Peer review by live blogging

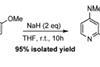

A controversial paper suggesting a strong reducing agent can promote oxidation was rapidly tested in the blogosphere

A controversial paper suggesting a strong reducing agent can promote oxidation was rapidly tested in the blogosphere