Chemical recycling, an alternative technology for reclaiming plastic waste, has been gaining traction in recent years. Sometimes called advanced recycling, this technology refers to processes that break plastics down into a range of chemicals, rather than simply mechanically breaking them apart for remoulding. Chemical recycling is still in its infancy though, and now a new report from two environmental groups claims that it is doomed to fail. But is this the whole story?

The Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network’s (IPEN) report states that chemical recycling won’t work at scale and creates new and dangerous waste streams. The groups are now calling for a moratorium on new chemical recycling plants in the US. But some experts are warning that such calls are premature as the term covers many different technologies and that are still finding their feet.

Chemical recycling is more of a marketing and lobbying tactic

Judith Enck, Beyond Plastics

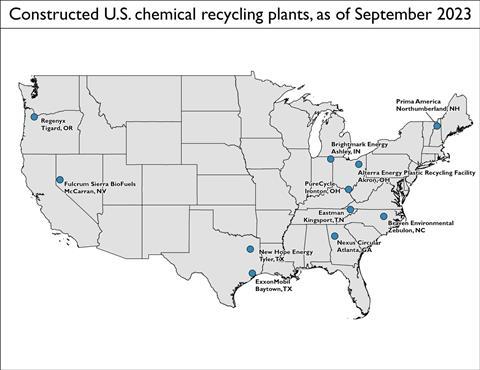

The new report examined the 11 chemical recycling facilities that exist in the US, looking at their contribution to environmental pollution. Its authors claim that chemical recycling processes insignificant amounts of plastic waste, and rarely yields recycled plastic. Their analysis also revealed that at least eight of these 11 facilities produce low quality fossil fuels.

However, many of these chemical recycling plants aren’t fully operational yet. The report concludes that if they were running at 100% capacity they could handle about 417,000 tonnes of plastic annually – about 1.3% of the plastic waste generated in the US.

But at least four of these 11 plants are operating at a pilot or demonstration scale, and at least four are partially or intermittently operating, according to the report. Three exclusively make feedstocks for new plastics, three produce only fuels, and the rest make a combination of plastic feedstocks or fuels and/or chemicals, explained Judith Enck, the founder and president of Beyond Plastics and a former regional administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

‘Our research shows that chemical recycling is more of a marketing and lobbying tactic by … industry than an actual solution to the problem of plastic waste,’ Enck stated.

An industry tactic?

A separate report issued in September by the Nordic Council of Ministers found that in the best possible case scenario chemical recycling would only process about 3% of the world’s plastic waste by 2040. ‘That’s around 14 million tons, it’s a drop in the ocean compared to the hundreds of millions of tons that will be produced in 2040,’ said Lee Bell, lead author of the report and IPEN technical adviser.

The report is in many ways well-meaning, but it doesn’t capture the multiple facets of chemical recycling

Oana Luca, University of Colorado Boulder

The Beyond Plastics and IPEN analysis also concludes that chemical recycling contributes to climate change and is inefficient. Earlier this year an analysis from researchers in Colorado found that chemical recycling can create as much as 100 times more damaging climate and environmental impacts than existing virgin plastic production.

Further, the new report’s authors also suggest that industry secrecy makes it extremely difficult to determine the actual cost of chemical recycling, as well as the public health or environmental impact. Specifically, eight of the 11 US facilities have no publicly available data about how much feedstock they have processed, and 10 of them have not disclosed data on what types and amounts of products they have created, according to Jennifer Congdon, deputy director of Beyond Plastics and one of the report’s contributors.

Oana Luca, a chemist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was part of a team that recently developed a new way to chemically recycle polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastics1, agrees that the pilot scale plants are ‘not yet putting a dent in the issue of plastic waste’. But she notes that a chemical recycling process can’t be assessed until it is scaled up and life-cycle assessments are performed that include detailed studies of environmental impacts, as well as technoeconomic analyses.

Luca points to chemical recycling methods that use electricity and reagents with minimal environmental footprints, including her own work. ‘My research group specialises in this, and I think there is merit to continuing to pursue this line of inquiry,’ she states. ‘A lot of the work we do is rooted in the existing basic science for chemical recycling.’

Anne McNeil, a chemist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who was part of a team that developed a technique to untangle superabsorbent polymers in diapers and turn them into an adhesive2, is concerned that the report could harm vital research in such areas. She warns that the umbrella term ‘chemical recycling’ can be applied to anything that isn’t mechanical recycling and potentially covers too many different activities.

Troublesome terminology

McNeil specifically uses ‘chemical recycling’ to refer to transformations that convert waste plastics into another chemical product – such as a monomer or a polymer – that has value as a chemical product rather than as a fuel, for example.

‘Technically, pyrolysis and gasification and things like that are chemistry – they’re breaking bonds,’ she explains. ‘But … I’m actually talking about substitution reactions – well-defined and controlled chemical reactions.’ The new report largely focuses on pyrolysis because that’s the form of chemical recycling that’s primarily currently being portrayed as a solution by the plastic industry, she says.

‘If you just ban chemical recycling altogether … there might be some good chemistry in there that would get unintentionally banned because of the terminology,’ McNeil warns.

Her team’s lab-scale lifecycle assessment showed that the process they developed, and have since patented, produced fewer emissions and required less energy to make the adhesive from diapers versus a petroleum feedstock. ‘That might be something that could be commercialised and could be better overall for the planet,’ McNeil says.

The Beyond Plastics and IPEN report also concluded that chemical recycling often produces harmful byproducts. ‘We found that because plastics are made with toxic chemicals, particularly with toxic additives, the products and the waste that come from chemical recycling retain these chemicals and when released these chemicals pose threats to our health and to the environment,’ explained Bell. He said plastic waste that is collected for chemical recycling will mostly emerge from the process as either hazardous waste, emissions or contaminated oils that require significant energy and cleanup to make them suitable for plastic production.

Hazardous waste generators

Four of the 11 US facilities are registered with the EPA as generators of hazardous waste, and two others have their chemical recycling processes embedded in a larger facility classified as a significant generator of hazardous waste, according to the analysis.

Although Luca concurs that some of the chemistries deployed for the purpose of chemical recycling involve ‘noxious energy-intensive reagents and steps’, she warns that writing off chemical recycling entirely is unwise. ‘The report is in many ways well-meaning, but it doesn’t capture the multiple facets of chemical recycling and the different kinds of chemistries used,’ Luca states.

In addition, she notes that most chemical plants would use advanced methods to ensure the safety of the recycling process, including careful thermal and hazard management to capture, neutralise and dispose of hazardous side products. Without more details about these safeguards, she says that it is difficult to conclude whether chemical recycling often produces harmful substances as byproducts and releases dangerous chemicals into the environment.

McNeil says she hadn’t understood how much hazardous waste is generated by chemical recycling before reading the report. ‘I just didn’t realise the volume of waste relative to the volume of productive stuff that comes out of there … it has changed my perspective quite a bit, assuming that I can take everything at face value,’ she says. ‘I used to think waste-to-energy was better than nothing, and now I’m more on the side of let’s landfill it.’

Besides calling for a national moratorium on new chemical recycling plants, Beyond Plastics and IPEN are also recommending several other actions at the US federal and state levels, including mandatory testing of outputs from chemical recycling before they can be used as fuel or plastic feedstock to prevent widespread contamination of products and human exposure to unacceptable toxic risks.

Meanwhile, the chemical and plastics industry is pushing back. Ross Eisenberg, president of America’s Plastic Makers, part of the American Chemistry Council, notes that researchers at the Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory recently found that chemical recycling significantly reduced greenhouse gas emissions and water use, compared with virgin plastics production. ‘Chemical recycling is expanding in use across many parts of the globe and being deployed to help build a more sustainable and lower carbon future,’ Eisenberg tells Chemistry World.

McNeil hopes that the plastics industry will read the report, debate its findings and conclusions, and take action to either improve chemical recycling or invest in different processes. ‘The experiment needed to be done, but maybe should be stopped immediately and then move on to the next experiment,’ she says. ‘And I want the pressure to remain on the plastics industry to come up with solutions because they definitely made this problem and continue to profit from it.’

References

1 P Pham et al,Chem Catalysis, 2023, DOI: 10.1016/j.checat.2023.100675

2 PT Chazovachii et al,Nat. Commun., 2021, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-24488-9

No comments yet