Chemistry is worth shouting about – so why are we being so boring?

Poor old chemists. As soon as they do anything sexy, their most successful efforts are often rebranded as molecular biology, nanotechnology, prebiotic evolution, protein engineering, materials science or anything so long as it avoids the c-word. Chemistry has about as much resonance with the average person (whoever that is) as ‘engineer’, ‘terms and conditions’ or ‘annual tax return’.

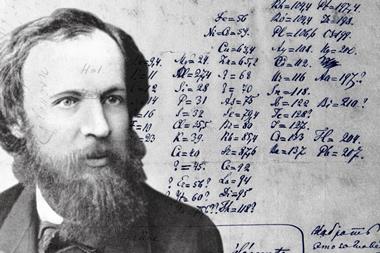

Will this change with this year’s hoopla around the 150th anniversary of the publication of Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table? Will this anniversary turn out to be an amazing opportunity for outreach and public engagement? Will it spur mass adoration and worship of the central science?

Or will the global festivities around the International Year of the Periodic Table be yet another deadly example of all those initiatives that preach to the converted? And, when it comes to the other seven billion or so people on our planet, will it trigger a collective shrug, a yawn or – worst of all – fail even to register a quantum blip in the collective consciousness?

The good news is that the periodic table is worth making a fuss about. This feat of elemental accountancy is a dazzling, unifying concept that help us describe and understand our world, to predict the appearance and properties of matter on Earth and in the universe and, through its organisation, offers a window on the quantum domain of orbitals and energy levels.

Even better, the periodic table is a living thing. Chemists are now exploring the superheavy elements in a vast, unknown landscape. Its farthest regions promise new kinds of chemistry that have not been observed before. Perhaps our concept of the atom may be challenged beyond the element oganesson by loose congregations of protons and neutrons that lack the time to attract and capture an electron.

The table also shows how chemists led the way in understanding the meso scale, bridging the bewildering complexity of biology and the simplicity of physics to help explain the messy stuff of everyday life.

But the origins of this year’s potential big bang of chemical understanding lie in a proclamation from a bureaucracy that is hardly known for its skills at kindling inspiration and jaw-dropping awe.

Brand awareness

On 20 December 2017, the United Nations’ General Assembly ‘recognised the importance of raising global awareness of how chemistry promotes sustainable development and provides solutions to global challenges in energy, education, agriculture and health’. I don’t find it hugely reassuring to know that this UN initiative has the full backing of Iupac, Iupap, EuChemS, IAU and the IUHPST (you can look them up).

Scientists love to pontificate about public engagement but usually consult professors of public engagement (I’m among them) – some of whom struggle to engage with the peer group in their ivory tower, let alone the legions of lovers of the Kardashians. For me, it is an enduring puzzle why scientists and engineers rarely consult the multi-billion advertising and marketing industry that engages with millions of people every day of every week.

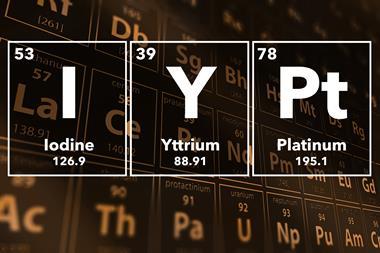

Even the most junior member of that vast global enterprise could have told them that, when it comes to branding, ‘The United Nations International Year of The Periodic Table of Chemical Elements’, and ‘IYPT 2019’ are stinkers of the most sulfurous, telluric, thioacetonic kind.

To be fair, it is common for scientists to fall at the first hurdle of public engagement. Many don’t fully appreciate that there’s no such thing as ‘the public’ – in reality is a mosaic of diverse audiences. Any idea that they are a single entity is a mirage. As a result, scientists often don’t have a clue who they are really trying to engage with. They have a laudable appetite to explain but forget that engagement with their target audience has to start somewhere. Having to think about the five million or so people who walk through the doors of our five museums each year, I know that there’s only one place to begin: with the interests and preoccupations of the target audience.

In Germany, for example, it could start with Angela Merkel, the country’s best-known quantum chemist. In England, it could be how Gregory Winter, its newly-minted chemistry Nobel prize-winner, used protein engineering to make something like £900 million over a 25 year period for the Medical Research Council. In the US, it could begin with battery guru Donald Sadoway, whose skills at lecturing have blown away Bill Gates, among others.

The point is that people don’t have to know about chemistry to roast their food, enjoy the colours of exploding fireworks or wash their hair. The first step to raise the profile of chemists is to think less about how to broadcast the periodic table and more about how to persuade the target audience to listen.

Let’s hope all the ballyhoo will start a wider conversation about the central importance of chemistry.

Roger Highfield is director of external affairs at the Science Museum Group.

3 readers' comments