communicate to non-experts, but we have to find ways to tell stories about our central science that connect with people and their lives.

In some ways the elements, when arranged in their table, are so ubiquitous that they feel disconnected from our everyday lives.

Ironically, the periodic table, despite being such a recognisable symbol of our science, can be a hindrance to making those connections.

In his book Periodic Tales, Hugh Aldersey-Williams clearly articulates something that I’ve often thought but have been unable to eloquently express: ‘The table seemed in some funny way to belittle its own contents. With its relentless logic of sequence and similarity, it made the elements themselves, in their messy materiality, almost superfluous.’

In some ways the elements, when arranged in their table, are so well known, so ubiquitous, that they feel disconnected from our everyday lives. Almost like they’ve been tidied away and aren’t available to be played with. And in part, as expressed by Webster and Hardy, the table suggests a sort of completeness to our science, as though chemistry knowledge and discovery happened as part of history, not in our present or future.

Sibrina Collins, executive director of Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technical University in the US, has explored ways to embed chemistry in popular culture in order to better connect with her students.2,3 She likes to make sure that we ‘culturally connect’ with people, ‘so they can see how chemistry directly impacts society’.

Sibrina Collins, executive director of Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technical University in the US, has explored ways to embed chemistry in popular culture in order to better connect with her students. She likes to make sure that we ‘culturally connect’ with people, ‘so they can see how chemistry directly impacts society’.

‘I loved Marvel Studios’ Black Panther,’ says Collins. ‘As I watched the film, I just kept wondering where the fictional element vibranium would fit on the periodic table.’

Collins then set this question for her general chemistry students to answer. ‘It was really a thought experiment, which allows students to understand for themselves how the periodic table is arranged,’ she explains.

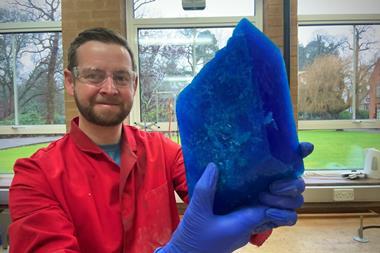

Collins’ work extended beyond university students to high schoolers, who were invited to make their own ‘vibranium solutions’ in the university laboratories. Through this process, they learned more about copper and cobalt and their importance for our everyday lives.

Additionally, one of the main characters in Black Panther is Shuri, a prodigious talent as a scientist and engineer. She is also a young black woman – a refreshing change from stereotypical representations of Stem professionals by Hollywood, and an important role model for a new generation of scientists.

For me, Collins’ work is just one example of the way that we should try to weave chemistry into public conversations and our culture. The IYPT has been a resounding success throughout 2019 but the elements, the table and our discipline need to feel current, accessible and expansive if we’re going to keep the spotlight shining.

No comments yet