Researchers in Switzerland have developed a method to create electronic membranes that are thin and flexible enough to wrap around a human hair. The electronic films can also be made transparent, opening up the possibility of creating smart contact lenses, which could monitor the physiological state of the wearer’s eyes, for example.

Giovanni Salvatore and colleagues at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology created the 1µm thick electronic circuit by first coating a rigid support, such as silicon or glass, with a layer of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). A parylene film was then deposited on the PVA by thermal evaporation. The various components for a thin film transistor are then added by sputtering or atomic layer deposition as appropriate. These include a semiconductor consisting of a 15nm film of amorphous indium gallium zinc oxide, a 25nm thick film of aluminium oxide, and contacts made from films of either titanium and gold or, for a transparent product, 100nm of indium tin oxide. The circuit is then patterned using standard UV lithography techniques.

The entire chip is then immersed in water, which dissolves the sacrificial layer of PVA. This separates the silicon or glass base from the membrane holding the circuit, which remains floating on the water’s surface.

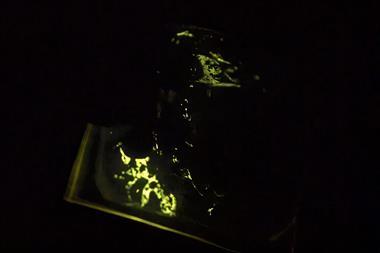

‘This can then be fished out and applied to a range of surfaces,’ says Giovanni. To highlight the extreme flexibility of the membrane, the team draped a sample over fragments of human hair on a slide. The electronic ‘skin’ proceeded to wrap itself around the hairs, which have a radius of around 50µm.

To demonstrate the potential applicability of the electronic membrane, the researchers integrated a small section of the film with a tiny gold-based strain gauge, whose electrical resistance changes upon distortion. This assembly was placed on a plastic contact lens, with the transistors on the electronic film able to amplify signals from the gauge. This, says Salvatore, could be a way to monitor changes in the pressure of the fluid in the eye that can signal the onset of glaucoma. Issues of powering such a device, preferably wirelessly, remain to be resolved Salvatore concedes.

Commenting on the work, John Rogers, an expert in flexible electronics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the US, says: ‘The results, which use zinc-oxide-based semiconductors, confirm similar findings achieved with other active materials, such as silicon and organic polymers.’ He adds, ‘The resulting broad palette of materials and processing options suggests a bright future for such classes of electronic systems.’

No comments yet