Creativity nurtured by an explorative environment

Are you an optimist? It feels like a difficult thing to be as many of the geopolitical certainties of the past few decades dissolve before our eyes. Yet scientists cannot really be anything else. To embark on a research project is to imagine that the question can be answered and the problem has a solution.

But the mindset has its pitfalls. A recent preprint released on PsyArXiv suggests that scientists working on ‘sustainability’ problems like batteries and solar cells are more likely to think that science and technology alone will solve our energy and environmental problems. Some commentators have likened this to Charles Dickens’ lovable but infuriating character Mr Micawber, who cheerfully thinks that ‘something will turn up’ but without doing anything more than what he already does. By contrast, there are other optimists who seem to actively make their own luck, and whose optimism is part of a virtuous feedback loop.

Optimists often come in clusters, in which individuals synergistically extend the outlook and efforts of the other. One such cluster occurred at the General Electric (GE) Research Laboratory, founded in 1900 in Schenectady, upstate New York, US. Founder and director Willis Whitney hand-picked researchers and let them get on with fundamental studies, confident that they would find interesting things. Over a 20-year period the lab would come to be known as the House of Magic.

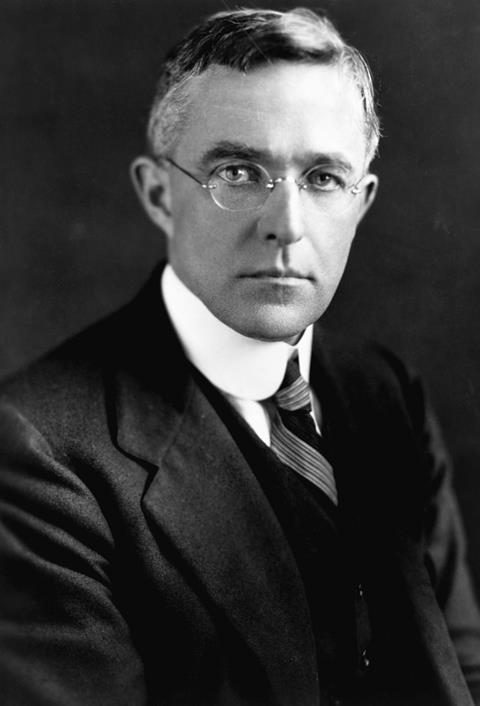

One of the key drivers of that innovation was Irving Langmuir, a figure so legendary that he even has a unit named after him. Born in Brooklyn in New York City, his father moved the family to Paris, France, for three years, a move that widened Langmuir’s horizons. His elder brother was a research chemist who set him up with a home lab and taught him maths and chemistry, which cemented his love of science. Langmuir studied metallurgical engineering at Columbia School of Mines and then went to Germany to do a doctorate with Walther Nernst, who set him the problem of understanding the dissociation of water and carbon dioxide around an incandescent filament. On the strength of his thesis, he was appointed to a teaching position at the Stevens Institute of Technology across the Hudson River from New York.

A lightbulb moment

In 1909 Langmuir secured a summer internship at the GE Research Laboratory, where he met William Coolidge, who had cracked the problem of drawing tungsten into wires. The wires were central to developing electric lighting, x-rays and, within a few years, the vacuum valves required for electronic devices. But the wires remained brittle, something that Langmuir suggested might be associated with occluded gas and impurities in the metal. He set about analysing this and the question of why the evacuated envelope of the lightbulbs tended to blacken rapidly.

Langmuir made a detailed study of the mechanism of heat loss from the wires and established the rate at which atoms sublimed from the filaments as a function of temperature. This led, in 1913, to a patent that would change the lighting industry. Langmuir suggested that having a highly evacuated bulb led inevitably to filament failure. The metal of an incandescent filament would gradually sublime away.

With carbon filaments, introducing nitrogen into the bulb led to the formation of cyanogen, which corroded the thread and caused brown deposits to appear on the bulb. With a tungsten filament, nitrides would form. Hydrogen was no good – not only was the thermal conductivity of the gas too great but Langmuir showed that it dissociated on the surface, further stealing away heat from the filament. Instead he proposed introducing argon into the bulb. Argon, discovered 25 years before by William Ramsay, was not only inert, but being heavy and monoatomic, its heat capacity was relatively low. Not only did the filaments last longer under these conditions but, with the gas present, convection would carry any metal that still sublimed to the top of the bulb, keeping most of the glass clear.

Cleaning up vacuums

Alongside this work, Langmuir quantified the rate at which incandescent tungsten wires scrubbed oxygen from the residual gas inside a lightbulb. Frederick Soddy in England had already demonstrated how calcium vapour could ‘absorb’ a variety of gases; Langmuir’s meticulous work set the stage for the science of gettering and the later invention of sublimation pumps, which would achieve truly extreme vacuums later in the century.

In these early days, Langmuir and his lab assistants were still pumping their systems using the mercury piston pumps developed by Heinrich Geissler and August Töpler. Wolfgang Gaede’s electric rotary pumps, which came onto the market in 1912, could only achieve vacuums around 10‑3 mbar. Then in 1915, Gaede published a description of what he called a diffusion pump, an elegant device where gas would diffuse through a slit into a fast moving ‘wind’ of mercury atoms that would sweep them away, evacuating the system. Although astonishingly simple, its pumping speed was very low.

But the paper triggered a series of connections in Langmuir’s mind. On a laboratory scale, a Bunsen pump or water aspirator could generate the modest vacuum required for filtration. Industrial installations used much more powerful steam ejectors, devices in which pressurised steam was blasted through a nozzle at supersonic speed, thereby entraining gas from a connected manifold. The speed of the blast (up to Mach 6) was such that back-diffusion was impossible. By placing several in series, it was possible to achieve pressures better than the new electric rotary pumps. Could one make an ejector that used mercury vapour?

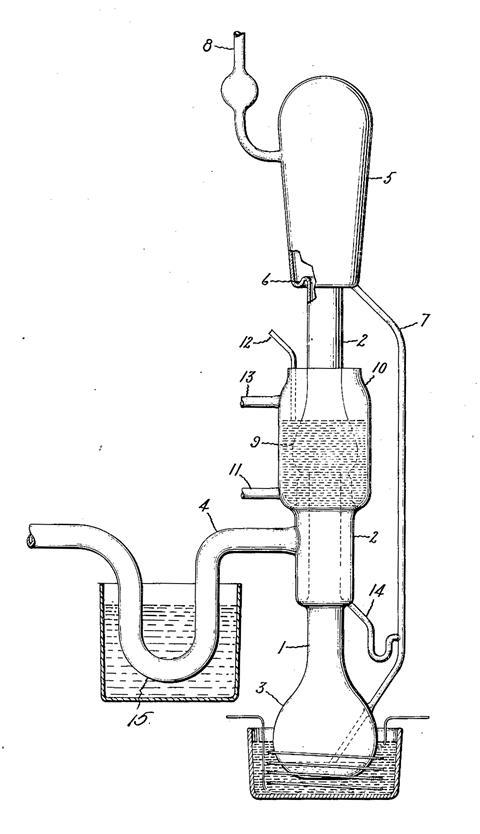

A few months after Gaede’s report, Langmuir published a pair of papers (accompanied simultaneously by a patent) describing new mercury vapour pumps ‘of extreme speed’. Like Gaede’s these devices had an element of magic about them, being pumps with no visible moving parts. A gale of mercury vapour, generated from a heated reservoir at the bottom of the pump, blasted upwards through a central tube and entrained gas drawn into the annular space surrounding the jet, from which it was removed by an additional backing pump. The walls surrounding the nozzle were water-cooled to condense the mercury; as a result little or none of the vapour could travel beyond this condenser. The liquid mercury simply trickled back down to the reservoir to be re-vapourised. Even at low pressures, the pumping speeds of this new device were unprecedented.

Despite the similarities, Langmuir emphasised that this pump was fundamentally different from Gaede’s; the cold walls of the mercury were responsible for the upward movement of the vapour. It was therefore a condensation pump, not a diffusion pump.

The theory behind the practical

The pressures were so low that Langmuir found that the McLeod gauges that had served everyone well up to this point for measuring low pressures were unable to cope. In response he began developing the theory of gas viscosity and invented two devices. The first was a gauge based on the oscillations of a long quartz fibre inside a tube attached to the vacuum manifold. Using a cathetometer (a small telescope) he could record the damping of the swinging fibre, from which he could infer the pressure.

A second, more sophisticated device consisted of two metal discs, one above the other. When the lower disk was spun at high speed by a small electric motor attached to its centre, the viscosity of the gas in the gap caused the upper disc, suspended from a torsion fibre, to twist by an angle. A small mirror allowed the angle to be measured. Langmuir’s pumps unleashed a torrent of studies both from Langmuir’s colleague at GE, Saul Dushman, who would become one of the leading authorities on high vacuum, and from chemists and physicists across the world, for whom atomic and molecular beam experiments became much easier.

Ultimately all of this work was in support of work to understand the filaments inside the bulbs and all of Langmuir’s work indicated to him that the forces that led to atoms binding to the surface were of exceptionally short range. While some like Manfred Eucken had proposed that there was a mysterious ‘action at a distance’ process involved, the unveiling of the structures of crystals by Lawrence and William Bragg using x-rays suggested to Langmuir that the adhesion of molecules to surfaces involved nothing more than chemistry.

Well aware of the rise of quantum theory, Langmuir began to speculate about chemical bonding, in many ways in parallel with Gilbert Lewis, but chose not to involve himself with the mathematical theory. Instead he embarked on a series of experiments to explore the forces between molecules. His work revealed the way in which molecules could organise themselves into what he called ‘monolayers’ on surfaces.

The elegance of his experiments and the breadth of the science he drew upon is breathtaking

Building on Agnes Pockels’ and Lord Rayleigh’s experiments with soaps on the surface of water, Langmuir developed a method where he could put precise volumes of different fatty acids and triglycerides, dissolved in alcohol, onto the surface of water and measure the area they covered. This led to the conclusion that the molecules were highly elongated and self-organised on the surface, with the polar head dipping into the water and the tails, whatever their length, sticking up in the air. By changing the temperature and the degree of confinement of the molecules on the surface he could demonstrate phase transitions for the films analogous to solid, liquid and gas, and to link the observed surface tension to the structure of the surface layer.

Layers of discovery

The elegance of his experiments and the breadth of the science he drew upon is breathtaking. He would extend this with his co-worker Katherine Blodgett. Together they showed how the layers could be transferred to glass or mica plates and further layers added one by one in what is today known as the Langmuir–Blodgett technique. Langmuir would be awarded the Nobel prize in chemistry in 1932 for having opened up surfaces for investigation, much of which he did without the aid of spectroscopy, x-rays and other tools; just patient and methodical observation.

Although the great financial crash of 1929 would result in a significant scaling back of the GE Research Laboratory, Whitney’s optimistic principle of letting researchers get on with basic research and have fun in the lab was widely copied across American and European industry. Langmuir and other industrial researchers were given time and space to explore their own ideas and then develop them into things that might eventually be taken to market. As companies have become ruled by professional managers and financial experts, the search for ‘shareholder value’ has led to many of the great labs being trimmed or even eliminated. Where would a young Irving Langmuir find as congenial, creative and optimistic an environment as he found in Schenectady?

References

I Langmuir, J. Franklin Inst., 1916, 182, 719 (DOI: 10.1016/S0016-0032(16)90056-5)

I Langmuir, Phys. Rev., 1916, 8, 48 (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRev.8.48)

I Langmuir, US patent US1393550, 1916

No comments yet