Outmoded, capricious and burdened with obligations – so why does everybody want one?

When recently I took part in one of those discussion panels that convene around Nobel time to discuss who will win this year’s gongs, I rooted for the late Mildred Dresselhaus, along with Sumio Iijima, for their ground-breaking work on nanocarbon. Why? Well, the field – especially as far as carbon nanotubes are concerned – has been central to conceptions of nanotechnology; has had useful practical applications; has transformed our notion of the literal shape of chemistry (for nanotubes, molecular in two dimensions while macroscopic in the third); and…

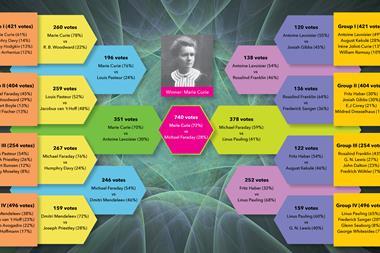

But wait; we know this already. I suspect everyone whose opinion counts already recognises the value of what these two (and a host of others) have achieved in the area. Nobels obviously matter to those who get them, although I wouldn’t take it for granted that all laureates are overjoyed given the burden of obligations it tends to impose. For the rest of us, nominating candidates is a bit like wanting the world to share our love of a particular novel or band, and there’s surely some element here of wanting to have our good taste vindicated (I felt that vindication sure enough with last year’s award). We have, too, a sense that justice should be done, especially when we fear time is running out – as it was for Dresselhaus (who died in February), and as it is for perennial nominee favourite John Goodenough, a pioneer of materials for lithium battery technology and 95 this year.

‘Not chemistry’

A desire for validation also lies behind some of the grumbles, now almost routine in chemistry, that the Nobel has been awarded yet again outside the discipline, most often to molecular biology (although 2011 laureate Dan Shechtman, discoverer of quasicrystals, is considered by some too much a ‘materials scientist’).

The usual response, and I think a correct one, is that these choices show just how broad chemistry is. Nobel laureate Roald Hoffmann puts a different slant on that,1 saying that it was a mistake that ‘for reasons buried in history and personalities, about a hundred years ago we allowed the biological to get away from chemistry’. Indeed, around the end of the 19th century the ‘secret of life’ was thought to be a question of chemical composition – and then later of molecular organisation (which is nearer the truth). When James Watson and Francis Crick exclaimed to a crowded pub in 1953 (perhaps apocryphally) that they’d discovered that ‘secret’ after deducing the structure of DNA, there is really no question that it was a discovery in chemistry. Similarly, the ‘chemical turn’ that Hoffmann identifies in modern biology is echoed by that in today’s materials science.

But the danger here is a descent into disciplinary turf wars, which I know is the last thing Hoffmann wants. What it really means is that our 19th century map of scientific boundaries is of doubtful relevance. Any carving up of knowledge about the physical world is an artificial process necessitated for institutional convenience, which we shouldn’t mistake for a law of nature. The Nobel prizes are obliged to honour their founder’s increasingly outmoded categories, but we should really see them and treat them as prizes for science as a whole, with loose constraints imposed to encourage an even spread. There must be more inventive ways to bring, say, the earth sciences and palaeontology (currently showing immense vitality) under that umbrella.

Dreams and desires

Some feel that the Nobels exert a pernicious effect. Hoffmann is right that there are many more deserving recipients than there can ever be winners, so some caprice is inevitable. The magnitude of the accolade can distort priorities and incentives – many of us will know individuals tortured by the desire. (It was rumoured that the unavailability of one of my university tutors was because he was working flat out for the prize, which the poor man never got.)

And if it comes, the prize doesn’t seem to make some recipients any happier (or nicer, or indeed saner); it encourages a false and sometimes dangerous public perception that they have become a fount of all knowledge, which a handful of laureates start to believe themselves. Most are wiser.

Yet Hoffmann argues that the prizes have value in motivating young people to take up science and work hard at it: they are a dream machine, offering rewards available to anyone on merit. A dream machine itself has debatable virtue, because not everyone wins – but the important thing, Hoffmann says, is that you realise once you’ve got serious about your science how little winning matters. Of course, that’s the hard bit.

This motivational aspect was also a big factor in why I rooted for Millie: I know from having daughters that seeing women celebrated in science makes a difference, and for the same reason I know how important role models of one’s own ethnicity are. Instinctively, I want such awards to be blind to gender, race, and all other distinctions we make between people. But the outcome influences how well, or not, society uses its intellectual resources – and we should all care about that.

References

1 R Hoffmann, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 1734 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201108514)

No comments yet