Tracking down an obscure kit’s creator can make you hopping mad

Gail Nickerson and Sam Likens

American chemists (1938– and 1923–2006). Inventors of a hop oil extractor

People sometimes ask me where I get my ideas for this column. Some choices are obvious. Other ideas emerge from chance conversations or from the chase of something else. And then there’s social media, typically a picture captioned ‘what is this thing?’. Among the bits and bobs sent my way have been spiral gauges, isoteniscopes, osmometers of various design, bizarre stillheads and a plethora of curiously shaped flasks.

A few months ago, someone sent me a picture of a piece of glassware that completely stumped me. Resembling a cormorant drying its outstretched, but slightly unsymmetrical, wings, the device was some kind of weird distillation head, but with ground glass connections on both sides and in the wrong place. I was utterly baffled. After trying to be clever – using reverse image searches online was a total failure – someone rescued me by posting ‘it looks like the Nickerson–Likens device’. The what?

From cheese to durian fruit to hops, this is the kit that people use to isolate delicate volatiles before subjecting them to GC–MS. But how on earth does it work? I was rescued by a video posted by an academic in Spain. Even with my rather rudimentary Spanish, the subtlety and cunning of the device left me awestruck. The glassware made possible the simultaneous steam distillation and counter-current solvent extraction of infinitesimal quantities of natural products.

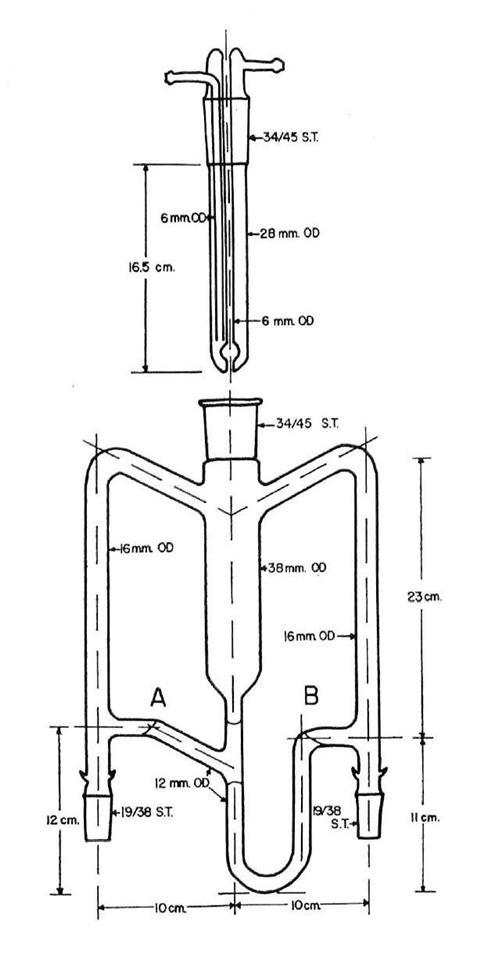

Imagine that you wanted to extract the bitter components of hops – the ‘alpha acids’, such as humulone and cohumulone – using steam and dichloromethane. The aqueous flask containing the hops is attached on the A side, while a small flask – a centrifuge tube, for example – containing dichloromethane is attached on the B side (see diagram, below). Steam is then passed through the A side while the dichloromethane is boiled on the other. The cold finger in the central body of the device acts a condenser for both phases, where the extraction takes place as the two condensate drip together into the tube below. By arranging the two return tubes asymmetrically, the aqueous phase at the top and dichloromethane at the bottom are returned to their respective flasks; the distillation/extraction can be conducted exhaustively to produce a concentrate in the organic phase ready for injection into a gas chromatograph. The real beauty of the device lies in its versatility. If one uses a less dense solvent, such as diethyl ether, one only has to reverse the attachment of the two flasks to achieve the same result.

The original paper included a detailed description of both its construction and operation. But who were Nickerson and Likens? Both had worked in the hops research team at the Oregon Agricultural Station in Corvallis, US. An internet search soon turned up a death notice for Sam Likens. But undergraduate yearbook photos and a recording of Gail Nickerson talking about her student days gave me hope that I might yet find her.

At first, Nickerson was elusive: the only trace was a cryptic listing that she had been made a Knight of the Order of the Hop at the International Hop Growers Congress in Strasbourg in 1994. Neither my malt specialist friend Dave Griggs, nor Martin Pavlovič of the Slovenian Institute of Hop Research and Brewing, could help me. Now utterly obsessed, I tried to track down former collaborators. Still nothing. By then, I had read several articles about the history of hop growing in the north west US, and the story of how systematic selective breeding by an Austrian geneticist, Al Haunold, had led to the creation of new varieties of hops for which the ‘alpha’ content in the hop oil exceeded 11% – nirvana for brewers and a gold mine for farmers. Eventually, I found Haunold’s children on Facebook who kindly introduced him to me. He, in turn, gave me Gail Nickerson’s email address.

Nickerson told me her story over the telephone. Having enrolled to study science at Oregon State University, she ‘flunked her exams’ and instead became a lab technician at the Oregon Agricultural Research Station, where Sam Likens was the boss. Likens, who had fought in the second world war, had benefited from the G.I. Bill that funded returning veterans to study at university. He had become a hop researcher, and it was he who hired Nickerson.

Initially, Nickerson washed glassware. Gradually, she went on packing gas chromatography columns, building a Craig counter-current extractor (Chemistry World, February 2011, p68) and carrying out experiments to quantify the components of hop oil. One day, Likens wondered whether it might be possible to extract the ‘hop aroma’ from beer itself – a fearsome challenge given concentrations in the part per billion range. It was this question that led to the invention of the device that combined distillation with extraction. Several prototypes were built by the in-house glassblower, Wade Meeker, before the final design was achieved. It worked like a charm. Of the two papers, it was the one that Nickerson wrote that got the most citations. Hop and aroma science would never be the same again.

Initially, Nickerson washed glassware. Gradually, she went on packing gas chromatography columns, building a Craig counter-current extractor and carrying out experiments to quantify the components of hop oil. One day, Likens wondered whether it might be possible to extract the ‘hop aroma’ from beer itself – a fearsome challenge given concentrations in the part per billion range. It was this question that led to the invention of the device that combined distillation with extraction. Several prototypes were built by the in-house glassblower, Wade Meeker, before the final design was achieved. It worked like a charm. Of the two papers, it was the one that Nickerson wrote that got the most citations. Hop and aroma science would never be the same again.

Nickerson would remain with the team for the rest of her career, continuing with analytical chemistry. She also became involved in genetic studies of the hop varieties and technical drawing for other scientists. And she got her BSc, a reminder that degrees and qualifications are, at best, proxies for ability and knowledge. For me, these deep dives into specialist chemical niches enrich my sense of wonder at human ingenuity. In a time of spin and disinformation, it is a healthy way to stay grounded in reality.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to everyone mentioned in the article for their enthusiastic help but especially to Gail Nickerson for her recollections.

References

S Likens, G Nickerson, Proc. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1964, 5

G Nickerson, S Likens, J. Chromat. 1966, 21, 1 (DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)91252-X)

No comments yet