Chemistry combined with AI has been used to detect chemical signs of life in ancient rocks up to 3.3 billion years old. The approach could enable scientists to unlock previously inaccessible biomolecular secrets from rocks older than 1.7 billion years old, helping to unravel the mysteries of life’s origins and the evolution of its biochemical processes, including photosynthesis, as well as aid the search for extraterrestrial life.

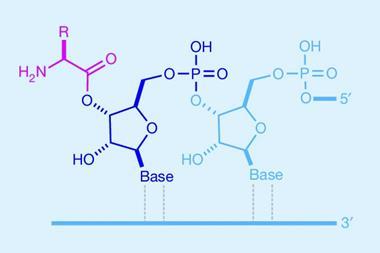

Ancient microfossils and isotopic signatures of carbon point to the earliest life on Earth forming around 3.45 billion years ago. Conversely, there is scant biochemical evidence of life preserved in ancient rock that has survived billions of years of geological processes. The earliest unambiguous records of complex biomolecules such as lipids and porphyrins – involved in compartmentalising early chemistry and metabolic pathways, respectively – stem from around 1.7 billion years ago, leaving a huge gap in the biochemical record spanning half of life’s known existence.

Now, an international team has tried to plug this gap by turning to analytical chemistry and machine learning to tease out biosignatures from rocks far more ancient than 1.7 billion years old. ‘Unlike any previous work, we are not looking for specific biomolecules like lipids or sterols,’ explains Robert Hazen at the Carnegie Institution for Science, US, who led the team. ‘Instead, we look for subtle hints in the distribution of all the little molecular fragments that result from decay of the original molecules.’

Biomolecular echoes

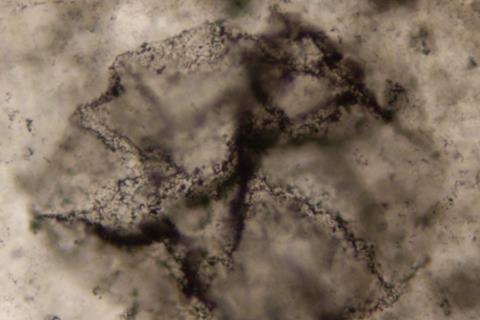

To do this, the team first obtained 406 diverse samples, most of which came from the collections of world-renowned palaeontologists. Samples included ancient sediments, fossils, modern plants, animals and fungi, and meteorites. The researchers then analysed them using pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. This effectively broke down both organic and inorganic materials contained within, releasing chemical fragments, akin to echoes of long deteriorated biomolecules.

The team then trained a machine learning model using around 75% of the samples to tease out patterns from the many chemical fragments and thus identify whether they had biological or non-biological origins, as well as determine whether they were produced by photosynthesis or not. The remaining 25% of samples were used to test how well it worked, revealing an accuracy ranging between 90% and 100%.

Among the results, the method identified that chemical fragments released from 3.3-billion-year-old sedimentary rock from South Africa were of biological origin but photosynthesis-linked molecules were not detected. Meanwhile, photosynthetic molecules were identified in another South African sample that was around 2.5 billion years old, extending the chemical record of photosynthesis by over 800 million years.

‘We were astonished [with that result],’ says Hazen. ‘You or I could never see the patterns in those fragments, but AI can. It’s the distribution of hundreds to thousands of fragments that tells the story of ancient life. My dream is that this approach becomes a new standard approach in palaeobiology and astrobiology, because the exact same method can be used to look for life on Mars.’

‘The work seems extensive and well thought out. The machine learning methodology itself is not new, but the application to a geochemical system like this is quite novel,’ says Tanai Cardona, who investigates the origins of photosynthesis at Queen Mary University of London, UK. ‘The results themselves do not add a novel perspective on the evolution of photosynthesis but they show that the methodology can complement, and is in agreement with, other approaches.’

Cardona thinks it would be interesting to test a wider range of older samples from the Archean eon, that began 4 billion years ago. ‘In fact, they should test all the samples which are available, so as to attempt resolving when signatures for oxygenic photosynthesis appear convincingly for the first time,’ he says. ‘This will be challenging since in many environments all sorts of metabolisms occur at the same time and at the same place.’

Hazen says this is just the beginning. ‘We need thousands of diverse samples that are well documented. Several scientists have already contacted us offering valuable new samples from Australia, South Africa, Greenland and Canada,’ he says. ‘The more diverse samples, the better the result and the more attributes we can tease out – for example, different kinds of photosynthesis or prokaryotes versus eukaryotes. The opportunities going forward are huge.’

References

M L Wong et al, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 2025, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2514534122

No comments yet