Researchers have used AI as a ‘creative architect’ to design muscle-inspired proteins that are stronger and more thermally stable than their natural counterparts. The approach could enable the design of superstable synthetic proteins that can survive in extreme environments where natural proteins fail – useful for biomedical materials, sensors or catalysts.

Most natural proteins are fragile, degrading at high temperatures, in harsh solvents or under mechanical stress. Previous efforts to improve protein stability have usually involved tweaking the DNA machinery that makes them with point mutations or by stabilising natural scaffolds. However, improvements have remained limited.

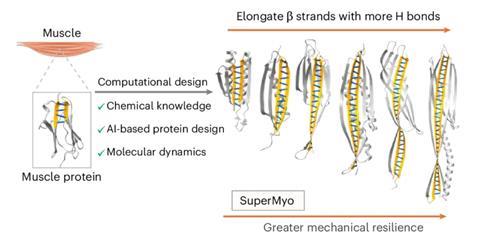

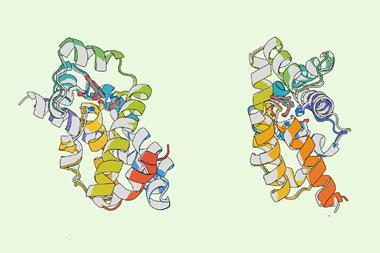

Now, a team led by Peng Zheng at Nanjing University, China, has turned to AI to design new protein structures from scratch with stability as the primary goal. Taking inspiration from naturally strong and stretchy muscle tissue, including the protein titin, which comprises a structural backbone of beta-sheets reinforced by dense hydrogen bonds, the team set out to develop an AI-driven framework that could maximise the hydrogen-bond network to make even stronger proteins.

‘The goal was to move beyond mimicking natural proteins to actively design superior, non-natural variants with tailor-made stability,’ says Zheng. ‘This allows us to directly “program” stability into the protein’s architecture, achieving performance that far surpasses most known natural or engineered proteins.’

To do this, the researchers trained an AI model on known protein structures as a way for it to understand how beta-sheets form. Then, the team instructed the AI to design new protein folds where beta-strands within the sheets are extended and aligned. This meant the possible number of hydrogen bonds between strands could be maximised. The upshot was that the AI could generate blueprints for proteins with more and better-organised hydrogen bonds than seen in natural proteins, increasing the number of backbone hydrogen bonds from four to 33. Computer simulations and lab experiments were then used to test the new proteins’ stability.

‘We were surprised by how linearly the mechanical strength increased with the number of hydrogen bonds in our designs,’ says Zheng. The top-performing protein, called SuperMyo, was shown to be more than four times stronger than the natural muscle protein it was inspired by. ‘Seeing such a dramatic leap in performance from a computationally designed protein was a thrilling moment.’

The team also created a hydrogel using the SuperMyo protein to test its robustness to extreme conditions. Experiments showed it retained its mechanical properties after being repeatedly heated to 121°C – a standard for autoclave sterilisation – and then frozen with liquid nitrogen, as well as being heated to 150°C for one hour. Conventional protein hydrogels usually completely break down at such extremes, says Zheng.

‘This opens doors to biomedical devices that can be sterilised, biocatalysis in harsh manufacturing environments and durable biomaterials for extreme environments,’ explains Zheng. ‘We envision a future where scientists and engineers can use AI-driven platforms like ours to design “protein parts” for specific challenging applications, whether in medicine, manufacturing or material science.’

‘Studies like this show there are many new emergent properties from designer proteins that remain unexplored and can now be achieved when we have powerful AI tools to democratise the process,’ says Possu Huang, a computational protein bioengineer at Stanford University, US. ‘I expect that there will be more studies in the coming years that will explore advanced material designs that are inspired by nature but extended beyond solutions offered by evolution.’

‘I find this very interesting work and a nice demonstration of how “mature” and widely usable protein design has become in the last few years,’ comments Max Fürst who investigates computational protein design at the University of Groningen, Netherlands. ‘This application of protein design is an excellent showcase of how structural biology AI models are now being integrated into all kinds of fields, from drug design to material sciences.’

References

B Zheng et al, Nat. Chem., 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-025-01998-3

No comments yet