US chemists have reproduced a 90-year old experiment to settle a 50-year old controversy

Two organic chemists claim to have settled a major dispute over the first synthesis of quinine by revisiting an experiment performed over 90 years ago.

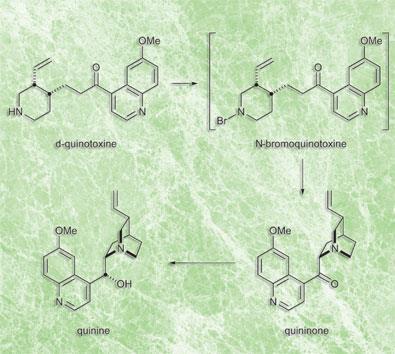

Aaron Smith and Robert Williams from Colorado State University, US, have reproduced a three-step conversion of d-quinotoxine into quinine [1] first performed by chemists Paul Rabe and Karl Kindler in 1918 [2] that was referenced but - crucially - not carried out in the first published total synthesis of the compound.

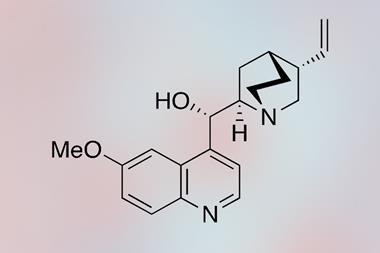

The controversy dates back to 1944, when two rising stars at Harvard University - Robert Burns Woodward and William von Eggers Doering - claimed to have come up with the first total synthesis of quinine [3], an alkaloid with impressive antimalarial properties that occurs naturally in the bark of the Cinchona tree.

The report of quinine’s total synthesis caused a sensation, not least because many of the natural sources of quinine were in the Dutch East Indies (modern day Indonesia), which were then in enemy hands. The hope - never realised - was that Woodward and Doering’s quinine synthesis could be scaled up to help fight malaria on the battlefield.

But, despite press reports at the time, Woodward and Doering had not actually produced quinine. Instead, their 17 step synthesis ended with d-quinotoxine and they referred to Rabe and Kindler’s 1918 work to demonstrate that total synthesis of the compound was possible.

That led to doubts over the validity of their pathway and controversy over Woodward and Doering’s claim has continued ever since.

Competing claims

Perhaps their most vocal critic has been Gilbert Stork, based at the University of Wisconsin and then Harvard, who had also begun work on his own total synthesis of the compound in the 1940s.

In 2001, when Stork and his colleagues published their own synthesis of quinine via a completely different route [4], he was quoted as saying that had Woodward and Doering attempted the Rabe-Kindler conversion, it ’would not have worked’ [5]. The implication was that their synthesis was no synthesis at all.

Now, after 90 years, Smith and Williams have published their attempts to replicate the Rabe and Kindler conversion and say that this should, at last, remove any blemish on the reputations of Rabe, Kindler, Woodward and Doering. ’Stork has done a major injustice to their work,’ Williams said. ’We’ve proven that he’s dead wrong.’ The secret, they say, lies in the last step of the conversion.

In Rabe and Kindler’s 1918 paper, they first oxidised d-quinotoxine using sodium hypobromite to give N-bromoquinotoxine. The second step was base-mediated cyclization to produce quininone. Finally, quininone was reduced to quinine with aluminium powder.

’The first two steps worked perfectly,’ says Williams. However, the final reduction produced barely detectable quantities of quinine.

Purity problem

Smith and Williams hypothesized that the problem lay in the purity of their aluminium powder. ’It would have been kept in a stoppered apothecary jar open to the air,’ says Williams. Replicating these conditions by exposing their elemental aluminium to oxygen, the final step of the conversion went ahead smoothly. ’We’re 100 per cent sure that had Woodward and Doering been motivated to convert their d-quinotoxine to quinine, they would have succeeded,’ says Williams.

’This has closed the door on any doubts,’ says Jeffrey I. Seeman, an expert on alkaloids at the University of Richmond, Virginia and a historian of chemistry. Seeman recently reconstructed the ins and outs of this controversy in an article published last year [6]. ’My historical research provides much evidence that Rabe and Kindler did, in fact, convert d-quinotoxine to quinine,’ he says.

Woodward and Doering set as their target the preparation of d-quinotoxine from 7-hydroxyisoquinoline, says Seeman, relying on the Rabe-Kindler conversion to do the rest. ’Smith and Williams’ experimental evidence unambiguously and conclusively established the validity of Rabe and Kindler’s 1918 work and, in consequence, the validity of the Woodward-Doering/Rabe Kindler total synthesis of quinine,’ he says.

But why did Woodward and Doering not go on to complete the synthesis of quinine themselves? Stork, now emeritus professor at Columbia University, suggests the pair knew that the attempt was likely to end badly - either failing because of a lack of detail in the original Rabe and Kindler method, or by producing an unimpressively low yield of quinine. ’Why should they sully their superb synthesis of "homomeroquinene" by advertising that fact?’ Stork told Chemistry World.

’The problem was that Woodward and Doering were immediately caught in a whirlwind of hype by the media (creating the myth of feasible large scale synthesis) because of the enormous relief felt that we now had a solution to the critical quinine shortage during the US World War II operations in Asia,’ he added.

Henry Nicholls

References

1 A C Smith and R M Williams, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, DOI:10.1002/anie.200705421 2 P Rabe and K Kindler, Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges., 1918, 51 3 R B Woodward and W E Doering, J. Am. Chem. Soc.664 G Stork et alJ. Am. Chem. Soc.1235 M Rouhi, Chem. Eng. News796 J I Seeman,

No comments yet