The Chemists’ Community Fund – formerly the Benevolent Fund – has been helping people for 100 years. Rachel Brazil looks at how it works, now it may be more needed than ever before

Even before the full implications of the Covid-19 outbreak were being felt in Europe, Chemists’ Community Fund manager Anna Dearden had begun to reach out to members in south-east Asia. Now the pandemic is global, it’s clear that there will be serious long and short term impacts on many members. The Chemists’ Community Fund wants you to know it can help, whether you are a student, displaced from your halls of residence, or a self-employed member, experiencing a significant loss in income.

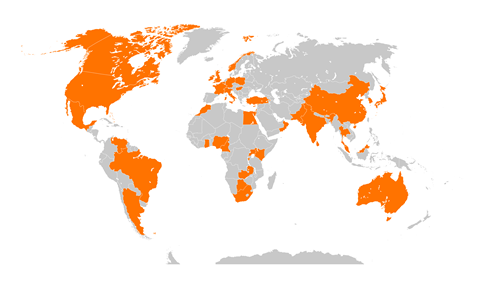

This may surprise those who imagine the fund only supports retired and disabled people, but that’s not the case. ‘We often pro-actively reach out to members around the world when there are disasters,’ explains Dearden. This includes hurricanes and floods, the 2019 terrorist attack in Sri Lanka, and the recent wildfires in Australia. During the 1990 Gulf War, the fund was able to provide support for an Iraqi member who was stranded in the UK, and more recently has supported members from Syria who needed to relocate.

The fund can often provide financial relief in as little as 48 hours

It has also supported those recovering from smaller scale disasters in the UK. When a fire destroyed part of the chemistry department at the University of St Andrews in 2019, the knock-on effects were felt most keenly by many PhD students who lost their work or were unable to continue it in St Andrews. ‘This was one of those reactive things that we’re able to do. We were able to help in terms of the personal costs that students were incurring when they needed to travel elsewhere for their studies,’ Dearden explains. ‘Rather than work with individual students, we actually worked with the university, enabling them to have a grant pot, which they could allocate. So, for example, they would know if someone needed to travel to another location for some specific equipment to analyse their sample.’

The fund has been able to help many chemists in crisis get back on their feet. ‘It’s not only the fact that we’re able to assist them, it’s the fact that we’re able to assist in a timely way,’ says Dearden. In an emergency, once the details are established and confirmed, the fund can often provide financial relief in as little as 48 hours.

- The Benevolent Fund was founded in 1920 as a memorial to fellows of the Institute of Chemistry who died in the first world war. Like many similar professional funds, it helped widows, children, the elderly and disabled.

- The fund’s first case supported a fellow who was out of work for several months with a young family to support. The support continued for many years, eventually helping his widow after his death.

- During the second world war, a member who broke his leg in an air-raid blackout received immediate support followed by a monthly sum of money.

The era of benevolence

As the fund approaches its centenary, our current crisis situation has some parallels to those that chemists may have experienced at that time. The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919, which killed 50 million worldwide, would still have been fresh in their minds, as well as the severe losses of the first world war (1914–18). There are mentions of charitable aid as early as the founding of the Institute of Chemistry (a precursor to the RSC) in 1877, but the Benevolent Fund, as it was called until 2016, was officially set up in 1920 as a memorial to fellows of the Institute who died in the first world war. An initial £251 was supplemented by an additional £300, raised by an inaugural appeal to the Institute’s 3000 members.

In 1946, 15 children were offered funding for a summer holiday

‘The early 20th century was the era of benevolent funds, particularly after the first world war when quite a few of the learned societies set up funds – this was pre-welfare state and pre-NHS,’ explains Dearden. Professions set up these funds to support widows, children, the elderly and infirmed. Before the state was willing to provide support and before occupational pensions became commonplace, these funds proved invaluable to those in need.

Historical records show the sort of support once provided for members and their dependants. For example, minutes from 1946 show 10 families being supported by the fund and a total of 15 children were to be offered funding for a summer holiday. In the 1920s, several unemployed members were given loans to allow them to relocate to the US to find employment. A passage to the US is not something that today’s fund would cover, explains Dearden. ‘But if someone needed to relocate today because they’re out of work, the fund might be able to assist with relocation costs and also with retraining grants.’

By the 1960s extreme poverty in the UK had been alleviated by the welfare state: the National Insurance Act of 1946 established a comprehensive system of social security, and the National Health Service was created in 1948. The fund continued its work for those falling through the cracks; that support includes visits from the fund’s volunteers. ‘We couldn’t reach as many members as we do with our team of four staff, so we have a small team of trained volunteers who often do visits to members on our behalf,’ says Dearden. ‘We currently have a volunteer visiting someone in a care home once a month just to maintain their interest in chemistry in [their] retirement.’ Chemists’ Community Fund volunteer Noel Grabham has been visiting members since the 1960s and says he has gained a lot of satisfaction from the experience. ‘You have to be a certain sort of person to do that sort of work,’ he says.

Financial support given by the Fund is allocated using a financial model based on the minimum income standard, as defined by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, an independent social change organisation with a long history of working to solve UK poverty. ‘We also currently do a lot of work benchmarking with other benevolent funds,’ says Dearden, who regularly interacts with managers of similar funds set up to support accountants, engineers and print-worker; ‘Like ourselves, they’ve needed to adapt what they provide to match the lives of their beneficiaries.’ The fund also takes care to research the level of support that is appropriate in all countries where RSC members are located, who may seek help.

- The introduction of social safety nets in the UK – such as the National Health Service and social security – meant extremes of poverty became more rare.

- In 2016, the Benevolent Fund became the Chemists’ Community Fund with an extension of its approach. It now provides support for any member or their family. It now helps those with caring responsibilities, or those with specialist support needs, attend events and conferences.

- After the 2019 fire at the St Andrews chemistry department, the fund helped many PhD students who had to travel elsewhere to complete their research.

Changing times, changing needs

In 2019 the fund spent almost £530,000 supporting chemists, a figure that has increased sharply over the last few years. The number of enquiries to the fund has also gone up four-fold and grant expenditure increased by 59% from 2018 to 2019. It’s possible this is in part a sign of today’s growing career insecurity, according to Kevin Gough, the fund’s grants committee vice-chair. ‘Over the last few years, more and more members are finding times harder.’ Staff have also been working hard to increase awareness of the fund among RSC members.

Rather than just supporting those at risk of extreme poverty, the fund is there for anyone in the chemistry community in need of help

More significantly there has been a change in the type of member seeking help. ‘There’s a surprising number of inquiries from people that are under the age of 50,’ says Gough. The average age of a member contacting the fund for the first time is 51, with the 31–40 age bracket being responsible for the largest number of enquires. 54% of enquiries come from those in employment compared to only 24% from those retired.

Julia Hatto, a trustee of the RSC and the Chemists’ Community Fund, agrees that there may be more need now. ‘40 years ago, when you graduated in chemistry and got a job in a big company, it felt like a job for life, but things [have] become a lot more unstable and uncertain.’ But as she explains, some of the needs aren’t necessarily monetary. ‘And that’s where the fund can help.’

In 2016, given the chemistry community’s evolving circumstances, the fund sought to take a more proactive approach: to not only relieve poverty, but also to prevent members and their families falling into it and help beneficiaries to become self-sufficient as soon as possible. ‘It might sound like a really small tweak, but it has enabled us to do so much more – now we can do more proactive work,’ says Dearden. The subtle change, backed up by advice from the Charity Commission to ensure the original trust’s deed was still being adhered to, was accompanied by a name change to the Chemists’ Community Fund, to try and create some distance from the old fashioned idea of who benevolent societies were for. Rather than just supporting those at risk of extreme poverty, the fund is there for anyone in the chemistry community in need of help. ‘And it’s not just members: it’s members’ dependants, spouses and partners,’ adds Gough. Past members who held over 10 years’ membership are also eligible for support in the same way.

‘[The fund] started thinking a bit more broadly about the kind of people that needed help,and what help would make a difference,’ says Hatto. The broadening of the remit has allowed for several new initiatives and different types of grants, one example being mobility grants for those who need specialist equipment to help with everyday tasks.

The fund were really helpful

When Cardiff University chemistry student Genevieve Ososki was diagnosed with a neurological disorder and became dependent on a wheelchair, she thought she would have to give up laboratory work and any chance of a future career in chemistry. But a grant from the fund in 2017 allowed her to purchase an electric sit-to-stand wheelchair, so she could continue to work safely in the lab.

She needed an electric wheelchair that could support her to a standing position, allowing her to work at bench-level. When she could not get funding through the NHS, the Chemists’ Community Fund stepped in. ‘The fund were really helpful,’ Ososki explained in an interview on the fund’s website. ‘They helped me with all of the application forms, they helped me get all of the information that they needed, all of the evidence that the committee would need in order to make a decision. And then once all of that evidence was together, they were really quick and responsive in getting back to me.’

The chair has given Ososki independence in her day-to-day activities and she went on to complete her degree and start a PhD in mesoporous photocatalytic films, also at Cardiff. ‘I have a promising career as a chemist ahead of me. It is something I had come to believe was an unachievable pipe dream, but is now a reality,’ Ososki said in the interview.

Another area of support now offered is re-training grants. ‘This could be somebody that’s had a career break, [been] a carer or on maternity leave and they need to go on a training course, to give them that ability to get back into work,’ explains Kim Sutton, one of the Fund’s three caseworkers who support applicants and beneficiaries.

There are also student hardship grants for those facing unexpected problems who cannot find support from their own universities. At the other end of the age spectrum, the fund introduced care-home top-up fee grants in 2019, for members with difficulties in covering the cost of residential care, who may otherwise be forced to move. Sutton says since joining the fund’s staff team in Cambridge she has dealt with a wider variety of cases than than she expected.

Signposting help

Part of the current broader role is also finding sources of help which will have the greatest positive impact for members in the long term. In 2019, 71% of calls resulted in staff providing information and signposting and in only 26% of cases was the support through direct financial grants. ‘We can provide a listening ear,’ says Sutton. ‘We usually call people back and chat through their problems and then maybe signpost them [to other organisations].’ The fund’s team can direct members to other organisations that provide access to counselling, well-being and bereavement services, as well as advice on legal and disability issues.

‘There’s an awful lot of extra support that the fund can offer. We’ve got links with groups like Cruse Bereavement Care, the National Autistic Society, Law Express,…if we think that it’s beneficial to somebody applying to the fund, we can actually put a referral through to any of those services,’ says Gough. There is a partnership with Citizens Advice Manchester so people can get support with benefit issues and similar problems; in 2019 the Fund spent just £720 on these referrals which led to recipients accessing over £13,000 in eligible benefits and income, as well as advice on housing.

In 2017, the fund launched workshops to tackle issues that many members will face. ‘The first two pilots were completely booked within the first hour of advertising to members, so we really knew it was an avenue we should be going down,’ says Sutton. 24 workshops were held in 2019, reaching 352 members. One workshop covers well-being and resilience – helping participants to understand when they or a colleague are struggling with well-being or mental health issues, and to be aware of the support tools available; the other looks at planning for retirement – covering both the financial and social aspects. They have additionally organised webinars on these issues to reach members further afield. In February 2019 the fund held a Brexit webinar to provide guidance for members from EU countries living in the UK.

The two week period 25 March to 7 April saw a five-fold increase in enquiries due to Covid-19

Sutton says they hope to expand the range of workshops they can provide over the coming years. ‘We’re looking at support for people with autism and dementia awareness. And menopause in the workplace is something that we’re thinking of planning [in the future].’

Hatto also hopes that in the future the Fund might even be able to assist the next generation of chemists by providing mentoring and practical support. ‘That’s quite hard because they’re not members yet, but I think that there is a way to [help] young people who find themselves in care, or in situations where they need help with finding a career path,’ she explains.

With the unprecedented Covid-19 crisis underway, it was clear that some members need direct and immediate help. Fund staff began reacting to the Covid-19 outbreak in February 2020, offering financial support to affected members in China and south-east Asia. This expanded in March to members in Italy, and ended with direct offers of aid to all members around the world, including more than thirty thousand in the UK and Ireland. As expected, the number of new enquiries rocketed: the two week period 25 March to 7 April saw a five-fold increase compared to same period in 2019. By mid-April, around £12,000 had already been granted to members in need due to Covid-19.

After a century of helping RSC members, the current pandemic shows that the Chemists’ Community Fund certainly still has a job to do. With the outlook uncertain to say the least, it is likely to become an even more crucial lifeline for chemists facing hardship. ‘More than ever now people need to realise they can reach out – even for something that seems fairly trivial to them. Because if you can act when something is quite small you can prevent something quite big happening,’ says Hatto. For all chemists, whatever the need, the message is to engage with the fund. ‘Members should know that the fund is more likely to support [them] than not, if there is a genuine case of need,’ says Dearden.

For Gough, working on the grant’s committee has confirmed what a difference the fund can make. ‘[There] are a few individual cases that stick out where we know we’ve been able to make a real impact on that person’s life. The emails and letters of thanks that the team gets and shares with the committee are the most fulfilling aspect of the whole thing.’

Rachel Brazil is a science writer based in London, UK

Additional information

The fund is seeking members to be involved in the committee or as volunteers; for more information please visit the fund’s website

Thanks to the RSC Library for their research into the early history of the fund. The Librarian is happy to help with historical research related to the archive and can be contacted via e-mail library@rsc.org

No comments yet