An analysis of over 41 million research papers from the past 40 years has revealed that researchers who use artificial intelligence (AI) tools in their work publish more papers and receive more citations. However, using these tools may narrow academics research to those areas that are richest in data.

AI tools can help scientists identify patterns in large datasets, automate certain processes for high-throughput experiments or help with scientific writing. A team led by James Evans at the University of Chicago in the US, along with researchers in China, has sought to better understand how adopting such tools affects both individual scientists and the wider scientific community.

What do we mean when we say AI?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an umbrella term often incorrectly used to encompass a variety of connected but simpler processes.

AI is the ability of machines and computer programmes to perform tasks that typically only humans could do, such as reasoning, responding to feedback and decision making.

Generative AI is a newer variant of AI that analyses and detects patterns in training datasets to generate original text, images and videos in response to requests from users. ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, Google Gemini and more recently X’s Grok are all examples of chatbots that use generative AI.

Neural networks are an interconnected array of artificial neurons, akin to biological brains, that identify, analyse and learn from statistical patterns in data.

Machine learning is a subset of AI that allows machines to learn from datasets and make predictions based on new data, without programmers explicitly asking it to do so. Machine learning models improve their performance as they receive more data.

Deep learning is an enhanced type of machine learning that uses neural networks with many layers to analyse complex data from very large datasets. Applications of deep learning include speech recognition, image generation and translation.

Large language models or LLMs are a type of deep learning trained on large amounts of data to understand and generate language. LLMs learn patterns in text by predicting the next word in the sequence and these models are now able to write prose, analyse text from the internet and hold dialogues with users.

To do this, the team used a large language model to analyse over 41 million research papers, published over the past 40 years, that used AI tools. The model identified papers that used AI tools and split such studies into three AI ‘eras’: traditional machine learning (1980–2014), deep learning (2015–2022) and generative AI (2023 to the present).

Studies were analysed from across the natural sciences, including biology, medicine, chemistry, physics, materials science and geology. Evans explains that the team did not choose fields like mathematics, computer science and social sciences as they often describe development or use of AI tools, rather than using such tools to do scientific research. Human expertise was then used to evaluate a sample of papers classified by the model and they agreed with its choices in nearly 90% of cases.

Analysis revealed that the share of papers published using AI tools has rapidly increased over the past four decades, as has the number of researchers taking advantage of them, likely the result of such tools becoming more easily accessible. This result was consistent across all three AI eras.

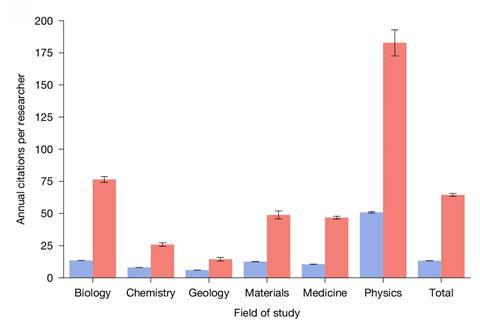

Additionally, scientists using AI in their research published around three times more papers and received just under five times more citations, on average, compared with those not adopting AI.

However, Milad Abolhasani, who researches autonomous flow chemistry at North Carolina State University in the US, suggests that the model may miss certain papers if the use of AI is not clear, leading to an undercount of AI-adopting studies.

Evans and his team also extracted the career paths of over 2 million scientists from the dataset, classifying them as either junior, who had not yet led a research project, or established. Teams that adopted AI tools were smaller with fewer junior researchers, yet early-career members in these groups were 13% more likely to stay in academia. Such AI-adopting junior researchers also tended to become established researchers around one-and-a-half years quicker than their peers.

However, the team was unable to fully explain why adopting AI tools increased scientific impact. Molly Crockett, a neuroscientist at Princeton University, cautions that the researchers’ definition of ‘impact’ is based on citation count and requires scientists to reach the level of principal investigator. ‘These metrics could equally reflect the hype and economic incentives to use a novel technology, aside from the quality of research, and the data cannot disentangle these explanations,’ Crockett adds.

The wider scientific community

While adopting AI tools can help individual scientists, further analysis suggested that using AI tools can contract research focus onto niche problems within already established fields. Areas with an abundance of available data are more amenable to research using AI, compared with fields that explore fundamental questions, such as the origin of natural phenomena. ‘Entire research areas may be at risk of extinction if they are not tractable for tracking with automation,’ says Crockett.

Results from the study also revealed that AI research leads to 22% less engagement between scientists, which can create ‘lonely crowds’ in popular scientific research fields.

‘We’re bringing these [artificial] intelligences into our research, but really only applying them on one part of the knowledge intelligence spectrum,’ says Evans. He thinks that this creates an imbalance between focusing on existing research problems, rather than exploring new ones. ‘The problem is that there’s a conflict between individual and collective incentive,’ he explains.

However, Abolhasani says that the results from this study doesn’t mean that scientists must use AI to have career progression. He adds that this study ‘should not encourage scientists to replace their critical thinking with a large language model’.

References

Q Hao et al, Nature, 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09922-y

No comments yet