The head of the US’s environment agency is on a collision course with his own staff over science

What does chemistry have to do with American politics? When it comes to the embattled head of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the answer is plenty.

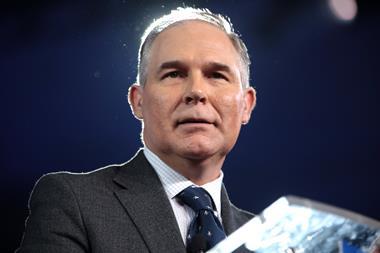

In recent months, Scott Pruitt has been caught up in scandals involving luxury travel, a sweetheart condo rental deal from a well-known lobbyist and the purchase of a $43,000 (£32,000) soundproof phone booth with public funds. That’s on top of accusations that he’s anti-science.

Most recently, leaked emails suggested that the EPA aimed to stop another agency from publishing its analysis of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS). This report suggested that PFOA and PFOS are harmful at lower levels than EPA drinking water limits. In an email forwarded to the EPA earlier this year, a White House staffer warned the numbers could create a ‘public relations nightmare’.

When asked about these allegations, Pruitt said he was unaware any details were held back. While he agreed the EPA should set legal limits for PFOA and PFOS that go beyond advisory status, Pruitt also declared: ‘What is most important to me is not just studies.’ This is significant in light of the US PFOA and PFOS water contamination crisis, and Pruitt has announced that EPA will evaluate if a maximum limit is needed for the two chemicals. Clearly, such health and environmental rules should be grounded in ‘just studies’.

The scientific community’s concerns about Pruitt go beyond fluorinated chemicals. There are also worries about a new rule he has proposed that requires all data used to inform EPA guidance be publicly available, and forbids using studies that cannot meet this requirement. Science advocates aren’t buying Pruitt’s assurances that the change will make EPA’s regulatory decisions easier to publicly and independently verify. They fear the rule will hamper EPA research to set regulations because the data from many public health studies cannot be so disclosed, and aren’t replicable without deliberately and illegally exposing people to harmful pollutants.

Even members of the EPA’s own science advisory board have criticised Pruitt’s plan, saying it ‘appears to have been developed without a public process for soliciting input from the scientific community’. Key posts at the EPA are still vacant, and if the EPA wants to attract high calibre scientists then its leader must show he values what they do.

No comments yet