The UK is facing a drought. I’m not talking about the paucity of rainfall this summer but the way in which undergraduate chemistry provision across the country is starting to dry up. With cash-strapped universities discontinuing courses or closing departments altogether, new chemistry ‘deserts’ are now opening up across the UK – areas where the nearest institute teaching the subject is over an hour’s drive away. This development could worsen the problem of falling numbers of chemistry students and hit the poorest in society hardest.

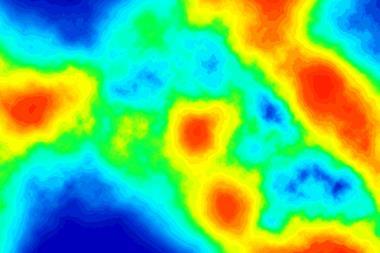

The causes of higher education’s financial problems are multi-faceted but what matters is that chemistry departments – as one of the most expensive subjects thanks to their teaching commitments and labs – have been squeezed hard. This has led to closures of chemistry departments such as those at Hull and Bangor that have left would-be chemistry students in the Humber and East Yorkshire and in North Wales with no local provision. The financial pressures that precipitated these tough decisions by universities haven’t gone away and further course and departmental closures in chemistry are a distinct possibility in the coming years, threatening further desertification.

The students who will miss out as chemistry becomes concentrated in fewer institutions will be the poorest. A 2018 report from the Sutton Trust found that a quarter of students were living at their family home a short commute from their university. However, the poorest students were around three times more likely to be living at home (45%) than the wealthiest (13%), as the cost of accommodation puts moving further away beyond the reach of many. The harder it becomes for students from lower socio-economic backgrounds to stay at home while studying chemistry, the less likely it is that they will choose to study it.

If those students are deprived of the opportunity to pursue chemistry, then the field as a whole is deprived of a large pool of potential talent. This would be a loss to the field at a time when the Royal Society of Chemistry is projecting that chemistry jobs are set to grow faster than those in other sectors. Providing an even geographic spread of chemistry provision is exceptionally difficult – if not practically impossible. At this stage, the problem of chemistry deserts or ‘cold spots’ is being identified, and that is the first step to tackling this important issue.

No comments yet