In a world that is racing ahead with new technologies, has the drug development process distanced itself from the patients it ultimately provides for?

How many times have you found yourself patiently waiting to see a healthcare professional, only to struggle to accurately describe your symptoms to them, or feel let down by the prescribed medication? Shifts in the pharma industry mean that these challenges and many others could be a thing of the past, with scores of emerging trends set to change the pharma industry as we know it.

The price of progressing a drug to market has climbed up to an impressive $1.8 billion (£1.3 billion) with around 40% of new drugs failing at phase II, when they are first tried in a patient. UK healthcare expense is approximately 9.9% of its GDP and in the US, it is over 16%. This leaves us with a problem: how do patients, governments, healthcare providers and insurance companies pay for novel drugs? The industry is undergoing a key shift from paying per drug to paying per outcome, and it is therefore more important than ever for pharmaceutical companies to prove that their new innovative drugs have added value over existing therapeutics.

The global challenges and costs associated with an ageing population, coupled with rates of chronic disease that are rising faster than GDP, mean that the pharma industry needs to overcome previously unseen digital and technological barriers. CatSci has taken a look at just a few of these; from data silos to general lack of patient representation in the early stages of drug development, and the new tech that is fighting back. When used effectively, the amazing innovations available to us can be used to enhance the human experience rather than take away from it – and in pharma this primarily comes in the form of transforming and humanising drug development.

The advent of wearables and the volume of patient data being produced presents endless opportunities, but what are we likely to see in the near future? By integrating advanced technologies into the everyday lives of healthcare providers and patients, the future of pharma starts with the patients.

How can we humanise the pharma industry?

Genetic screening at the doctor’s office

Take just one issue in pharma today: efficacy. Any prescribed drug can be inefficient in an individual due to various reasons – for example genetics or lack of diversity in patient sets. Essentially, there are gaps between the expected and real therapeutic response that need to be closed. A notable emerging field here is pharmacogenetics: the study of how genes affect an individual’s response to drugs. The US National Library of Medicine explains that many currently available drugs take a ‘one size fits all’ approach, however an individual’s genetics can influence whether a particular therapeutic will be beneficial, cause adverse side-effects, or be effective at all. Pharmacogenetics data is being used to design new clinical trial approaches that should result in much more efficient, targeted drugs. With more immediate effects, diagnostic test kits have been introduced. These kits enable the genetic screening of patients that can give their doctor more information about how they’re likely to interact with a drug, to help inform prescriptions and prognoses. As the field of pharmacogenetics grows, providing more genetic data, these kits will become even more useful in ensuring that patients, healthcare professionals and pharma companies all see the expected response.

Historically, drug companies have targeted blockbuster drugs and chronic diseases with large patient populations, without meeting the needs of smaller groups of patients

Personalised medicine, wearables and in-vivo monitoring

The days of reading the slip insert with your pill are numbered, in the future you should be provided with data around your pill and information about how it is specifically interacting within your body.

Genetic screening is just one tiny aspect of personalised medicine, a phrase that will mean many different things to many different people. One of the most exciting and futuristic applications weaves together digital technology and wearables. In 2015, the FDA approved the first digital medicine containing an ingestible sensor which could digitally record ingestion and provide data to healthcare professionals and caregivers. This method of in vivo monitoring using biosensors can measure how well patients follow a course of drugs; for example, by placing a radiofrequency emitter within a pill that activates on contact with stomach acid. An ingestible biosensor can then relay information to a server about when the pill is being absorbed. Another application is in dosage: many pharmaceuticals are dosed from phase III studies that are limited due to cost. No patient will experience exactly the same therapeutic response to a specific dose of the same compound, and this is down to more than just weight and other standard factors. There is precedence now for people to have in vivo monitors which can notify them when to take their medicine. As people become more tech-focused and the internet of things develops, this is likely to become much more commonplace and the data could help to inform optimised population doses.

With the rise of wearable fitness trackers, patients are becoming increasingly interested in the data they can receive about their own health. It’s been estimated that 245 million wearable devices will be sold in 2019. They’re already being actively exploited by healthcare insurance companies to incentivise a more active lifestyle. Devices that today count steps and active minutes could in the future also relay all kinds of information about when and how to take your prescriptions, how they are working in your body, and your prognosis.

Patients, big data and big patient data

For a truly futuristic drug development process, patients need to be treated as equal partners from discovery through to manufacture. Starting with the pharmaceutical company, patients and medical practitioners could be included on advisory boards so that they can convey their exact needs to the relevant professionals, and break down some of the barriers between big pharma and patients. Patient data is another significant influence on the industry, and we are generating lots of it. The FDA has relaxed their constraints on genetic screening service 23andme, which means that it is now much easier for patients and their doctors to access genetic information. This is just one source of huge amounts of patient data that is becoming available and, when combined with feedback from the patient (potentially through wearable technology), can all be used to advance drug development. Key issues in academia and industry are the length of time it takes to publish results, the negative results that are never published and positive results that aren’t as good as they seem. All these data are important, and issues with access ultimately lengthen the development process for other companies as mistakes are often repeated.

One of the issues with the drug development model is that you don’t get proof of concept until phase II, several years into the development process, representing a huge investment of time and money. A well-designed drug prototype that has the opportunity to see a novel therapeutic interact with real patients, and work with human receptors rather than animals as early as possible in the development process, would be a huge advantage. If therapeutics in development were delivered to the homes of patients, and monitored there throughout everyday life rather than having to be put into facilities at great cost, we might be able to streamline the process.

Collaboration is key

Historically, drug companies have targeted blockbuster drugs and chronic diseases with large patient populations, without meeting the needs of smaller groups of patients. As many of the blockbusters are coming off patent, big pharma is faced with a decision: to go into the generic market or try to develop new cures for challenging or rare diseases. Much of big pharma has been successful in the latter. Healthcare will always be a big proportion of GDP, but we must ensure that this is being used to meet the needs of the diverse population, with a shift to listening to patients, representing smaller patient sets, and working to deliver what they really need. Despite a dip in 2016, the number of drug approvals in the past few years has shot back up to about 40 a year, thanks to better innovation and better understanding of the drug discovery and development process.

We see big pharma buying companies as early as phase I and licensing out their products to fund them through the clinical development journey

The drug innovation engine is now being driven by emerging pharma and for them to succeed, collaboration is key. The downsize of big pharma and investment coming in from venture capitalists, research councils and government means there is lots of seed funding available for scientists from academia and SMEs to innovate and discover new drugs. The talent pool exists, and now the funding is available to feed this innovation. Collaboration really comes in to play for virtual biotech companies – those that completely outsource their scientific development. Their outsourcing model means they can be very fast-moving, versatile and selective with their partners. Partnerships add great value as it allows them to work with other organisations, such as contract development/manufacturing organisations (CMO/CDMOs) and contract research organisations (CROs), that are highly skilled in many areas – such as chemical synthesis, rheology, screening or any other services they require.

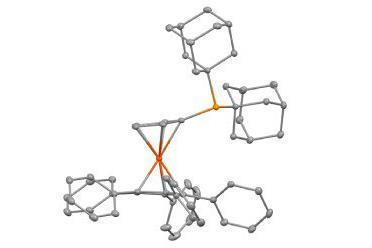

For example, as a chemical process research and development CRO, CatSci works with emerging pharma and virtual biotechs seeking to outsource their process development activities, from route design through to optimisation of the manufacturing process. By outsourcing to highly focused, flexible companies with expertise in a specific area, these emerging pharma companies are able to make sure that each stage of their process is as streamlined as possible, allowing them to focus on the other vital aspects of the process, of which there are many.

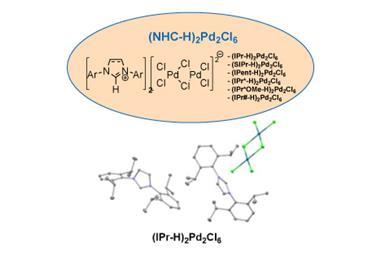

In 2016, approximately 70% of all assets in the clinic were from emerging pharma. The shift away from big pharma is driven by the new technologies being investigated, away from the traditional biologics and small molecules. Examples include using genome-editing, Crispr engineering, or T-cell lymphocyte technology to fight cancer, or working towards phenotype screening rather than a single target approach. Emerging pharma companies are also combining chemistry expertise with computing science; for example, AI, supercomputing power and systems biology among others. These novel technologies allow them to increase the probability that a specific asset will be efficacious in the patient. In order to stay relevant, any CRO, CMO or CDMO must in turn be able to provide the expertise and diversity to cater to these innovative processes. Then we see big pharma with capital buying these companies as early as phase I and licensing out their products to fund them through the clinical development journey.

Any small or virtual biotech needs to make sure that the process development and supply of their drug substance is not the rate-limiting step. In order to truly focus on maximising the value of your asset with the funds available, you need to select the right preclinical tests, think about clinical expenditure, and much more. Working with trusted suppliers allows you to focus more on the application of it.

To the future

It will be fascinating to see what percentage of new therapeutics in the future are those discovered by emerging companies. The focus is really shifting to high value products and services, collaboration, and humanising drug development – starting with the patient, using real patient data to inform good decision making.

With the combination of new drug discovery platforms and industry-changing technologies, it’s impossible to predict what healthcare might look like in 10, 20 or 50 years. Perhaps one day, your fitness tracker will relay information to your GP who can send you an e-prescription without needing to book an appointment. Perhaps even further down the line, you’ll be able to 3D print your completely personalised pill at home, and then that same fitness tracker will notify you when it’s time to take it, when it’s working, and when it’s time to take the next one! The only thing we can be certain of is that emerging trends and biotech companies are disrupting innovation as we know it, and the face of healthcare is evolving faster than we could imagine.

Ross Burn is the chief executive of CatSci

No comments yet