Flash, blast and radiation – is it possible to live through a catastrophe?

I got my PhD in chemistry from Imperial College London in the UK at about the time of the Cuban missile crisis. ‘Just my luck!’ I thought. ‘I’ll be shaking the hand of the Queen Mother in the Albert Hall when Khruschev drops the bomb on it!’ In those days I spent much of my time in London doing my research, and also some out in Orpington, a suburb of London where my parents lived.

Looking back, I am amazed at how ingrained and widespread was the social fear of sudden nuclear war. London was certain to be bombed. My particular fear was to be travelling on the London Underground when the bomb fell. The train might be too deep for the effects of the blast to reach it – but the electricity would fail, the lights would go out, and I would be trapped in the dark in a huge crowd of desperate people, to die slowly of hunger, thirst or suffocation. As a chemist, I was able to make up potassium cyanide tablets against this fate, which I carried around in my pocket.

We discussed the options in the laboratory. If I was in Orpington, I had a chance. A nuclear bomb generates an extremely bright flash, which may last for several seconds. So wear an eye patch! Even if you were looking that way when the bomb went off, you could move it over. And get out of the building at once! It may protect you from that flash, but the blast, when it comes, will knock the heavy structure down on you.

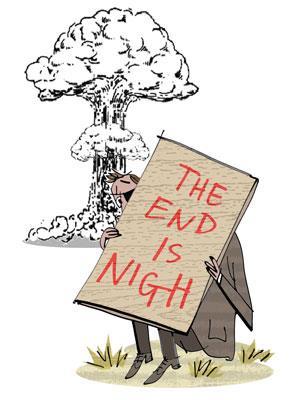

When you are outside, or if you are already outside when you see the flash, run to any kind of flimsy flash protection such as a wooden fence. It will probably catch fire or already be on fire, but will at least intercept the flash. (In the laboratory, we liked the idea of a plywood sandwich board, possibly proclaiming ‘The End is Nigh’, behind which you could duck when the flash came). If the blast comes while the flash is still bright; you are too close, and doomed anyway. But if the flash fades first, dash out from your flimsy shelter, and lie in the open face-down with your head towards the growing mushroom cloud. With luck, you’ll survive the coming blast.

If you do survive the flash and blast, you have just a few hours before the radioactive dust starts to come down. You have to be quite ruthless; and you need a car. First, you must get water from the taps while they still work – I planned to fill a couple of big empty acetone cans I had. Then you must get lots of tinned food, a tin opener, a portable radio, and Polaroid film which will allow you to measure the amount of radioactivity in the environment. Finally you have to hide somewhere away from the radioactivity – I had in mind some abandoned boilers I had spotted near Orpington hospital. A metal boiler would exclude a lot of radioactivity. I could plug up any holes, and it was unlikely anyone would look in one for a survivor. From the noises coming from the hospital I could perhaps judge how society was going.

When the Polaroid film showed that the radioactivity had largely decayed, I would come out. What life would be like, and whether it would be worth living, was something we did not discuss in the laboratory. In the event, mercifully, we never had to find out.

No comments yet