Scientists have uncovered three nitriles in lab-made interstellar ice that could serve as new targets for astronomers searching for prebiotic chemistry in the depths of space.

Astrochemists have been interested in nitrile compounds for many years as they can undergo chemical reactions to produce amino acids and nucleobases. Various nitriles have been identified in carbonaceous meteorites, yet how they form under harsh interstellar conditions is unclear.

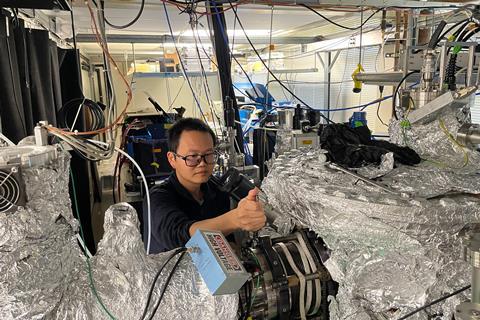

A popular technique for studying biorelevant molecules in simulated cosmic ices is Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, which provides information on functional groups. However, Ralf Kaiser, from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, US, and his colleagues wanted to find out the exact intermediates and isomers present, to understand what astrochemical pathways might be creating different nitrogen-bearing molecules.

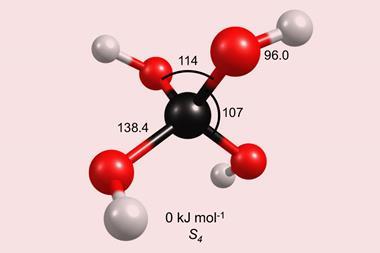

To do this, the team examined ices composed of hydrogen cyanide, which is known to be ubiquitous in the interstellar medium, using a combination of FTIR and isomer‑selective vacuum‑ultraviolet photoionisation reflectron time‑of‑flight mass spectrometry (PI‑ReToF‑MS). The ices, held at 10K to replicate ultracold interstellar conditions, were bombarded with energetic electrons to mimic galactic cosmic rays, and the resulting sublimed products were subsequently identified via PI ReTOF‑MS.

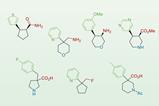

These conditions generated a suite of biorelevant nitrile compounds: ammonia, diazene, methylamine, ammonium cyanide, ethanimine, isocyanogen, cyanamide, iminoacetonitrile, N-cyanomethanimine and methyl cyanamide. The findings suggest these nitriles are plausible precursors to fundamental biomolecules such as glycine, adenine and guanine. Three of the nitriles – diazene, ammonium cyanide and methyl cyanamide – have so far not been detected in extraterrestrial environments, giving astronomers new species to hunt for with radio telescopes such as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (Alma) in Chile.

Astrochemist Cornelia Meinert, from University Côte d’Azur in France and a past collaborator of Kaiser, says that carrying out these experiments at interstellar temperatures is a ‘huge advantage of this ionisation strategy’. At higher temperatures, she notes, radicals become more mobile and can trigger reaction pathways that wouldn’t occur in real interstellar conditions. Conducting PI-ReToF-MS at interstellar temperatures therefore gives the team much more realistic results.

As ices are present throughout the galaxy, ‘the reactions we are investigating have a wide application beyond our solar system,’ notes Kaiser. He says their findings will help researchers predict where biomolecules and life might be uncovered.

Correction: This story was updated on 2 February 2026 to fix an error in the experimental description

No comments yet