A potential legal battle over weight-loss medicines between Novo Nordisk and US compounding pharmacy Hims & Hers has been headed off, helped by intervention from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Novo won US approval for a tablet version of Wegovy (semaglutide) in December – essentially a higher-dose version of its already-approved diabetes pill Rybelsus – aiming to get ahead of several other oral GLP-1 drugs that are advancing through clinical trials. Novo began marketing Wegovy tablets in January, at a significantly lower price than the injectable form of the drug. In early February, Hims & Hers said it would offer a discounted version of the pill – Novo immediately threatened legal action, claiming patent infringement.

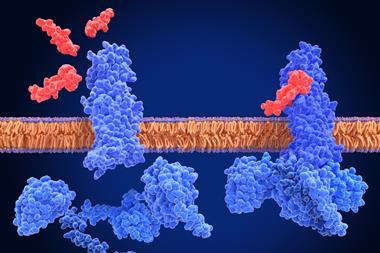

Since the introduction of Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) and then Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound), both companies have locked horns with US compounding pharmacies and wellness clinics that have produced their own versions of the drugs to corner a slice of this lucrative market.

Compounders can legitimately produce bespoke versions of drugs for specific patients whose needs are not met by approved formulations, or when drugs are in short supply. Both Novo and Lilly experienced delays ramping up manufacturing for their injectables, giving compounders an opportunity to meet the demand. Once the companies’ supplies improved, the compounders – especially larger ones like Hims & Hers – fought hard to justify continuing to supply their versions.

Within hours of Hims & Hers announcing its semaglutide pill, the FDA launched a crackdown on non-approved GLP-1 drugs – specifically mentioning Hims & Hers, among other compounders. The FDA does not directly regulate compounding pharmacies, and cannot prevent them from making compounded treatments to address legitimate needs. However, it can intervene if those companies don’t follow the rules on marketing their products, which proscribe saying compounded products are ‘generic versions’ or ‘the same as’ drugs approved by FDA, or that they use the same active ingredients, or that the products are ‘clinically proven’ to produce results. The FDA had previously warned several compounders over their marketing claims – including Hims & Hers’ high-profile advertisements at the 2025 Super Bowl. The compounder also advertised during the 2026 Super Bowl.

The following day, Hims & Hers withdrew its semaglutide pills from sale. However, given the size of the potential market for weight-loss drugs, it would be surprising if this is the end of this particular struggle.

No comments yet