The Stockholm Declaration on the Future of Chemistry that was recently unveiled implores chemists to build a just, sustainable and resilient world for current and future generations. It was drafted by chemists and engineers invited to speak at a Nobel Foundation symposium on sustainability.

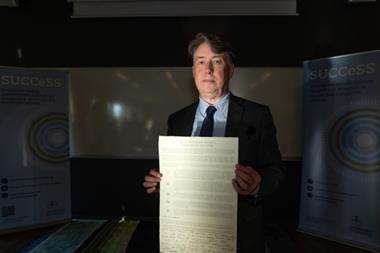

The declaration was unveiled and signed at the Nobel Symposium on Chemistry for Sustainability, organised and hosted by the Stockholm University Center for Circular and Sustainable Systems. Spearheaded by Paul Anastas, a chemist at Yale University and co-author of the 12 principles of green chemistry in 1998, the declaration contains five central themes. These are taking immediate action, ensuring chemical products and processes do no harm to people or the planet, training the next generation of chemists to prioritise sustainability and health, ensure open access to chemical data and information, and align government policies on chemistry with sustainability and public health.

For the drafters, the response has been incredible. ‘Within the first week, I think we’ll probably have close to 1000 signatories,’ says Anastas. ‘That is far beyond anything I could have imagined.’

There are currently over 900 signatories, including several Nobel laureates. The German Chemical Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Indian Chemical Society and the Australian Chemical Society have also formally acknowledged and adopted it. ‘I would have thought that that would have taken many months of deliberation,’ says Anastas, ‘so I’m shocked.’

Kylie Luska, a chemist at the University of Toronto and instructor for the institute’s Focus on Green Chemistry programme, was motivated to sign in part by the education theme. For him, education is an important part of green chemistry because future chemists need training in topics like toxicology to better understand the impact of their work, but also to change attitudes on sustainability. ‘I think this is why education and its note in the declaration are so important,’ he says. ‘We need to change that mindset, so these students aren’t thinking about sustainability as a secondary item, but they’re thinking about it right at the beginning.’

Peter Licence, head of chemistry at the University of Nottingham and one of the declaration’s drafters, says education is a subtle but important part of the document because of its reach. ‘We don’t just educate people that are going to make molecules,’ Licence says. ‘We educate people that are going to turn into patent attorneys, that are going to turn into accountants, that are going to turn into decision makers, they’re going to turn into logistics experts. And if they understand the challenges, and if they understand the opportunities, then that impact is huge,’ he says.

While optimistic Licence, who is also director of the GlaxoSmithKline Carbon Neutral Laboratory, is also frustrated at the lack of wider implementation of green chemistry innovation over the past 25 years. ‘We must do it now, because if we leave it much later, it’s going to be too late,’ he says.

‘The only way to appropriately support all of the brilliant science and technology that’s been discovered is to implement it,’ Anastas says. Importantly, though, Anasatas says the declaration is not about what chemistry can’t do or must ban. ‘This is about what we can create, what we can invent, what we can innovate.’

No comments yet