Nina Notman looks at the group and individual efforts to promote racial equality in academia

In the past decade, UK universities have taken great strides in advancing gender equality in the Stemm (science, technology, engineering, medicine and mathematics) subjects. The Athena Swan charter, started in 2005, has been a key part of this change, supporting and recognising the efforts of universities to address the loss of women across the career pipeline. Coordinated by the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU) – a charity funded by UK higher education organisations – 134 UK institutions currently hold over 500 Athena Swan awards between them.

In January 2016, the ECU will launch the Race Equality Charter Mark. Its remit: to improve the representation, progression and success of black and minority ethnic (BME) academic staff and students. ‘Race is incredibly emotive and difficult to talk [about] and universities were struggling as to where to start,’ says Claire Herbert, an ECU senior policy advisor. ‘We took the decision that it would be useful to set up a framework for them to work through, to bring the success Athena [Swan] has had in gender equality to race equality.’

Attainment gaps

There is little doubt about the extent of the current disparity in race equality in the UK. In 2014, a report commissioned by the Royal Society crunched the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s 2011–2012 numbers, finding that within chemistry departments 19.1% of EU-domiciled undergraduates (students that normally reside in EU countries) and 28.1% of masters students were from BME groups. These proportions plummet at each stage of the career pipeline, falling to 11.8% of EU-domiciled postgraduate students, 8.4% of researchers, 7.2% of lecturers, with finally just 2.9% of chemistry professors from BME groups. The latest available Office for National Statistics data estimate that around 12% of the English and Welsh population are from BME groups.

Race is incredibly emotive… universities were struggling as to where to start

None of these proportions are directly comparable. For example, current BME chemistry professors will have been students at a time when a smaller proportion of their peers were from BME backgrounds. The trend is also less clear when factoring in how the proportions vary between each BME group and sexes within these groups. Nevertheless, the data suggest the possibility of a leaky pipeline.

The considerable gap between the proportion of UK-domiciled BME students receiving first or 2:1 degree classifications is also cause for concern. According to the ECU, in 2012–2013 around 57.1% of UK-domiciled BME students received a top degree compared with 73.2% of white British students – an attainment gap of 16.1%.

The US statistics tell a similar story. Around 63% of US residents are white, according to the latest US census. However, a 2013–2014 survey of the top 50 US chemistry departments, conducted by the US-government funded initiative Oxide (Open Chemistry Collaborative in Diversity Equity) in collaboration with Chemical & Engineering News, found that 82% of their academic staff were white.

Investigations into this 19% disparity have revealed a complex story. For example, those of Asian or Pacific islander ethnicity (considered together in the survey) are over-represented, holding 13% of the faculty positions while only representing 5% of the overall US population. This means the remaining approximately 5% of faculty positions are held by so-called underrepresented minorities (URM) that compose around 32% of the overall population, including African American, Hispanic, Native American and multiracial academics.

Like in the UK, this survey found significant drops in the representation of minorities as the faculty rise through the ranks and earlier surveys uncovered a significant drop in URM proportions at later career stages.

Rigoberto Hernandez, Oxide’s director and professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, explains that as well as data collecting and evaluating the status quo, Oxide takes a top-down approach to improving equality within US university chemistry departments. ‘We work with the chairs of the chemistry departments to try to change policies and procedures in a way that lowers barriers for everyone,’ says Hernandez. ‘The difference is that the barrier is greater for a member of an underrepresented group than for everyone else.’

Sign of quality

The ECU’s Race Equality Charter Mark also takes a top-down approach, and is currently only available at the institutional level. The ECU completed a pilot of the application process in August 2015, with eight of the 21 participating universities receiving a bronze award. ‘For Athena [Swan], first time bronze applicants’ success rate is around 50%,’ explains Herbert. ‘We therefore thought the race [equality charter mark] chance of success rate was reasonable.’

The success rates are indicative of the rigorous standards for these charter marks. The application process for the Race Equality Charter Mark is ‘really quite intense,’ explains Debbie Epstein, diversity and inclusion manager at King’s College London, which earned a bronze award in the pilot study. ‘There’s extensive data gathering and analysis and a survey that looks at issues particular to race for both staff and students.’ With the help of focus groups and networks, an action plan for the next three years must also be compiled.

After this time, universities must demonstrate they have worked toward that plan – and put another in place – to renew their mark (they can also ‘upgrade’ marks stepwise to silver and then gold). ‘For us this [award] is just a starting point,’ says Patrick Johnson, head of equality and diversity at the University of Manchester, which holds a bronze Race Equality Charter Mark. This continual development process is ‘what we like about this [award] compared to other awards’, he explains.

Yet even outside awards, changes are emerging at a grassroots level. As with many situations in life, aspiring BME students and young researchers will often look to role models and mentors for inspiration and practical advice to overcome any barriers to success they may perceive.

Diversity DJ

One such person is Mark Richards, senior teaching fellow and head of outreach at the Imperial College London’s physics department. Richards’ parents moved to the UK from Jamaica in the 1960s. He was born in Nottingham in 1970 and grew up in the vibrant Caribbean community there.

When Richards left home to go to university, he wanted to maintain strong links with that community. ‘I always felt that it was important to keep my connection with that, because that’s part of what made me what I am,’ he says. ‘For me, being a DJ was a good way of doing that.’ Richards started his musical career – under the pseudonym DJ Kemist – during his undergraduate chemistry degree at the University of Manchester. This is something that he continues to do today, and uses music as a tool to enthuse school students about science during outreach events. ‘I explain the physics behind doing a remix and how you combine audio wave files and the importance of understanding about waves,’ he says.

Richards is a strong advocate for greater diversity in universities, with a particular focus on increasing the proportion of Caribbean students in top universities. ‘I want to see more people like myself studying subjects like physics at places like Imperial,’ he explains. Richards is a member of Imperial As One, a network of BME staff members that advises the college on equality and diversity matters both related to students and staff. The group also run mentoring schemes, outreach activities, symposia and annual diversity lectures. Richards also sits on Imperial’s overarching equality and diversity committee, which takes a top-down approach to eliminating discrimination.

Richards thinks that the biggest hurdle for Caribbean students is getting them to consider top universities in the first place. ‘The problem stems very early on. I have been involved in lots of programmes that nurture the potential of young people and guide them through those difficult teenage stages so that they could become potential students here.’

Richards says a two-pronged approach is needed: aspirations and preparation. He has been involved in initiatives that both bust the myth that ‘Imperial doesn’t take students from our school’ as well as those that help students obtain top grades at A-levels. ‘Some schools are better at, say, converting an A to an A* than other schools,’ he explains.

Head of the class

Another scientist with Jamaican roots who is passionate about ensuring equality is Marion Brooks-Bartlett, who has just been awarded a chemistry PhD jointly from University College London (UCL), UK and Uppsala University, Sweden.

The number of black people really falls off… it can be very lonely

‘I want to be involved straight away when I hear that a project to promote diversity is going on,’ she says. At UCL, Brooks-Bartlett sits on the self assessment team for the chemistry department’s Athena Swan award (they currently have bronze status), and is a founding member of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s inclusion and diversity committee. This committee has a wide remit, including advising on how best to ensure RSC-run activities are inclusive and preparing best practice reports for both universities and industry.

Brooks-Bartlett also teaches at a Saturday school run by the Croydon Supplementary Education Project that focuses on supporting the Croydon BME school-aged community. ‘I’m teaching GCSE science and part of my role is to also talk about black history with the students.’ Like Richards, her motivation is to encourage engagement: ‘There is a huge drop off with achievement for ethnic minority groups as you go from Key stage 2 [age 7–11] to Key stage 3 [age 11–14]. It’s melting down from a really young age.’

UCL was one of the universities to be awarded the bronze Race Equality Charter Mark in the pilot. And Brooks-Bartlett is excited about seeing the university’s three year action plan coming to fruition. ‘The number of black people really falls off [for PhD students compared with undergraduates] and it can be very lonely,’ she says.

Faith in fairness

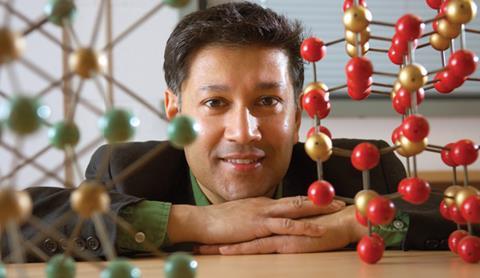

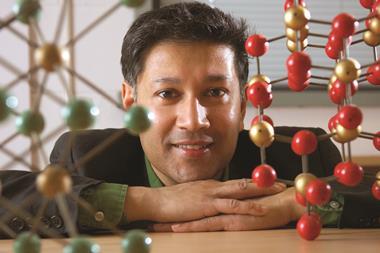

Earlier this year, the Royal Society launched a diversity committee to promote diversity across the breadth of the society’s activities. Saiful Islam, professor of materials chemistry at the University of Bath, is a member. Islam was born in Pakistan to Bangladeshi parents and moved to London in 1964 aged one year. ‘Then war broke between the two Pakistans – west and east – and we stayed in the UK,’ Islam explains.

Life in the UK for a young British Asian at that time wasn’t always easy. ‘As a teenager in the late 1970s, there was verbal racist abuse and violent abuse as well; I’d get beaten up by skinheads,’ Islam says. By contrast, Islam’s personal experience of academic life has been welcoming and inclusive.

Prior to the formation of the Royal Society’s diversity committee, Islam served on its predecessor: the equality and diversity advisory network. ‘The diversity committee formed this year has proper standing committee status of the Royal Society,’ he says. This is an indication of how much importance the Royal Society is now giving to ensuring equality across its activities and to increasing participation from underrepresented groups. ‘The Royal Society feel that diversity is essential in delivering excellence in Stemm and that studying and working in science should be open to all,’ Islam explains. ‘I got involved is because I’ve always believed in greater fairness and equality in society in general.’

As an atheist and humanist, Islam has an awareness of other prejudices. ‘I sometimes wonder about the kind of reaction my name gets, especially now with aspects of religious extremism.’

Islam also participates in outreach activities and is a regular speaker for The Training Partnership, which provides study days aimed at inspiring and motivating GCSE and A-level students. ‘I give lectures to 900+ A-level students using 3D specs. It’s great to see really mixed audiences coming from different backgrounds,’ he says. ‘In my talk I mention that I went to a comprehensive school in Haringey, north London; I give a positive message that science is for everyone, but you do need support. One factor in my success was having some good mentors along the way.’

Taking the initiative

Malika Jeffries-El, associate professor of chemistry at Iowa State University, US, is a member of the Oxide advisory board and has participated in a number of American Chemical Society (ACS) diversity initiatives. As a female African American, Jeffries-El says she is very aware of her minority status in the scientific community.

‘When I first got started in science, I really just wanted to do science. But I started to realise that I couldn’t ignore the role that gender and race both collectively played in my experience,’ she explains. ‘I have had a good support network of people who have helped me advance. But I have also encountered people who have been detrimental to my success. If I didn’t have this other half to counterbalance it, I don’t think I would be where I am.

‘I realise that there’s another population coming behind me who may not have connections and opportunities, and if they come across these negative people early in, they’re going to just leave.’

Jeffries-El helped set up the ACS Women Chemists of Color program and is now one of its advisory board members. ‘There were ACS programmes that served women and there was a committee on minority affairs,’ she says. ‘But it was identified that [women who are also from a minority ethnic group] have a different set of issues and needs that may not be being specifically met by either group. And we therefore started doing activities around that.’

The initiative raises awareness, gathers data and runs networking events and symposia. Jeffries-El is also heavily involved in promoting diversity at Iowa, and plans to continue in that vein when she moves Boston University in January.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

No comments yet