Scientists in Canada have developed a paper-based device that checks if bacteria are resistant to certain antibiotics. The simple system could help users in remote areas pick the most appropriate treatment for bacterial infections.

Testing bacteria to see which antibiotics will be effective against them is vital for properly medicating patients. Methods exist to assess bacteria but the equipment needed is often expensive and requires highly trained operators and laboratory conditions. Now, Ratmir Derda and colleagues at the University of Alberta have designed a portable device made from paper and other low-cost materials. The team sought the help of high school students to make and test the devices to show how easy they are to construct and use.

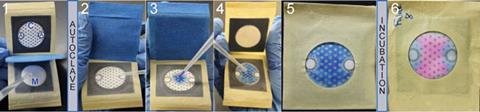

Derda’s device consists of a paper support with a clear plastic window over an area of nutritious media permeated into a sheet of thick blotting paper. This culture media has a uniform pattern of hydrophobic spots to ensure samples disperse evenly across it. Two zones of antibiotics are added onto the media before the device is sterilised in an autoclave. After autoclaving, a cell viability dye is dropped on the culture media and the bacterial sample is then added on top of the dye. Finally, the device is sealed and incubated overnight.

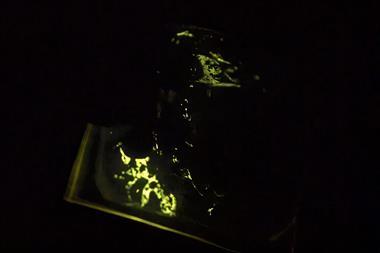

In areas with no bacterial growth the dye remains blue and in areas where bacteria do grow the dye turns pink. The colours are easy to see through the device’s plastic window – there is no need to open the device. A blue area around the antibiotic zones indicates that the bacteria are susceptible to the antibiotics. The hydrophobic spots on the culture media aid quantification of the blue area to give an idea of how sensitive the bacteria are to the antibiotics.

‘This work shows that living microorganisms can be grown and screened for antibiotic resistance using paper devices that are small and light enough to store in a person’s pocket,’ says Marya Lieberman, an expert in paper-based sensors at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, US.

The team also found that the device could easily be stored long-term. After assembling to the point that it contained the culture media and antibiotics, it could be left for up to 70 days in a sealed bag. This storage ability along with the device’s cheap components and ease of use make it very promising for use in remote areas.

No comments yet