The UK government has agreed a £150 million support package for the Grangemouth industrial complex in Scotland. The site houses the UK’s last remaining ethylene production plant, following ExxonMobil’s decision in November to close the Fife Ethylene plant in nearby Mossmorran in early 2026, and Sabic’s decision earlier in the year not to re-start its Olefins 6 cracker in Wilton.

The deal includes £25 million investment from plant owner Ineos, £75 million in financing from NatWest bank (underwritten by the government) and £50 million in government grants, according to BBC reporting. Ineos has agreed assurances that the funding can only be used to improve the site (rather than subsidise its everyday running) and give the government rights to a share in future profits.

Even before this year’s closures, the UK imported over $1.5 million-worth of ethylene a year, predominantly from Czechia, according to World Bank trade data. Ineos has already closed the oil refinery on the Grangemouth site, choosing instead to ship shale gas-derived ethane from the US to feed its ethylene production. This means that all of the UK’s ethylene supplies now effectively rely, to some extent, on imports.

The UK’s plastics processors already consume around double the volume of plastics raw materials – including ethylene – produced domestically, with the shortfall coming from imports. At the same time, plastics products are one of the UK’s most significant exports, worth almost £12 billion in 2024. The economic significance of this industry is part of the reason why the government has stepped in to support Grangemouth.

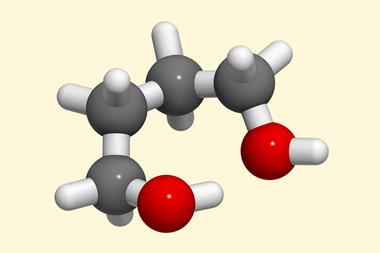

As Sky News economics editor Ed Conway points out, ethylene is a strategically important commodity, because it is the starting point for manufacturing all kinds of everyday items. Losing domestic ethylene supply would not only make the UK’s plastics industry more vulnerable to international influences, it could trigger a domino effect throughout the UK’s chemicals sector, threatening hundreds of thousands of jobs and critical industrial infrastructure.

However, it is far from clear how long the government’s investment will keep the wolves from Ineos’s door in Grangemouth. Optimistically, it is possible that the intended upgrades, combined with the government’s strategic promises to lower industrial energy costs and introduce carbon emissions taxation on imports could tip the balance back in favour of domestic industry. In the meantime, the situation will remain distinctly precarious.

Ed. This article was updated to correct an error in the UK ethylene imports figure.

No comments yet