Ben Feringa reveals the one activity that gets him out of the lab

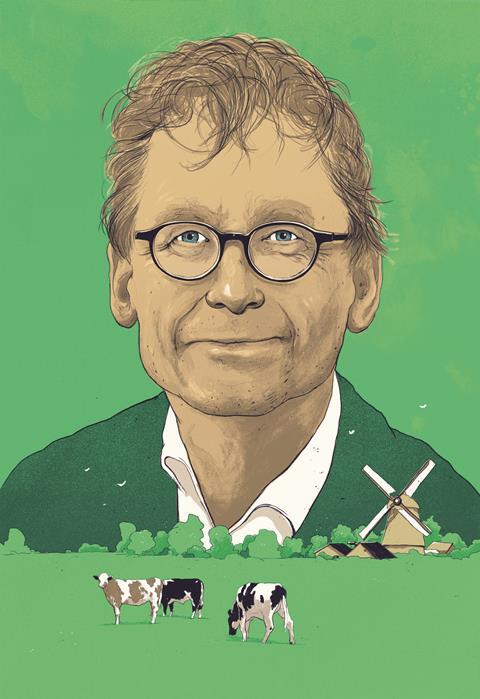

Ben Feringa shared the 2016 Nobel prize in chemistry for his work to develop molecular machines. Feringa is an organic chemistry professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and chairs Chemistry World’s editorial board.

I grew up on a farm in northeast Holland, the Netherlands, close to the German border. I wanted to be a farmer like my father, to follow in his footsteps, but he gave me wise advice to first study and then consider my options. In high school, I had an excellent chemistry teacher. I met him again recently when we had a reunion, he is well in his seventies now. He was great, he did experiments with us and I started to have a great love for chemistry that you can see and smell – you see beautiful crystals and colours.

I love chemistry because of its practical side – we find chemistry all around us. The fact that you could make things that have never existed before was also something that always gave me inspiration. I love the idea of learning from Mother Nature, but then going a step further because we are not limited by the molecules that nature uses.

I am really convinced that we have to reshape our chemical industry to make it way more sustainable, lower energy. The chemical industry uses a lot of energy. We need to think about more sustainable, cleaner processes and new catalytic processes, and also replace very precious catalysts with abundant materials, like moving from palladium to iron.

I always bike to work every day about 14.5km one way, so almost 30km total. That is good exercise – it keeps me fit and it clears my mind, to give me fresh ideas. Another of my hobbies is history. I like to learn from the past, and to see what our ancestors did – their dreams and what they accomplished.

I only close my lab for one reason – when there is ice on the lakes and the canals in the north of Holland! Ice skating is a passion of mine; when there is enough ice outside that you can skate from one village to another on the lakes, I go skating. You can’t disturb me, even with a new JACS paper or Chem comm paper.

Leonardo da Vinci is one of my heroes. He was not only an artist, he also came up with all of these other inventions. He was the first to design a submarine and he designed many weapons. My other hero is of course Jacobus van’t Hoff, the first Nobel laureate in chemistry. He got the Nobel Prize for the van’t Hoff laws and discovered, together with Le Bel, the picture of the tetrahedral model of carbon. He could have easily gotten a second Nobel Prize for that. From van’t Hoff we know that there are three dimensions to molecules, and we have mirror images.

I have three daughters and they are all keen sailors. I learned sailing from them. I do it for fun, my daughters are much better than I am – they are professionals.

The hardest thing I have ever done is snowboarding. Two of my daughters are very good snowboarders. I said, ‘OK, I can learn this’, but after a day I decided to just continue with skiing because snowboarding was very tough.

The biggest threat to science is those who think science is only an opinion. I hear this now, from politicians even. It is absolutely incredible when you hear this kind of talk and you realise that these people are saying this as they hold a smartphone in their hand to communicate. These smartphones didn’t exist 10 years ago, and the materials – the transistors and the liquid crystals – were discovered by physics and chemistry in the 1940s and 1950s. It took over 50 years to develop them, and now they have completely changed the world, including the world of those people who dismiss science. Where would we have been without science? Science is more important now than ever – to get new insights, to get new inventions, to address all of the problems that we face in society. We should value science and invest in science a lot, otherwise we might have a serious problem.

Please advocate scholarship and learning clearly, especially to young people. Give them a future – educate them and train them based on a scientific footing, and not on opinions or beliefs. We have had universities and scholarship in Europe for over a 1000 years; please let’s value that and make the right decisions for the future. Of course, we should be critical as scientists – critical about ourselves and critical about what we are doing – but that is part of the scientific attitude and the way you train your students. Teach young people to question, but also to use rationale and move forward.

No comments yet