How we compare science superstars leads to important questions for chemistry

Everyone wants to know who’s the best. Human achievement is built on league tables and rankings, healthy competition or historic inspiration. We like to pretend that we don’t really care about anyone else, but our entire way of life is built on superlatives. We want to know the biggest, the fastest, the most important. It’s a way to see how we’re stacking up, a way to motivate ourselves and learn how to improve. And when it comes to the elite group of humans who have left a lasting legacy, it’s also fun to put their contributions in context. Ranking them helps us remember what has come before, organises our minds to look at the greater picture, and rekindles inspiration with tales of heroes and villains.

That’s why, in early November, I decided to hold a competition on Twitter to pick the greatest chemist of all time. It was supposed to be just a bit of fun; greatness, after all, is pretty hard to define – it’s just a vague concept of being a little bit better than ‘pretty good’. Somehow, it spiralled into something a bit more than that.

What makes someone great

The how was easy: a tournament using Twitter polls, with group stages and rounds. All I needed were contenders – and that provided the first roadblock. What, exactly, was I basing greatness on? For sports teams, at least there’s some quantifiable measure. You can look at hit percentages, speed of bowling, goals scored or championships won. But even then there are the intangibles – those little gems of brilliance that fall outside of mere statistics – and the problem of comparing across eras, positions or classes. Was Babe Ruth better than Barry Bonds? Could Lionel Messi dribble past Pelé in his prime? Would Muhammad Ali have beaten Floyd Mayweather? You could have the debates for hours.

It’s worse in science. There’s no accessible way to compare disciplines, so all you can do is think of the most famous chemists you can and go from there.

A few names were obvious from the start: chemistry’s household names like Marie Curie, Michael Faraday and Humphry Davy. Their greatness was not just the sum of their (impressive) achievements, but a kind of immortality. For the same reason, I included Glenn Seaborg; not a household name, but a scientist whose discovery of plutonium and other elements led to him having element 106 named after him. He might not be as known as Davy, but as long as we have science, seaborgium will live on.

Next, I drew up a list of people on achievement – founders of scientific disciplines or people whose work is still applied today. This included the likes of Irène Joliot-Curie, Gilbert Newton Lewis and the wonderfully named Jacobus van ‘t Hoff. Their greatness seemed to be defined by professional admiration: respect within the confines of science.

There was another factor at play, too: legacy. Many of the names were associated with each other, greatness fuelling and inspiring a successor who went on to fame and success. Seaborg studied under Lewis; Faraday under Davy; Joliot-Curie was Curie’s daughter. I didn’t know if great minds were drawn to each other, or if I was also measuring an ability to find and nurture talent.

I kept adding. The founders of science went in. Modern scientists who are touted as the greatest of our day were included. Largely forgotten names that paved the way were added. Finally, I left eight slots as ‘wildcards’ and opened them up to the public. And here’s where the trouble began.

Checking privilege

Names flooded in thick and fast – so fast it was impossible to include them all. Tough decisions had to be made. Did I include the likes of Jacob Berzelius, an 18th century Swedish chemist, or Roald Hoffmann, a modern maverick still teasing students at Cornell? To keep the list to 32 I had to make some tough choices, making my own arbitrary judgments about someone’s level of chemistry prowess.

But another problem emerged: where, people demanded, were all the women? And why was there no people of colour on the list?

This exposed an early flaw in judging greatness. The truth is that for 200 years, chemistry (along with pretty much everything else) has been dominated by European men. Anyone else was largely shut out – and those barriers still exist today. The names were absent because I was judging greatness based on recognised achievements; as many pointed out, perhaps I should have been considering what people did despite the environment they faced and the obstacles they overcame. More women were added to the competition (five in all) though it still felt like it was inadequate.

Devils in angel clothes

The final problem was the calls for some of the names to be stricken from the contest. A few argued that the names weren’t chemists – a scientific tribalism that doesn’t help anyone – and pushed for Faraday to be condemned as a physicist or Pasteur to be booted out on suspicion of being a filthy biologist. In the end, I only made one such call: Ernest Rutherford was rejected as a chemist, purely because he used to storm around 1930s Cambridge insisting that he wasn’t.

The other issue was how to balance a person’s great achievements with their terrible ones. There were immediate calls for Fritz Haber – a chemist who invented a method to synthesise ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen – to be thrown out. Haber’s discovery led to fertilisers that currently feed half the known world: an unquestionably great achievement. The problem was he also invented chemical warfare. In the end, Haber remained: it would be up to the public vote as to whether an invention that saved billions of lives outweighed creating one of the deadliest weapons of the modern age.

So who won?

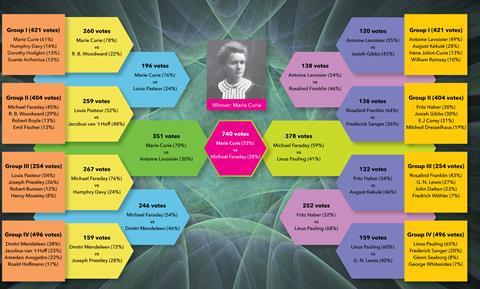

The vote progressed over two weeks in a series of daily votes on Twitter, whipping the chemistry community into a flurry of discussion about its legendary figures. Debates raged on social media, as chemists championed their favourites. A few unlikely names emerged with cult followings as journalists from Nature got behind Team van ‘t Hoff and Team Lewis to pull them through the heats; two-time Nobel prize winners were dismissed for some kooky beliefs in later life; the Royal Institution joined in the fun as its two heroes Humphry Davy and Michael Faraday found themselves pitted against each other in the semi-final.

Faraday prevailed in that fixture, only to find himself matched against Marie Curie, who had sailed through all of her matches comfortably. The result was apparent within minutes of the poll launching: after 6320 votes across the competition, Marie Curie won by a landslide.

Marie Curie. A scientist who, like Albert Einstein or Stephen Hawking, is a household name. A chemist whose achievements (coining ‘radioactivity’, discovering two elements, winning two Nobel prizes, saving thousands in the first world war with mobile x-ray machines, having an element named after her) are unquestionably great. A mother who created a scientific legacy that saw her daughter win the Nobel prize. And a woman who fought through barriers of sexism and prejudice to become recognised, even in her own time, as one of the most brilliant stars in the scientific heavens.

By every measure I, or anyone else, could come up with for a winner, Marie Curie met the criteria. Perhaps defining the greatest chemist of all time isn’t such a tricky proposition after all…

Everyone wants to know who’s the best. Human achievement is built on league tables and rankings, healthy competition or historic inspiration. We like to pretend that we don’t really care about anyone else, but our entire way of life is built on superlatives. We want to know the biggest, the fastest, the most important. It’s a way to see how we’re stacking up, a way to motivate ourselves and learn how to improve.

That’s why, in early November, I decided to hold a competition on Twitter to pick the greatest chemist of all time, a battle between 32 amazing chemists. A few names were obvious from the start: chemistry’s household names like Marie Curie, Michael Faraday and Humphry Davy. Next, I drew up a list of people on achievement – founders of scientific disciplines or people whose work is still applied today. Then I threw in legacy, the people who built a scientific dynasty that echoed through the ages. Things got sticky defining ‘chemist’ (do you count Louis Pasteur?) and there were calls for Fritz Haber, whose discoveries led to fertilisers that currently feed half the known world but, awkwardly, invented chemical warfare.

Another problem also emerged: where were all the women? And why was there no people of colour on the list? This exposed an early flaw in judging greatness. The truth is that for 200 years, chemistry (along with pretty much everything else) has been dominated by European men. Anyone else was largely shut out – and those barriers still exist today. The names were absent because I was judging greatness based on recognised achievements; as many pointed out, perhaps I should have been considering what people did despite the environment they faced and the obstacles they overcame.

After some 6320 votes, debates and general nerdiness, eventually a winner was crowned. Marie Curie won by a landslide.

Curie. A scientist who, like Albert Einstein or Stephen Hawking, is a household name. A chemist whose achievements (coining ‘radioactivity’, discovering two elements, winning two Nobel prizes, saving thousands in the first world war with mobile x-ray machines, having an element named after her) are unquestionably great. A mother who created a scientific legacy that saw her daughter win the Nobel prize. And a woman who fought through barriers of sexism and prejudice to become recognised, even in her own time, as one of the most brilliant stars in the scientific heavens.

By every measure I, or anyone else, could come up with for a winner, Marie Curie met the criteria. Perhaps defining the greatest chemist of all time isn’t such a tricky proposition after all…

No comments yet